What are lymph nodes?

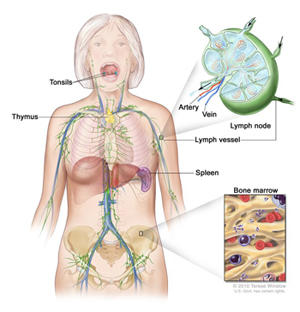

Lymph nodes are small round organs that are part of the body’s lymphatic system. The lymphatic system is a part of the immune system. It consists of a network of vessels and organs that contains lymph, a clear fluid that carries infection-fighting white blood cells as well as fluid and waste products from the body’s cells and tissues. In a person with cancer, lymph can also carry cancer cells that have broken off from the main tumor.

Lymph is filtered through lymph nodes, which are found widely throughout the body and are connected to one another by lymph vessels. Groups of lymph nodes are located in the neck, underarms, chest, abdomen, and groin. The lymph nodes contain white blood cells (B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes) and other types of immune system cells. Lymph nodes trap bacteria and viruses, as well as some damaged and abnormal cells, helping the immune system fight disease.

Many types of cancer spread through the lymphatic system, and one of the earliest sites of spread for these cancers is nearby lymph nodes.

What is a sentinel lymph node?

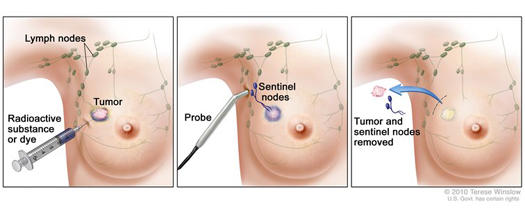

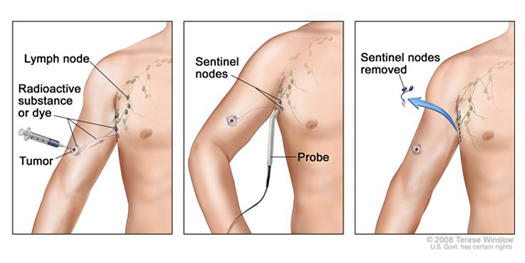

A sentinel lymph node is defined as the first lymph node to which cancer cells are most likely to spread from a primary tumor. Sometimes, there can be more than one sentinel lymph node.

What is a sentinel lymph node biopsy?

A sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is a procedure in which the sentinel lymph node is identified, removed, and examined to determine whether cancer cells are present. It is used in people who have already been diagnosed with cancer.

A negative SLNB result suggests that cancer has not yet spread to nearby lymph nodes or other organs.

A positive SLNB result indicates that cancer is present in the sentinel lymph node and that it may have spread to other nearby lymph nodes (called regional lymph nodes) and, possibly, other organs. This information can help a doctor determine the stage of the cancer (extent of the disease within the body) and develop an appropriate treatment plan.

What happens during an SLNB?

First, the sentinel lymph node (or nodes) must be located. To do so, a surgeon injects a radioactive substance, a blue dye, or both near the tumor. The surgeon then uses a device to detect lymph nodes that contain the radioactive substance or looks for lymph nodes that are stained with the blue dye. Once the sentinel lymph node is located, the surgeon makes a small incision in the overlying skin and removes the node.

The sentinel node is then checked for the presence of cancer cells by a pathologist. If cancer is found, the surgeon may remove additional lymph nodes, either during the same biopsy procedure or during a follow-up surgical procedure. SLNB may be done on an outpatient basis or may require a short stay in the hospital.

SLNB is usually done at the same time the primary tumor is removed. In some cases the procedure can also be done before or even after (depending on how much the lymphatic vessels have been disrupted) removal of the tumor.

What are the benefits of SLNB?

SNLB helps doctors stage cancers and estimate the risk that tumor cells have developed the ability to spread to other parts of the body. If the sentinel node is negative for cancer, a patient may be able to avoid more extensive lymph node surgery, reducing the potential complications associated with having many lymph nodes removed.

What are the possible harms of SLNB?

All surgery to remove lymph nodes, including SLNB, can have harmful side effects, although removal of fewer lymph nodes is usually associated with fewer side effects, particularly serious ones such as lymphedema. The potential side effects include:

- Lymphedema, or tissue swelling. During lymph node surgery, lymph vessels leading to and from the sentinel node or group of nodes are cut. This disrupts the normal flow of lymph through the affected area, which may lead to an abnormal buildup of lymph fluid that can cause swelling. Lymphedema may cause pain or discomfort in the affected area, and the overlying skin may become thickened or hard.

The risk of lymphedema increases with the number of lymph nodes removed. There is less risk with the removal of only the sentinel lymph node. In the case of extensive lymph node removal in an armpit or groin, the swelling may affect an entire arm or leg. In addition, there is an increased risk of infection in the affected area or limb. Very rarely, chronic lymphedema due to extensive lymph node removal may cause a cancer of the lymphatic vessels called lymphangiosarcoma. - Seroma, or a mass or lump caused by the buildup of lymph fluid at the site of the surgery

- Numbness, tingling, swelling, bruising, or pain at the site of the surgery, and an increased risk of infection

- Difficulty moving the affected body part

- Skin or allergic reactions to the blue dye used in SNLB

- A false-negative biopsy result—that is, cancer cells are not seen in the sentinel lymph node even though they have already spread to regional lymph nodes or other parts of the body. A false-negative biopsy result gives the patient and the doctor a false sense of security about the extent of cancer in the patient’s body.

Is SLNB used to help stage all types of cancer?

No. SLNB is most commonly used to help stage breast cancer and melanoma. It is sometimes used to stage penile cancer (1) and endometrial cancer (2). However, it is being studied with other cancer types, including vulvar and cervical cancers (3), and colorectal, gastric, esophageal, head and neck, thyroid, and non-small cell lung cancers (4).

What has research shown about the use of SLNB in breast cancer?

Breast cancer cells are most likely to spread first to lymph nodes located in the axilla, or armpit area, next to the affected breast. However, in breast cancers close to the center of the chest (near the breastbone), cancer cells may spread first to lymph nodes inside the chest (under the breastbone, called internal mammary nodes) before they can be detected in the axilla.

The number of lymph nodes in the axilla varies from person to person; the usual range is between 20 and 40. Historically, all of these axillary lymph nodes were removed (in an operation called axillary lymph node dissection, or ALND) in women diagnosed with breast cancer. This was done for two reasons: to help stage the breast cancer and to help prevent a regional recurrence of the disease. (Regional recurrence of breast cancer occurs when breast cancer cells that have migrated to nearby lymph nodes give rise to a new tumor.)

However, because removing multiple lymph nodes at the same time increases the risk of harmful side effects, clinical trials were launched to investigate whether just the sentinel lymph nodes could be removed. Two NCI-sponsored randomized phase 3 clinical trials have shown that SLNB without ALND is sufficient for staging breast cancer and for preventing regional recurrence in women who have no clinical signs of axillary lymph node metastasis, such as a lump or swelling in the armpit that may cause discomfort, and who are treated with surgery, adjuvant systemic therapy, and radiation therapy.

In one trial, involving 5,611 women, researchers randomly assigned participants to receive just SLNB, or SLNB plus ALND, after surgery (5). Those women in the two groups whose sentinel lymph node(s) were negative for cancer (a total of 3,989 women) were then followed for an average of 8 years. The researchers found no differences in overall survival or disease-free survival between the two groups of women.

The other trial included 891 women with tumors up to 5 cm in the breast and one or two positive sentinel lymph nodes. Patients were randomly assigned to receive SLNB only or to receive ALND after SLNB (6). All of the women were treated with lumpectomy, and most also received adjuvant systemic therapy and external-beam radiation therapy to the affected breast. After extended follow-up, the two groups of women had similar 10-year overall survival, disease-free survival, and regional recurrence rates (7).

What has research shown about the use of SLNB in melanoma?

Research indicates that patients with melanoma who have undergone SLNB and whose sentinel lymph node is found to be negative for cancer and who have no clinical signs that cancer has spread to other lymph nodes can be spared more extensive lymph node surgery at the time of primary tumor removal. A meta-analysis of 71 studies with data from 25,240 patients found that the risk of regional lymph node recurrence in patients with a negative SLNB was 5% or less (8).

Findings from the Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial II (MSLT-II) also confirmed the safety of SLNB in people with melanoma with positive sentinel lymph nodes and no clinical evidence of other lymph node involvement. This large randomized phase 3 clinical trial, which included more than 1,900 patients, compared the potential therapeutic benefit of SLNB plus the immediate removal of the remaining regional lymph nodes (called completion lymph node dissection, or CLND) with SNLB plus active surveillance, which included regular ultrasound examination of the remaining regional lymph nodes and treatment with CLND if signs of additional lymph node metastasis were detected.

After a median follow-up of 43 months, patients who had undergone immediate CLND did not have better melanoma-specific survival than those who had undergone SLNB with CLND only if signs of additional lymph node metastasis appear (86% of participants in both groups had not died from melanoma at 3 years) (9).