Toripalimab Becomes First Immunotherapy Drug Approved for Nasopharyngeal Cancer

, by Elia Ben-Ari

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the first immunotherapy drug for the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), a type of head and neck cancer.

The approval of toripalimab (Loqtorzi), announced on October 27, was based on results of two clinical trials conducted in Asia, where NPC is much more common than in most other parts of the world. Both trials were sponsored by Shanghai Junshi Biosciences, which developed the drug.

FDA’s approval of the drug—the first approval of toripalimab in the United States—covers its use as an initial treatment for people with NPC that has come back (recurred) or spread to other parts of the body (metastatic). The approval also includes using toripalimab on its own for people with recurrent or metastatic NPC that has gotten worse on or after standard chemotherapy.

The approval should immediately change the way that people with NPC are treated in this country, said Barbara Burtness, M.D., a head and neck cancer expert at Yale University who was not involved in the study.

In one trial, people with recurrent or metastatic NPC were randomly assigned to receive standard chemotherapy with or without toripalimab. Patients treated with toripalimab and chemotherapy lived longer overall and lived longer without their cancer getting worse (progression-free survival) than those who received chemotherapy alone.

In a smaller early-stage trial, researchers found that treatment with toripalimab alone shrank tumors or kept them from growing in some people with advanced NPC that had gotten worse despite previous treatment with standard chemotherapy.

“Chemotherapy has … been the mainstay of treatment for people with more advanced NPC,” said head and neck cancer specialist Tanguy Seiwert, M.D., of Johns Hopkins University, who also was not involved in the study. “This approval gives us an additional tool” for treating the disease.

“I am thrilled” that toripalimab has been approved for use in the United States, Dr. Seiwert added.

Differences between NPC and other head and neck cancers

NPC differs from other types of head and neck cancer in several ways, including its causes and the way it is treated. As a result, “patients with NPC are typically not included in clinical trials of head and neck cancer,” researchers wrote in their report of the trial of toripalimab plus chemotherapy.

Most cases of NPC are caused by infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Although most people in the world have been exposed to EBV, few develop NPC because additional risk factors play a role in whether cancer will develop.

These risk factors include genetics and environmental factors such as drinking alcohol and smoking. As a result, NPC is much more common in certain parts of the world, including southern China and Southeast Asia, than in the United States and some other parts of the world, Dr. Seiwert explained. There are also clusters of NPC in the Arctic and parts of the Middle East and North Africa.

If NPC is caught early enough, radiation and chemotherapy can often cure it, Dr. Seiwert said.

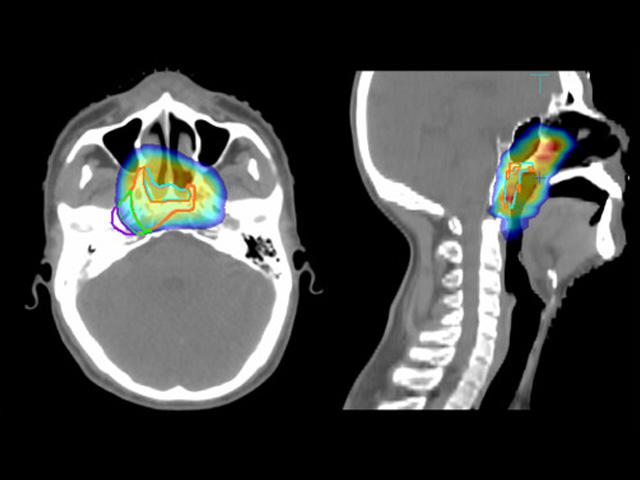

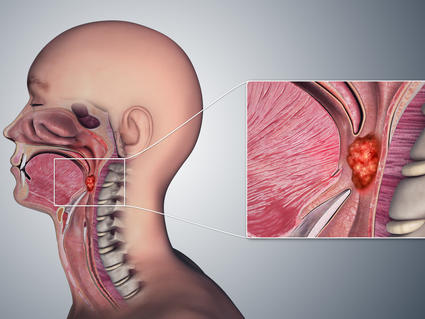

Unlike for other types of head and neck cancer, “surgery is not a good option for NPC because of its location in the skull, right behind the nose, where there are a lot of important structures,” he explained.

If NPC is diagnosed after it has already spread, or if it comes back after initial treatment, patients typically receive chemotherapy regimens that include cisplatin or other platinum drugs. Once the cancer has progressed after chemotherapy, there is no standard treatment.

Toripalimab is a type of immunotherapy called an immune checkpoint inhibitor. It targets a protein called PD-1 on certain immune cells, allowing them to better attack and kill cancer cells.

The first trial results showing that adding toripalimab to chemotherapy was more effective than chemotherapy alone were published in August 2021. Not long after, because toripalimab was not yet approved for use in the United States, treatment guidelines from leading US cancer groups began including the option of using other immune checkpoint inhibitors that target PD-1, including pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo), Dr. Burtness explained.

But rigorous clinical trials of those drugs have not been done in people with NPC, so they are not approved by FDA for that use.

“Now, we can use the right drug, which has been shown to provide clear improvement for patients in a large, randomized study, which is considered the highest level of evidence” that a treatment works, Dr. Seiwert said.

“It is wonderful to see something that extends survival for these patients,” Dr. Burtness said.

US toripalimab approval based on two clinical trials

The early-phase clinical trial that tested toripalimab alone in people with advanced NPC, called POLARIS-02, was conducted in hospitals in China. The trial enrolled 172 people with advanced NPC that had spread or gotten worse following treatment with chemotherapy.

In this trial, toripalimab, which is given as an infusion, shrank tumors in 21% of patients. The median length of time that people's tumors continued to respond without the cancer growing or spreading was almost 15 months.

The other trial, called JUPITER-02 and conducted in China, Taiwan, and Singapore, enrolled 289 people with recurrent or metastatic NPC who had not yet received chemotherapy for their recurrent or metastatic disease.

People in the toripalimab group received the drug along with chemotherapy for up to 6 months, followed by toripalimab alone as maintenance therapy until their cancer began to get worse. Those in the other group received chemotherapy for up to 6 months followed by placebo infusions.

Initial results from JUPITER-02 showed that people treated with toripalimab and chemotherapy lived for a median of 11.7 months without their cancer getting worse, compared with 8.0 months for those treated with chemotherapy only.

In addition, final results from JUPITER-02, which were reported November 28 in JAMA and represented a median follow up of 36 months, showed that toripalimab extended overall survival as well as progression-free survival.

Two years after starting treatment, 78% of people in the toripalimab group were still alive, versus 65% in the chemotherapy-alone group. After 3 years, overall survival rates in the two groups were 64% and 49%, respectively.

Patients in the toripalimab group also had substantially better progression-free survival: a median of 21.4 months versus 8.2 months.

More side effects with toripalimab

In JUPITER-02, the overall rate of severe side effects, including low blood cell counts, was similar in the two groups. The most common side effects, including severe ones, were due mainly to chemotherapy.

Immune-related side effects, including inflammation of the lungs and colon, abnormal liver function, skin reactions, and hormone problems such as an underactive thyroid, were seen with toripalimab.

Side effects that were seen more often in the toripalimab group included an underactive thyroid, upper respiratory tract infections, and pneumonia.

Despite the heightened risk of immune-related side effects with toripalimab, immunotherapy “is generally well tolerated” by patients, Dr. Seiwert said.

One cautionary note, Dr. Burtness said, is that “as with any immune checkpoint inhibitor, patients who have underlying autoimmune disorders can expect to have a higher risk” of immune-related side effects, including severe effects. In these patients, doctors may suggest starting with chemotherapy and then switching to toripalimab when the chemotherapy isn’t working anymore, she said.

Dr. Seiwert also noted that at least two more large, rigorous clinical trials of other PD-1−targeting immune checkpoint inhibitors that are not available in the United States have shown improved progression-free survival for people with advanced NPC when the drugs are added to chemotherapy.

But FDA’s approval of toripalimab as the first immune checkpoint inhibitor for treating NPC, he concluded, “is a true step forward.”