Mantle Cell Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Incidence

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is a less common type of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). With about 4,000 new cases each year,[1] MCL accounts for about 5% of all NHLs in the United States. The median age at diagnosis is approximately 65 years, with most cases occurring in men.

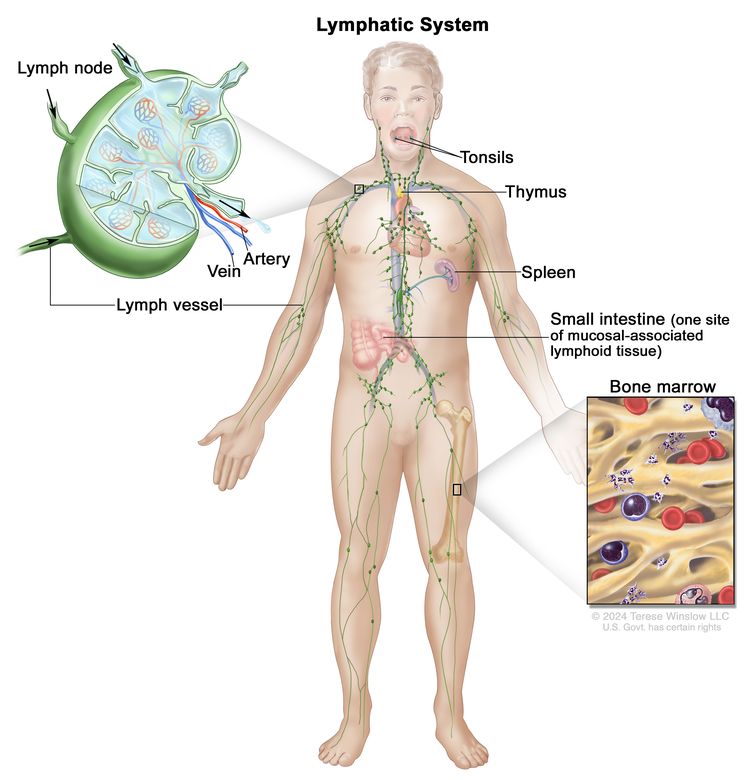

Anatomy

NHL usually originates in lymphoid tissues.

Clinical Features

MCL presents in the lymph nodes, spleen, bone marrow, and sometimes as gastrointestinal polyposis (especially in the colon).[1] Most patients with MCL have stage III or IV disease at diagnosis. Like low-grade lymphomas, MCL is highly responsive to treatment, but not curable in most cases. MCL is characterized by CD5- and CD20-positive B cells derived from the mantle region of the lymphoid follicle, most often with a translocation of chromosomes 11 and 14 (t(11;14)(q13;q32)), resulting in overexpression of cyclin D1.[2] Histopathology typically shows CD5-positive, CD20-positive, cyclin D1-positive, CD10-negative, and CD23-negative or low disease. More than 95% of cases are cyclin D1-positive MCL with a classic IGH::CCND1 fusion.[3] Rarely, the free kappa (chromosome 2) or free lambda (chromosome 22) enhancer may partner with CCND1, and other times CCND2, CCND3, or CCNE may be the rearrangement partner.

MCL may be divided into two clinical subtypes: indolent (often a non-nodal leukemic version) and aggressive (a nodal version).[2]

Indolent MCL

The more indolent version occurs in 20% of patients with MCL and is also called indolent non-nodal leukemia. Indolent MCL characteristics include:[2]

- Small (<3 cm) lymph nodes.

- Leukemic presentation.

- Early stage.

- Lack of constitutional B symptoms (fever, recurrent night sweats, or weight loss).

- Negative or low (<10%) SOX11 expression.

- Hypermutation of IGHV.

- CD23 and CD20 positivity.

- Absence of ATM or CCND1 variants or deletions.

Isolated gastrointestinal polyposis also has an indolent course. These patients have a significantly better prognosis (with a median survival exceeding 15 years), and many can defer therapy on initial presentation and be followed with a watchful waiting approach (as is done with other indolent lymphomas, such as follicular lymphoma).[4-6]

Aggressive MCL

Most patients with MCL (80%) present with more aggressive disease, which is also called aggressive nodal leukemia. Patients have a median survival exceeding 8 to 10 years. Aggressive MCL characteristics include:[2,7]

- Extensive enlarged lymph nodes.

- Rapid progression.

- Constitutional B symptoms.

- High (≥10%) SOX11 expression.

- Unmutated IGHV.

- CCND1 or ATM variants or deletions, or other genomic complexity.

Patients with a worse prognosis (median survival, 4 to 7 years) can be identified by the presence of blastoid or pleomorphic variants by microscopy, a high Ki-67 (≥30%), and TP53 variants or deletions.[2,3,8-11] Age and comorbidities may impact the prognosis and treatment options for any patient with aggressive MCL. Any patient with indolent or moderately aggressive MCL may later convert to a blastoid or TP53 variant/deletion phenotype, which is resistant to treatment due to genomic instability or selection of resistant clones through destruction of the predominant sensitive cells after prior therapy.[8,9] Standard chemoimmunotherapy is particularly ineffective for patients with TP53 pathogenic variants. Targeted therapies for the B-cell receptor (Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors), surface antigens (like chimeric antigen receptor T-cell and bispecific antibodies), and BCL-2 inhibitors are more applicable.

Prognosis

MCL is not considered curable in the standard sense because eventual relapse is a certainty. However, many older patients achieve a functional cure, surviving until death from other causes while in MCL remission. There is no evidence that the distinction between the nodal and non-nodal subtypes maintains its relevance in patients with multiply relapsed or refractory disease.

References

- Armitage JO, Longo DL: Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 386 (26): 2495-2506, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Campo E, Jaffe ES, Cook JR, et al.: The International Consensus Classification of Mature Lymphoid Neoplasms: a report from the Clinical Advisory Committee. Blood 140 (11): 1229-1253, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, et al.: The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia 36 (7): 1720-1748, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Clot G, Jares P, Giné E, et al.: A gene signature that distinguishes conventional and leukemic nonnodal mantle cell lymphoma helps predict outcome. Blood 132 (4): 413-422, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fenske TS: Frontline Therapy in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: When Clinical Trial and Real-World Data Collide. J Clin Oncol 41 (3): 452-459, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cohen JB, Han X, Jemal A, et al.: Deferred therapy is associated with improved overall survival in patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer 122 (15): 2356-63, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Greenwell IB, Staton AD, Lee MJ, et al.: Complex karyotype in patients with mantle cell lymphoma predicts inferior survival and poor response to intensive induction therapy. Cancer 124 (11): 2306-2315, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dreyling M, Klapper W, Rule S: Blastoid and pleomorphic mantle cell lymphoma: still a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge! Blood 132 (26): 2722-2729, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jain P, Dreyling M, Seymour JF, et al.: High-Risk Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Definition, Current Challenges, and Management. J Clin Oncol 38 (36): 4302-4316, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lew TE, Minson A, Dickinson M, et al.: Treatment approaches for patients with TP53-mutated mantle cell lymphoma. Lancet Haematol 10 (2): e142-e154, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jain P, Wang M: High-risk MCL: recognition and treatment. Blood 145 (7): 683-695, 2025. [PUBMED Abstract]

Stage Information for Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Stage is important in selecting a treatment for patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). Positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) is usually part of the staging evaluation for all patients with lymphoma.

Patients with MCL commonly have involvement of the following sites:

- Contiguous or noncontiguous lymph nodes.

- Gastrointestinal tract, especially colonic polyposis.

- Extranodal presentations.

- Bone marrow.

- Spleen.

Rarely, cytological examination of cerebrospinal fluid may be positive in patients with MCL. Lumbar puncture is not a typical staging procedure, but it is considered for patients with mantle cell blastoid variant or 17p deletion/TP53-altered disease.

Most patients with MCL present with advanced (stage III or stage IV) disease, often identified by PET-CT scans or biopsies of the bone marrow when indicated by PET positivity. In a retrospective review of over 32,000 cases of lymphoma in France, up to 40% of diagnoses were made by core needle biopsy, and 60% were made by excisional biopsy.[1] After expert review, core needle biopsy provided a definite diagnosis in 92.3% of cases; excisional biopsy provided a definite diagnosis in 98.1% of cases (P < .0001). Laparoscopic biopsy or laparotomy is not required for staging but rarely may be necessary to establish a diagnosis or histological type.[2]

PET-CT scans with fluorine F 18-fludeoxyglucose are used for initial staging and may also be used for follow-up after therapy.[3] Multiple studies have demonstrated that routine interim PET scans after two to four cycles of therapy do not provide reliable prognostic information in aggressive lymphomas, and they are not recommended for MCL.[4-7]

For patients with MCL, a positive PET result after therapy confers a worse prognosis. However, it is unclear whether a positive PET result is predictive when alternative therapy is implemented.[8]

Staging Subclassification System

Lugano classification

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has adopted the Lugano classification to evaluate and stage lymphoma.[9] The Lugano classification system replaces the Ann Arbor classification system, which was adopted in 1971 at the Ann Arbor Conference,[10] with some modifications 18 years later from the Cotswolds meeting.[11,12]

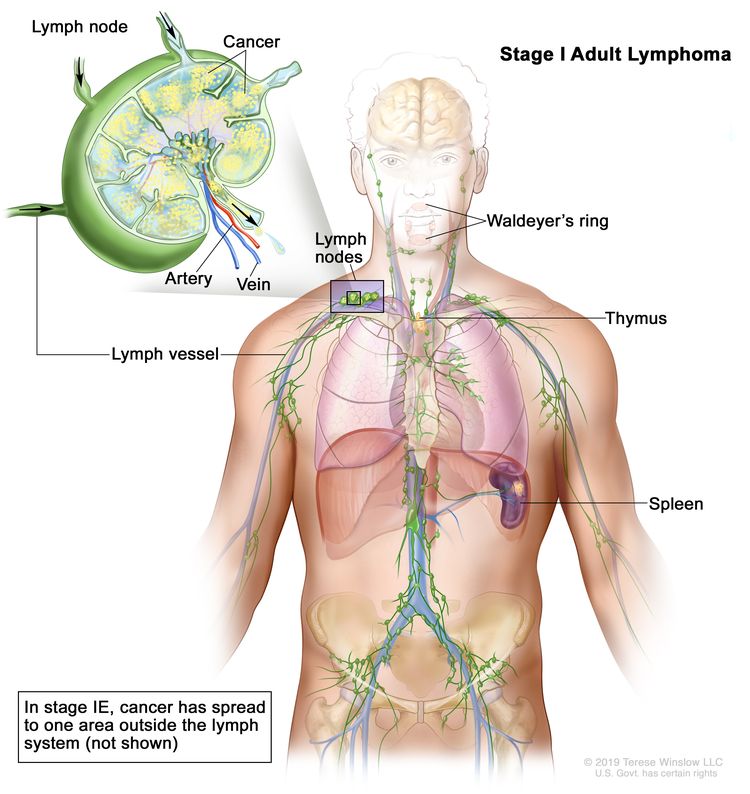

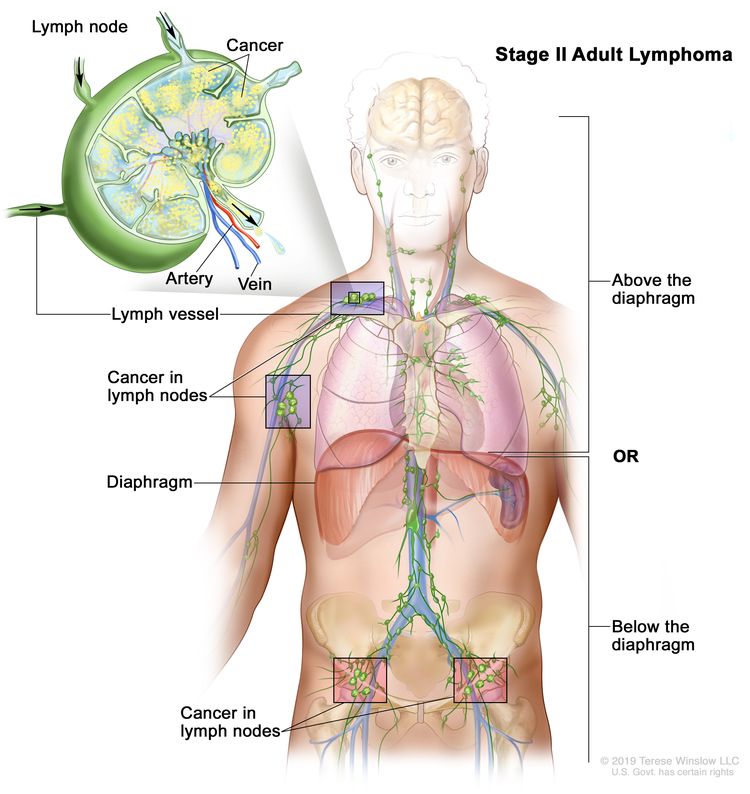

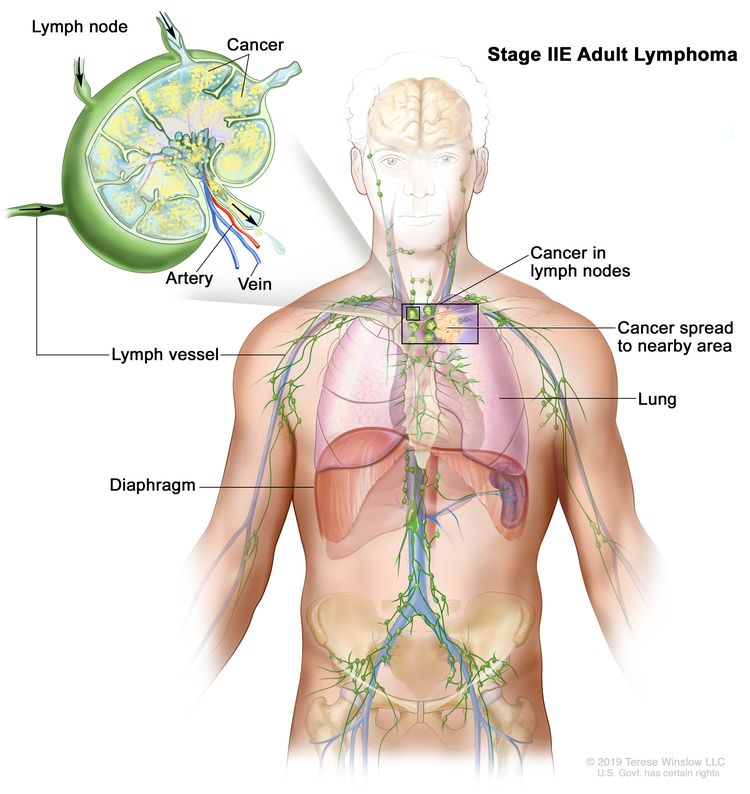

| Stage | Stage Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| CSF = cerebrospinal fluid; MCL = mantle cell lymphoma; NHL = non-Hodgkin lymphoma. | ||

| aHodgkin and Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 937–58. | ||

| bStage II bulky may be considered either early or advanced stage based on lymphoma histology and prognostic factors. | ||

| cThe definition of disease bulk varies according to lymphoma histology. Precise measurements have not been determined for MCL, and proposals range from ≥5 cm to ≥10 cm. | ||

| Limited stage | ||

| I | Involvement of a single lymphatic site (i.e., nodal region, Waldeyer’s ring, thymus, or spleen). |

|

| IE | Single extralymphatic site in the absence of nodal involvement. | |

| II | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm. |

|

| IIE | Contiguous extralymphatic extension from a nodal site with or without involvement of other lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm. |

|

| II bulkyb | Stage II with disease bulk.c | |

| Advanced stage | ||

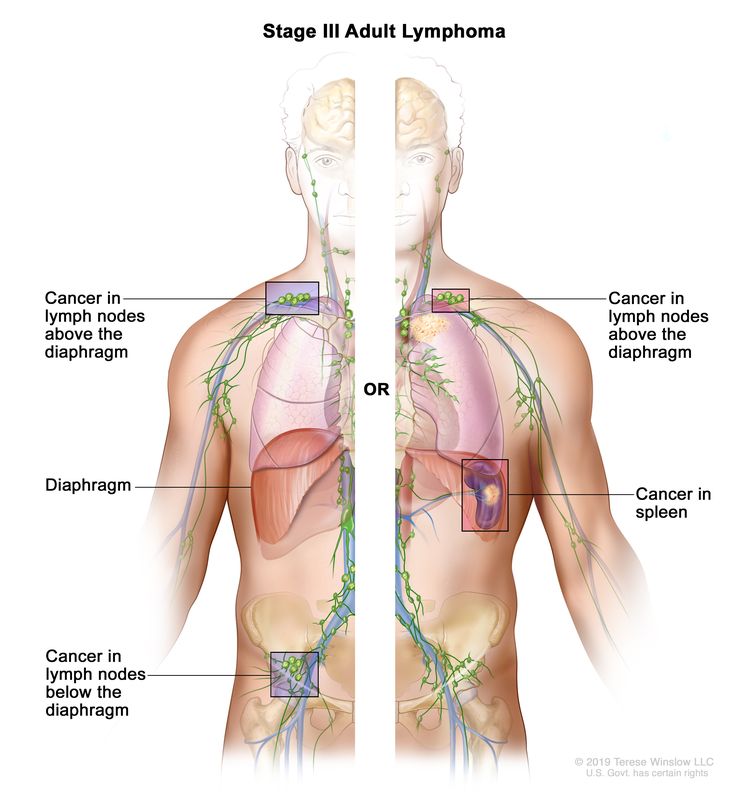

| III | Involvement of lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm; nodes above the diaphragm with spleen involvement. |

|

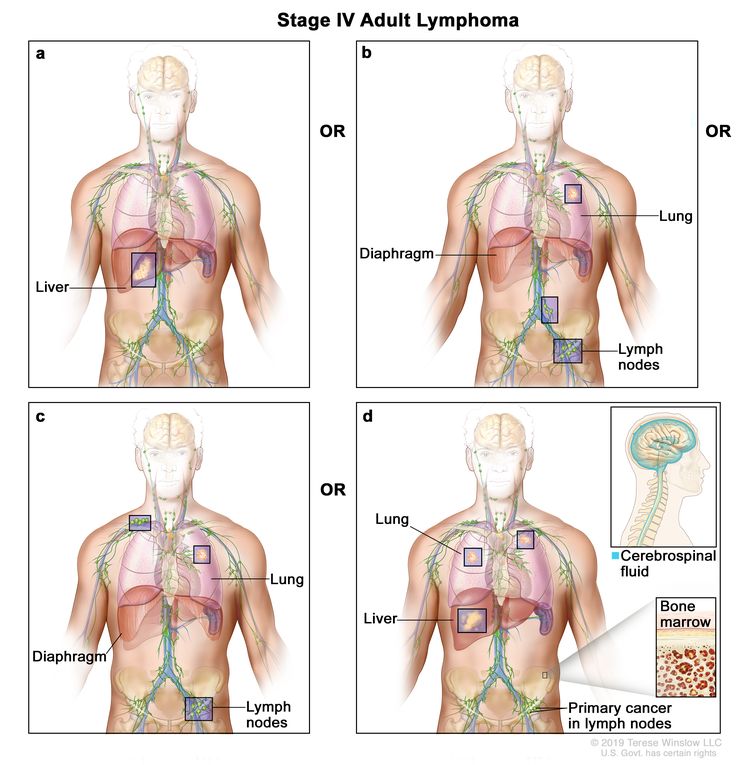

| IV | Diffuse or disseminated involvement of one or more extralymphatic organs, with or without associated lymph node involvement; or noncontiguous extralymphatic organ involvement in conjunction with nodal stage II disease; or any extralymphatic organ involvement in nodal stage III disease. Stage IV includes any involvement of the CSF, bone marrow, liver, or multiple lung lesions (other than by direct extension in stage IIE disease). |

|

| Note: Hodgkin lymphoma uses A or B designation with stage group. A/B is no longer used in NHL. | ||

Occasionally, specialized staging systems are used. The physician should be aware of the system used in a specific report.

The E designation is used when extranodal lymphoid malignancies arise in tissues separate from, but near, the major lymphatic aggregates. Stage IV refers to disease that is diffusely spread throughout an extranodal site, such as the liver. If pathological proof of involvement of one or more extralymphatic sites has been documented, the symbol for the site of involvement, followed by a plus sign (+), is listed.

| N = nodes | H = liver | L = lung | M = bone marrow |

| S = spleen | P = pleura | O = bone | D = skin |

Current practice assigns a clinical stage based on the findings of the clinical evaluation and a pathological stage based on the findings from invasive procedures beyond the initial biopsy.

Several other factors that are not included in the above staging system are important for the staging and prognosis of patients with MCL. These factors include:

- Age.

- Performance status.

- Tumor size.

- Lactate dehydrogenase level.

- The number of extranodal sites.

- TP53 status (pathogenic variant or deletion).

- Ki-67 cell proliferation rate.

- Complex karyotype or gene expression.

- CCND1 or ATM pathogenic variants or deletions.

- Hypermutated or unmutated IGHV.

- Beta-2 microglobulin.

MCL has demonstrated heterogeneous and variable clinical courses. Many prognostic factors have been identified, and mantle cell international prognostic scores have been devised. While these indicators help designate the need for therapy, they have not proven useful for selection of treatment. The one exception is the poor performance of standard chemotherapeutic agents with immunotherapy in patients with the highest-risk disease, as described previously.

References

- Syrykh C, Chaouat C, Poullot E, et al.: Lymph node excisions provide more precise lymphoma diagnoses than core biopsies: a French Lymphopath network survey. Blood 140 (24): 2573-2583, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mann GB, Conlon KC, LaQuaglia M, et al.: Emerging role of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 16 (5): 1909-15, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Barrington SF, Mikhaeel NG, Kostakoglu L, et al.: Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J Clin Oncol 32 (27): 3048-58, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Horning SJ, Juweid ME, Schöder H, et al.: Interim positron emission tomography scans in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: an independent expert nuclear medicine evaluation of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group E3404 study. Blood 115 (4): 775-7; quiz 918, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Moskowitz CH, Schöder H, Teruya-Feldstein J, et al.: Risk-adapted dose-dense immunochemotherapy determined by interim FDG-PET in Advanced-stage diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 28 (11): 1896-903, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pregno P, Chiappella A, Bellò M, et al.: Interim 18-FDG-PET/CT failed to predict the outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients treated at the diagnosis with rituximab-CHOP. Blood 119 (9): 2066-73, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sun N, Zhao J, Qiao W, et al.: Predictive value of interim PET/CT in DLBCL treated with R-CHOP: meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2015: 648572, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pyo J, Won Kim K, Jacene HA, et al.: End-therapy positron emission tomography for treatment response assessment in follicular lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cancer Res 19 (23): 6566-77, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp. 937–58.

- Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, et al.: Report of the Committee on Hodgkin's Disease Staging Classification. Cancer Res 31 (11): 1860-1, 1971. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, et al.: Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin's disease: Cotswolds meeting. J Clin Oncol 7 (11): 1630-6, 1989. [PUBMED Abstract]

- National Cancer Institute sponsored study of classifications of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: summary and description of a working formulation for clinical usage. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Pathologic Classification Project. Cancer 49 (10): 2112-35, 1982. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment Option Overview for Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Once the diagnosis of mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is established and staging is completed (usually with positron emission tomography–computed tomography, although colonoscopy, bone marrow biopsy, or lumbar puncture may be indicated in selected cases), laboratory testing is performed. This testing allows a distinction to be made among the indolent non-nodal leukemic subtype (20% of patients with MCL), the more aggressive nodal subtype, or the hyperaggressive blastoid or TP53-altered subtype which confers the worst prognosis. Clinical judgment may be required for patients with both indolent and aggressive features. For more information about laboratory testing, see the sections on Clinical Features and Stage Information for Mantle Cell Lymphoma.

| MCL Subtype | Treatment Options | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BR = bendamustine and rituximab; BTK = Bruton tyrosine kinase; CAR = chimeric antigen receptor; R2 regimen = rituximab and lenalidomide; R-CHOP = rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; R-DHAP = rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin; R-HCVAD = rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone; R-MA = rituximab, methotrexate, and cytarabine. | |||

| Non-nodal leukemic subtype: Early-stage (IA, IIA) stable or slowly progressing disease | Watchful waiting | ||

| Radiation therapy | |||

| Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (rituximab, obinutuzumab) | |||

| BTK inhibitors (acalabrutinib) | |||

| R2 regimen | |||

| BR | |||

| Nodal aggressive subtype: Advanced-stage lymph nodes (stage IIB, III, IV) | BTK inhibitors with or without anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies | ||

| Chemoimmunotherapy (BR; R-CHOP/R-DHAP; R-HCVAD/R-MA) | |||

| R2 regimen | |||

| Rituximab alone (in older patients with comorbidities who cannot take BTK inhibitors) | |||

| Hyperaggressive blastoid or TP53-altered subtype | BTK inhibitor + rituximab (or obinutuzumab) + BCL-2 inhibitor (venetoclax) | ||

| Consolidation with T-cell directed therapy such as allogeneic stem cell transplant, CAR T-cell therapy, or bispecific antibody therapy | |||

| Clinical trials | |||

Before beginning systemic therapy, patients should be screened for active hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or HIV.[1] Patients with detectable hepatitis B virus (HBV) benefit from prophylaxis with entecavir if their treatment plan includes rituximab, Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors, or chemoimmunotherapy. Patients with a resolved HBV infection (defined as hepatitis B surface antigen-negative but hepatitis B core antibody-positive) are at risk of reactivation of HBV and require active monitoring of HBV DNA. For patients who received rituximab or obinutuzumab therapy, the risk of reactivation was 10% to 15%; prophylaxis reduced this risk to 2% in a retrospective study.[2] Similarly, prophylaxis for herpes zoster with valacyclovir or acyclovir and prophylaxis for pneumocystis with trimethoprim/sulfa or dapsone are usually given to all patients receiving systemic therapy.

Summary of Therapy for MCL

The following agents, alone or in combination, represent targeted biological therapy options that may enable chemotherapy-free treatment strategies for most patients with MCL:[3]

- BTK inhibitors: acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib, ibrutinib, and pirtobrutinib.

- Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies: rituximab and obinutuzumab.

- BCL-2 inhibitor: venetoclax.

- Immune stimulator: lenalidomide.

Chemoimmunotherapy with BR (bendamustine and rituximab) or with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone)/R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin) is still considered a standard option for younger fit patients. Most patients can avoid autologous stem cell transplant (SCT), but maintenance therapy with rituximab for at least 2 to 3 years remains the standard of care after first-line induction therapy. The highest-risk patients may best respond to combinations of biological targeted therapies, followed by consolidation with allogeneic SCT or chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy.[4,5]

Routine administration of central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis in patients with high-risk MCL has never been studied in a prospective randomized trial. The use of intrathecal or intravenous high-dose methotrexate or the use of systemic therapies with CNS penetration such as BTK inhibitors, high-dose cytarabine, or venetoclax have not been studied or proven efficacious in this situation.[6]

Outside the context of clinical trials, the use of measurable residual disease (MRD) testing has not been shown to be predictive for directing therapy for patients with MCL. In a retrospective analysis of a prospective randomized clinical trial, while MRD negativity after rituximab maintenance therapy was prognostic for a better outcome, continuation of maintenance rituximab prolonged progression-free survival and overall survival the most among patients with MRD-negative disease.[7][Level of evidence C1] Stopping maintenance rituximab was not indicated in patients with MRD-negative disease, negating any possible change in therapy based on that status.

References

- Dong HJ, Ni LN, Sheng GF, et al.: Risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients receiving rituximab-chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Clin Virol 57 (3): 209-14, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kusumoto S, Arcaini L, Hong X, et al.: Risk of HBV reactivation in patients with B-cell lymphomas receiving obinutuzumab or rituximab immunochemotherapy. Blood 133 (2): 137-146, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Martin P, Ruan J, Leonard JP: The potential for chemotherapy-free strategies in mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 130 (17): 1881-1888, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fenske TS, Zhang MJ, Carreras J, et al.: Autologous or reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chemotherapy-sensitive mantle-cell lymphoma: analysis of transplantation timing and modality. J Clin Oncol 32 (4): 273-81, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jain P, Wang M: High-risk MCL: recognition and treatment. Blood 145 (7): 683-695, 2025. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jain P, Dreyling M, Seymour JF, et al.: High-Risk Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Definition, Current Challenges, and Management. J Clin Oncol 38 (36): 4302-4316, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hoster E, Delfau-Larue MH, Macintyre E, et al.: Predictive Value of Minimal Residual Disease for Efficacy of Rituximab Maintenance in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Results From the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Elderly Trial. J Clin Oncol 42 (5): 538-549, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Indolent Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Asymptomatic patients with indolent mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), a low burden of lymphadenopathy, and no significant splenomegaly or cytopenias may benefit from a watchful waiting approach. This approach has been demonstrated in several retrospective series.[1,2][Level of evidence C3] Because most patients with MCL are older than 60 years and MCL is not treated with curative intent, the quality-of life impact of treatment-related toxicities (both physical and financial) must be considered.

When patients with indolent MCL require therapy, a lower-intensity approach is preferred, but there is no standard approach due to the lack of clinical trials for this subgroup.

Induction chemotherapy regimens may be used for symptomatic progressive disease. These regimens range in intensity from rituximab alone to rituximab plus acalabrutinib (or ibrutinib or zanubrutinib), rituximab plus lenalidomide (R2), or bendamustine and rituximab (BR).

A prospective randomized trial included 373 patients with previously untreated MCL. A total of 87% of patients were aged 60 years or older. The study compared (1) BR versus BR plus bortezomib (BVR) as induction regimens and (2) rituximab versus R2 as maintenance regimens.[3]

- With a median follow-up of 7.5 years, there was no difference in the median progression-free survival (PFS) for patients who received BR compared with patients who received BVR (5.5 vs. 6.4 years; hazard ratio [HR], 0.90; 90% confidence interval [CI], 0.70–1.16).[3][Level of evidence B1]

- Independent of the induction therapy, there was no difference in the median PFS for patients who received rituximab versus patients who received R2 (5.9 vs. 7.2 years; HR, 0.84; 90% CI, 0.62–1.15).[3][Level of evidence B1]

Summary: BR induction therapy followed by maintenance therapy with rituximab remains a standard-of-care option. No benefit was noted in trials that incorporated early bortezomib or lenalidomide in the standard option. However, for many patients with indolent MCL, BR can be avoided by starting with rituximab alone and adding a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor (such as acalabrutinib, ibrutinib, or zanubrutinib) if the response is not adequate after 4 to 8 weeks of therapy.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Martin P, Chadburn A, Christos P, et al.: Outcome of deferred initial therapy in mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 27 (8): 1209-13, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cohen JB, Han X, Jemal A, et al.: Deferred therapy is associated with improved overall survival in patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer 122 (15): 2356-63, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Smith MR, Jegede OA, Martin P, et al.: Randomized study of induction with bendamustine-rituximab ± bortezomib and maintenance with rituximab ± lenalidomide for MCL. Blood 144 (10): 1083-1092, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Aggressive Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Clinical trials have not determined which therapeutic option offers the best long-term survival for patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). The situation is unclear because MCL is a relatively rare disease (4,000 new cases per year in the United States), and study evidence has accrued slowly over the past decade. A historical perspective may help to explain the state of the evidence.

MCL was first described in the 1980s as a distinct entity from small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic lymphoma or follicular lymphoma. When treated with oral alkylators and infusional cytotoxic agents available at the time, MCL appeared to relapse sooner and more frequently than other indolent lymphomas. When purine analogues also proved ineffective in the 1990s, MCL was viewed as an aggressive lymphoma without a discernible cure. This view ultimately led to an aggressive treatment paradigm that incorporated all available modalities in the early 2000s: R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) followed by high-dose cytarabine with or without a platinum agent, plus autologous stem cell transplant (SCT) plus rituximab maintenance.[1,2]

Chemoimmunotherapy

Evidence (chemoimmunotherapy):

- In a prospective trial, 560 patients older than 60 years and not eligible for SCT were randomly assigned to receive induction therapy with either R-CHOP or R-FC (rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide) for six to eight cycles. Patients with disease response (n = 316) were then randomly assigned to receive maintenance therapy with either rituximab or interferon alfa.[3]

- Focusing on the randomized induction therapy (n = 560), with a median follow-up of 7.6 years, the median overall survival (OS) was 6.4 years in the R-CHOP group and 3.9 years in the R-FC group (P = .0054).[3][Level of evidence A1]

- Focusing on the randomized maintenance therapy (n = 316 responders), with a median follow-up of 8 years, the median OS was 9.8 years in the rituximab group and 7.1 years in the interferon alfa group (P = .009).[3][Level of evidence A1]

- A randomized trial compared bendamustine and rituximab (BR) with R-CHOP. Progression free-survival (PFS) improved in patients who received BR (35 months) compared with patients who received R-CHOP (22 months) (hazard ratio [HR], 0.49; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.28–0.79; P = .004). There was no difference in OS.[4][Level of evidence B1]

- This trial failed to show any benefit for rituximab maintenance therapy after BR.

- A prospective randomized trial of 487 patients compared VR-CAP (bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone) with R-CHOP.[5]

- With a median follow-up of 82 months, the median OS was longer in the VR-CAP group (90.7 months) than in the R-CHOP group (55.7 months) (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.51−0.85; P = .001).[5][Level of evidence A1]

- A prospective randomized trial from the European MCL Network included 497 patients younger than 65 years. The trial compared six cycles of R-CHOP with six cycles of alternating R-CHOP and R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin), with both groups then receiving autologous SCT.[1,2][Level of evidence B1]

- With a median follow-up of 10.6 years, the 10-year PFS rate was 73% for patients who received R-DHAP and 57% for patients who received R-CHOP (HR, 0.56; P = .038). There was no difference in the 10-year OS rates (60% [R-DHAP] vs. 55% [R-CHOP]; HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.61–1.06; P = .12).[6][Level of evidence B1]

This trial is often referenced by subsequent articles to assert a role for cytarabine in induction therapy, but the ultimate lack of survival advantage casts doubt on this assertion. This regimen is clearly not applicable for older, less fit patients with comorbidities who are not eligible for transplant.

Summary: By the 2010s, the standard of care for older patients with comorbidities was the BR regimen. For younger fit patients with MCL, the standard of care was R-CHOP/R-DHAP, followed by autologous SCT consolidation and rituximab maintenance therapy, based on the results of the trial by the European MCL Network.[1,2]

Since 2015, clinical trials have focused on the necessity of autologous SCT consolidation and the use of high-dose cytarabine during induction therapy. As a result of randomized trials that incorporated the Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors ibrutinib or acalabrutinib, sufficient evidence exists to avoid autologous SCT and high-dose cytarabine in most patients.

Treatment Options to Avoid Autologous SCT Consolidation

Evidence (treatment options to avoid autologous SCT consolidation):

- The prospective, randomized TRIANGLE trial (NCT02858258) trial included 870 patients aged 65 years or younger with previously untreated MCL who were fit enough for autologous SCT. There were three study arms. The primary end point was failure-free survival (FFS), and the secondary end point was OS.[7,8] The three arms included:

- Arm A: Standard therapy at the start of the trial with R-CHOP/R-DHAP followed by autologous SCT consolidation and rituximab maintenance therapy.

- Arm A+I: Ibrutinib plus R-CHOP/R-DHAP followed by autologous SCT consolidation and ibrutinib plus rituximab maintenance therapy.

- Arm I: Ibrutinib plus R-CHOP/R-DHAP with no consolidation and ibrutinib plus rituximab maintenance therapy.

- With a median follow-up of 53 months, results were published in abstract form. The 3-year OS rate was 90% for arm A+I versus 85% for arm A (HR, 0.61; P = .0069), and the 3-year OS rate was 91% for arm I versus 85% for arm A (HR, 0.59; P = .0041).[8][Level of evidence A1]

- Also published in abstract form, after a median follow-up of 53 months, the role of autologous SCT was evaluated by comparing the FFS of arm A+I (with autologous SCT) with the FFS of arm I (without autologous SCT) (86% vs. 85%, respectively; HR, 0.86; P = .56), which was not significantly different.[8][Level of evidence B1]

- Toxicity was highest in the autologous SCT arms, as expected.

Summary: When patients received ibrutinib and a high-dose chemoimmunotherapy regimen (including cytarabine), the addition of ibrutinib led to superior outcomes by 5% for OS. Autologous SCT did not add efficacy to the ibrutinib-containing regimens but did add toxicity.

- The ECOG 4151 trial (NCT03267433), published in abstract form, included 650 patients younger than 71 years with previously untreated MCL who were eligible for autologous SCT. The trial allowed any standard induction therapy regimen. Most patients received R-CHOP or R-DHAP induction therapy, and 27% received BR. All patients received rituximab maintenance therapy. Patients found to have measurable residual disease (MRD)–negative MCL in the blood and marrow (80%, n = 516) were randomly assigned to receive either autologous SCT plus 3 years of maintenance therapy with rituximab or 3 years of maintenance therapy with rituximab alone.[9]

- With a median follow-up of 42 months, there was no difference in 3-year OS rates, at 82.1% for patients who received autologous SCT and 82.7% for patients who did not receive autologous SCT (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.71–1.74; P = .66). This OS HR crossed the futility boundary.[9][Level of evidence A1]

Summary: With the introduction of ibrutinib and other BTK inhibitors that can be used during induction therapy, maintenance therapy, or at relapse, most patients can avoid autologous SCT.

- A retrospective analysis included 1,265 patients aged 65 years or younger with MCL who were transplant-eligible. The analysis showed no benefit for autologous SCT in time-to-next treatment (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.68–1.03) or OS (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.63–1.18).[10][Level of evidence C3]

Treatment Options to Avoid High-Dose Cytarabine

Evidence (treatment options to avoid high-dose cytarabine):

- A three-arm prospective randomized trial, published in abstract form, included 359 patients with previously untreated MCL. The trial evaluated complete remission rates after induction therapy (defined as a complete metabolic response by positron emission tomography–computed tomography, undetectable MRD by blood and bone marrow, and PFS).[11] The three treatment arms included:

- BR for three cycles plus CR (high-dose cytarabine plus rituximab).

- BR plus CR plus A (acalabrutinib).

- BR plus A (omitting cytarabine).

- With a median follow-up of 27.9 months, the 1-year PFS rate was 86% for BR plus CR, 89% for BR plus CR plus A, and 87% for BR plus A. The 1-year OS rate was 94% for BR plus CR, 98% for BR plus CR plus A, and 95% for BR plus A.

- The trial was closed because of an interim futility analysis for superiority of any treatment arm. However, BR plus A was the least toxic arm.

Summary: Although adding acalabrutinib to BR plus CR did not improve efficacy, adding acalabrutinib to BR (and avoiding cytarabine) was equally effective. Since the pivotal initial trial by the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network [1,2] failed to confirm OS benefit at 10 years (without post-hoc adjustments), this finding suggests that cytarabine is not a mandatory agent in some induction therapy regimens.

It remains unclear whether induction therapy that combines chemotherapy with BTK inhibitors can be replaced by BTK inhibitors alone or BTK inhibitors in combination with CD20-directed monoclonal antibodies like rituximab or obinutuzumab.

BTK inhibitors With or Without Other Drugs

Evidence (BTK inhibitors with or without other drugs):

- A prospective trial, published in abstract form, included 397 patients aged 60 years and older with previously untreated MCL. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either ibrutinib plus rituximab or BR.[12]

- With a median follow-up of 47.9 months, the PFS rate was 65.3% for patients who received ibrutinib plus rituximab and 42.4% for patients who received BR (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.52–0.90; P = .003).[12][Level of evidence B1]

- A prospective randomized trial (SHINE [NCT01776840]) included 523 patients aged 65 years and older with previously untreated MCL. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either ibrutinib plus BR or placebo plus BR. The primary end point was PFS.[13]

- With a median follow-up of 84.7 months, the median PFS was 80.6 months for patients who received ibrutinib plus BR and 52.9 months for patients who received placebo plus BR (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.59–0.96; P = .01). There was no difference in the 7-year OS rate (55.0% vs. 56.8%; HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.81–1.40).[13][Level of evidence B1]

- The magnitude of benefit for PFS results contrasted with the lower 7-year OS may cast doubt on the long-term safety of the ibrutinib plus BR combination. Infectious deaths in the combination group contributed to the lack of survival advantage.

- Further trials are required to determine if ibrutinib alone can achieve the same results without adding BR, potentially avoiding the increased toxicities and infectious deaths from including bendamustine.

- In a prospective randomized trial, 280 patients with relapsed or refractory MCL received either ibrutinib or temsirolimus.[14]

- With a median follow-up of 15 months, the median PFS was 14.6 months in the ibrutinib group and 6.2 months in the temsirolimus group (HR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.32–0.58; P < .0001).[14][Level of evidence B1]

- In a phase II trial of previously untreated patients older than 64 years with MCL, 50 patients received ibrutinib plus rituximab.[15]

- With a median follow-up of 45 months, the overall response rate was 96%, the complete response rate was 71%, the 3-year PFS rate was 87%, and the 3-year OS rate was 94%.[15][Level of evidence C3]

- In a phase II trial of 131 previously untreated patients with MCL aged 65 years or younger, 1 year of ibrutinib plus 4 weeks of rituximab resulted in a complete response rate of 89% prior to any chemotherapy consolidation.[16][Level of evidence C3]

- A phase II trial using ibrutinib plus rituximab included asymptomatic patients with previously untreated MCL.[17]

- The complete response rate was 87%.[17][Level of evidence C3]

- Ibrutinib was combined with another active agent, venetoclax, in a phase II study of 23 patients with relapsed or refractory MCL.[18]

- With a median follow-up of 7 years 4 months, the 7-year PFS rate was 30% (95% CI, 14%–49%), and the 7-year OS rate was 43% (95% CI, 23%–26%).[18][Level of evidence C3]

- A randomized prospective trial (SYMPATICO [NCT03112174]) included 267 patients with relapsed or refractory MCL. The trial compared (1) ibrutinib plus venetoclax for 2 years followed by ibrutinib until disease progression versus (2) ibrutinib plus placebo followed by ibrutinib.[19]

- With a median follow-up of 51.2 months (interquartile range, 48.2–55.3), the median PFS was 31.9 months (95% CI, 22.8–47.0) in the ibrutinib-venetoclax group and 22.1 months (16.5–29.5) in the ibrutinib-placebo group (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.47–0.88; P = .0052).[19]

- Acalabrutinib was evaluated in a phase II study of 124 patients with relapsed or refractory MCL.[20]

- There was an 81% overall response rate, 40% complete response rate, and 67% 1-year PFS rate.[20][Level of evidence C3]

- Zanubrutinib was evaluated in a phase II study of 86 patients with relapsed or refractory MCL.[21]

- After a median follow-up of 35.3 months, the overall response rate was 84%, the complete response rate was 78%, and the median PFS was 33.0 months.[21][Level of evidence C3]

Summary: Ibrutinib and other BTK inhibitors such as acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib, and the noncovalent inhibitor pirtobrutinib are used in multiple clinical trials either alone or mostly in combination with rituximab, obinutuzumab, or venetoclax. Multiple agents are combined in clinical trials for the highest-risk patients with TP53 alterations, blastoid morphology, or high Ki-67. Further clinical trials may establish BTK inhibitors without chemotherapy as a standard first-line regimen for patients with standard-risk MCL.

Highest-Risk Patients With Blastoid Morphology and/or a TP53 Pathogenic Variant

Although the prior standard of care for untreated MCL was chemoimmunotherapy including high-dose cytarabine and autologous SCT, patients with TP53-altered MCL have had poor outcomes with this regimen, with a median PFS of under 1 year.[22,23] BTK inhibitors combined with other immunological or targeted molecules are particularly applicable for testing. Consolidation with allogeneic SCT or trials studying chimeric antigen receptor T cells or bispecific antibodies are also warranted after treatment response.[24]

Evidence (new combinations for highest-risk patients):

- A phase II trial included 25 patients with TP53 pathogenic variants who required therapy because of significant constitutional symptoms, cytopenias, symptomatic splenomegaly, progressive nodal involvement, or significant organ compression or involvement. Patients received zanubrutinib (the selective BTK inhibitor), obinutuzumab (the humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody), and venetoclax (the BCL inhibitor, with a 5-week ramp-up beginning on day 1 of the third cycle).[25]

- With a median follow-up of 28.2 months, the overall response rate was 96% and the complete response rate was 68% at the start of cycle three. The 2-year PFS rate was 72% (95% CI, 56%–92%), and the 2-year OS rate was 76% (95% CI, 79%–100%).[25][Level of evidence C3]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Hermine O, Hoster E, Walewski J, et al.: Addition of high-dose cytarabine to immunochemotherapy before autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients aged 65 years or younger with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL Younger): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. Lancet 388 (10044): 565-75, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hermine O, Jiang L, Walewski J, et al.: Addition of high-dose cytarabine to immunochemotherapy before autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients aged 65 years or younger with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL younger): a long-term follow-up of the randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. [Abstract] Blood 138 (Suppl 1); A-380, 2021.

- Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hoster E, Hermine O, et al.: Treatment of Older Patients With Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL): Long-Term Follow-Up of the Randomized European MCL Elderly Trial. J Clin Oncol 38 (3): 248-256, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al.: Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 381 (9873): 1203-10, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Robak T, Jin J, Pylypenko H, et al.: Frontline bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (VR-CAP) versus rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) in transplantation-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma: final overall survival results of a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 19 (11): 1449-1458, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hermine O, Jiang L, Walewski J, et al.: High-Dose Cytarabine and Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Long-Term Follow-Up of the Randomized Mantle Cell Lymphoma Younger Trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol 41 (3): 479-484, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dreyling M, Doorduijn J, Giné E, et al.: Ibrutinib combined with immunochemotherapy with or without autologous stem-cell transplantation versus immunochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in previously untreated patients with mantle cell lymphoma (TRIANGLE): a three-arm, randomised, open-label, phase 3 superiority trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. Lancet 403 (10441): 2293-2306, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dreyling M, Doorduijn JK, Gine E, et al.: Role of autologous stem cell transplantation in the context of ibrutinib-containing first-line treatment in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma: results from the randomized Triangle trial by the European MCL Network. [Abstract] Blood 144 (Suppl 1) A-240, 240-2, 2024.

- Fenske TS, Wang XV, Till BG, et al.: Lack of benefit of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (auto-HCT) in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) patients (pts) in first complete remission (CR) with undetectable minimal residual disease (uMRD): initial report from the ECOG-ACRIN EA4151 phase 3 randomized trial. [Abstract] Blood 144 (Suppl 2): A-LBA-6, 2024.

- Martin P, Cohen JB, Wang M, et al.: Treatment Outcomes and Roles of Transplantation and Maintenance Rituximab in Patients With Previously Untreated Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Results From Large Real-World Cohorts. J Clin Oncol 41 (3): 541-554, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wagner-Johnston N, Jegede O, Spurgeon SE, et al.: Addition or substitution of acalabrutinib in intensive frontline chemoimmunotherapy for patients ≤ 70 years old with mantle cell lymphoma: outcomes of the 3-arm randomized phase II intergroup trial ECOG-ACRIN EA4181. [Abstract] Blood 144 (Suppl 1): A-236, 2024.

- Lewis DJ, Jerkeman M, Sorrell L, et al.: Ibrutinib-rituximab is superior to rituximab-chemotherapy in previously untreated older mantle cell lymphoma patients: results from the international randomised controlled trial, Enrich. [Abstract] Blood 144 (Suppl 1): A-235, 2024.

- Wang ML, Jurczak W, Jerkeman M, et al.: Ibrutinib plus Bendamustine and Rituximab in Untreated Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 386 (26): 2482-2494, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dreyling M, Jurczak W, Jerkeman M, et al.: Ibrutinib versus temsirolimus in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma: an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 387 (10020): 770-8, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jain P, Zhao S, Lee HJ, et al.: Ibrutinib With Rituximab in First-Line Treatment of Older Patients With Mantle Cell Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 40 (2): 202-212, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang ML, Jain P, Zhao S, et al.: Ibrutinib-rituximab followed by R-HCVAD as frontline treatment for young patients (≤65 years) with mantle cell lymphoma (WINDOW-1): a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 23 (3): 406-415, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Giné E, de la Cruz F, Jiménez Ubieto A, et al.: Ibrutinib in Combination With Rituximab for Indolent Clinical Forms of Mantle Cell Lymphoma (IMCL-2015): A Multicenter, Open-Label, Single-Arm, Phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol 40 (11): 1196-1205, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Handunnetti SM, Anderson MA, Burbury K, et al.: Seven-year outcomes of venetoclax-ibrutinib therapy in mantle cell lymphoma: durable responses and treatment-free remissions. Blood 144 (8): 867-872, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang M, Jurczak W, Trneny M, et al.: Ibrutinib plus venetoclax in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (SYMPATICO): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 26 (2): 200-213, 2025. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang M, Rule S, Zinzani PL, et al.: Acalabrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (ACE-LY-004): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 391 (10121): 659-667, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Song Y, Zhou K, Zou D, et al.: Zanubrutinib in relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma: long-term efficacy and safety results from a phase 2 study. Blood 139 (21): 3148-3158, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Eskelund CW, Dahl C, Hansen JW, et al.: TP53 mutations identify younger mantle cell lymphoma patients who do not benefit from intensive chemoimmunotherapy. Blood 130 (17): 1903-1910, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ferrero S, Rossi D, Rinaldi A, et al.: KMT2D mutations and TP53 disruptions are poor prognostic biomarkers in mantle cell lymphoma receiving high-dose therapy: a FIL study. Haematologica 105 (6): 1604-1612, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fenske TS, Zhang MJ, Carreras J, et al.: Autologous or reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chemotherapy-sensitive mantle-cell lymphoma: analysis of transplantation timing and modality. J Clin Oncol 32 (4): 273-81, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kumar A, Soumerai J, Abramson JS, et al.: Zanubrutinib, obinutuzumab, and venetoclax for first-line treatment of mantle cell lymphoma with a TP53 mutation. Blood 145 (5): 497-507, 2025. [PUBMED Abstract]

Maintenance Therapy After Induction Therapy for Mantle Cell Lymphoma

The use of maintenance therapy with rituximab alone or combined with a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor after induction therapy or any consolidation has been the standard of care for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL). The duration of maintenance therapy has ranged from 3 years until time of disease relapse.

Rituximab Maintenance Therapy Alone or Combined With a BTK Inhibitor

Evidence (use of rituximab maintenance therapy alone or combined with a BTK inhibitor):

- A prospective randomized trial included 299 patients with MCL who underwent chemoimmunotherapy and autologous stem cell transplant (SCT) consolidation. Patients were then randomly assigned to receive either 3 years of rituximab maintenance therapy or observation.[1]

- With a median follow-up of 50.2 months after autologous SCT, the overall survival (OS) rate was 89% (95% confidence interval [CI], 81%–94%) in the rituximab group and 80% (95% CI 72%–88%) in the observation group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.50; 95% CI, 0.26–0.99; P = .04).[1][Level of evidence A1]

- The 4-year event-free survival rate was 79% (95% CI, 70%–86%) in the rituximab group and 61% (95% CI, 51%–70%) in the observation group (P = .001).[1]

- The 4-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate was 83% (95% CI, 73%–88%) in the rituximab group and 64% (95% CI, 55%–73%) in the observation group (P < .001).[1]

- In a prospective trial of 299 patients with untreated MCL, 257 responders received four courses of R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin) and autologous SCT. These patients were then randomly assigned to receive either rituximab maintenance therapy for 3 years or no maintenance therapy.[2]

- The 7-year PFS rate was significantly higher for the rituximab maintenance group at 78.5 % (95% CI, 69.9%–85.0%) versus 47.4% (95% CI, 39.9%–56.3%) for the group that did not receive maintenance therapy (HR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.23–0.56; P < .0001).[2][Level of evidence B1]

- After randomization, with a median follow-up of 7.5 years, the 7-year OS rate in the rituximab maintenance group was not significantly better than in the no-maintenance group (83.2% [95% CI, 74.7%–89.0%] vs. 72.2% [95% CI, 62.9%–79.5%]; HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.37–1.08).

- In a prospective randomized trial, 500 patients aged 60 years or older and not transplant-eligible received induction therapy with R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) or R-FC (rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide) for six to eight cycles. Responders were randomly assigned to receive either rituximab or interferon alfa maintenance therapy until disease relapse.[3]

- With a median follow-up of 8.0 years for the 316 responding patients, the median OS was 9.8 years in the rituximab maintenance group and 7.1 years in the interferon alfa maintenance group (P = .0054).[3][Level of evidence A1]

- As previously described, the TRIANGLE trial (NCT02858258) was a prospective randomized trial that included 870 patients aged 65 years or younger with previously untreated MCL who were transplant-eligible.[4,5] Patients received one of three induction regimens with chemoimmunotherapy (R-CHOP/R-DHAP), with or without ibrutinib and with or without autologous SCT consolidation in the ibrutinib arms. All patients were recommended to have maintenance therapy with at least rituximab or with both rituximab and ibrutinib in the ibrutinib induction therapy arms.[6] Not all patients could tolerate or receive maintenance therapy, and some deferred the recommended maintenance therapy (33%–41% of patients in each group).

- In a retrospective analysis with a median follow-up of 4.0 years, the 4-year PFS rate was 10% to 29% higher for patients who received rituximab maintenance (P ranged from .016 to < .001).[6][Level of evidence C3]

- A retrospective analysis of 1,265 patients aged 65 years and younger evaluated rituximab maintenance therapy after bendamustine and rituximab induction.[7]

- A benefit was seen for rituximab maintenance therapy in time-to-next treatment (HR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.61–2.38; P < .001) and OS (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.19–1.92; P < .001).[7][Level of evidence C3]

- In a prospective randomized trial, 319 patients with follicular lymphoma or MCL received R-FCM (rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone) or FCM (a subsequent analysis confirmed the superiority of R-FCM and all patients received that induction). The 267 patients with disease response were randomly assigned to either rituximab maintenance therapy or observation. Most patients had follicular lymphoma, but 47 patients with disease response had MCL.[8]

- With a median follow-up of 26 months, the 2-year PFS rate was 45% in the rituximab maintenance group and 9% in the observation group (P = .049).[8][Level of evidence B1]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Le Gouill S, Thieblemont C, Oberic L, et al.: Rituximab after Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 377 (13): 1250-1260, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sarkozy C, Thieblemont C, Oberic L, et al.: Long-Term Follow-Up of Rituximab Maintenance in Young Patients With Mantle-Cell Lymphoma Included in the LYMA Trial: A LYSA Study. J Clin Oncol 42 (7): 769-773, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hoster E, Hermine O, et al.: Treatment of Older Patients With Mantle Cell Lymphoma (MCL): Long-Term Follow-Up of the Randomized European MCL Elderly Trial. J Clin Oncol 38 (3): 248-256, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dreyling M, Doorduijn J, Giné E, et al.: Ibrutinib combined with immunochemotherapy with or without autologous stem-cell transplantation versus immunochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in previously untreated patients with mantle cell lymphoma (TRIANGLE): a three-arm, randomised, open-label, phase 3 superiority trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. Lancet 403 (10441): 2293-2306, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dreyling M, Doorduijn JK, Gine E, et al.: Role of autologous stem cell transplantation in the context of ibrutinib-containing first-line treatment in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma: results from the randomized Triangle trial by the European MCL Network. [Abstract] Blood 144 (Suppl 1) A-240, 240-2, 2024.

- Ladetto M, Gutmair K, Doorduijn JK, et al.: Impact of rituximab maintenance added to ibrutinib-containing regimens with and without ASCT in younger, previously untreated MCL patients: an analysis of the Triangle data embedded in the Multiply Project. [Abstract] Blood 144 (Suppl 1): A-237, 2024.

- Martin P, Cohen JB, Wang M, et al.: Treatment Outcomes and Roles of Transplantation and Maintenance Rituximab in Patients With Previously Untreated Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Results From Large Real-World Cohorts. J Clin Oncol 41 (3): 541-554, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Forstpointner R, Unterhalt M, Dreyling M, et al.: Maintenance therapy with rituximab leads to a significant prolongation of response duration after salvage therapy with a combination of rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (R-FCM) in patients with recurring and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: Results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). Blood 108 (13): 4003-8, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Relapsed/Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) whose disease relapses after standard chemoimmunotherapy with or without autologous stem cell transplant (SCT) typically receive a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor. A series of retrospective trials have shown that a BTK inhibitor has superior outcomes compared with repeat chemoimmunotherapy. However, it must be emphasized that some patients do respond well to repeat chemoimmunotherapy (e.g., BR [bendamustine plus rituximab] after R-CHOP [rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone]/R-DHAP [rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin]).[1] Because of the relatively short durations of third and subsequent remissions, consolidation therapy should be considered with allogeneic SCT, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, or clinical trials of bispecific antibodies.[1] Patients with disease relapse who are considered to be at highest risk include those with refractory disease, blastoid morphology, a TP53 pathogenic variant, a Ki-67 level of at least 30%, or progression of disease within 24 months.[1,2]

Treatment for Patients Who Have Not Received a Prior BTK Inhibitor

Evidence (patients who have not received a prior BTK inhibitor):

- An observational cohort study included 385 patients with MCL and disease relapse after 2 years. Patients received BTK inhibitors (usually ibrutinib) or chemoimmunotherapy in a nonrandomized fashion.[3]

- With a median follow-up of 53 months, the median overall survival (OS) was better in patients who received BTK inhibitors (not reached [NR]) than in patients who received chemoimmunotherapy (56 months) (P = .03).[3][Level of evidence C1]

- Acalabrutinib, a selective BTK inhibitor, was studied in a phase II trial of 124 patients with relapsed/refractory MCL. The results of this trial led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve acalabrutinib in 2017, before the approval of ibrutinib.[4]

- With a median follow-up of 15.2 months, the overall response rate was 81% (95% confidence interval [CI], 73%–87%), the complete response rate was 40% (95% CI, 31%–49%), and the 1-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate was 67% (95% CI, 58%–75%).[4][Level of evidence C2]

- Acalabrutinib is a more selective BTK inhibitor with lower rates of atrial fibrillation than ibrutinib (3%–4% vs. 10%–12%).

- Zanubrutinib, a selective BTK inhibitor, was evaluated in a phase II trial of 86 patients with relapsed/refractory MCL.[5]

- With a median follow-up of 35.3 months, the overall response rate was 84%, the complete response rate was 98%, and the median PFS was 33 months (95% CI, 19.4–not estimable [NE]).[5][Level of evidence C2]

- Zanubrutinib is a more selective BTK inhibitor with lower rates of atrial fibrillation than ibrutinib (3%–4% vs. 10%–12%).

- Multiple phase II studies of ibrutinib in patients with relapsed or refractory MCL, including a pooled analysis of 370 patients, showed overall response rates of 66% to 68% and median PFS of 12.5 months to 13.9 months.[6-8] Long-term follow-up of the pooled analysis showed an OS of 61.6 months.[9]

Treatment for Patients Who Have Received a Prior BTK Inhibitor

Evidence (patients who have received a prior BTK inhibitor):

- The reversible, noncovalent BTK inhibitor pirtobrutinib was evaluated in a phase I/II trial of 164 patients with relapsed/refractory MCL.[10]

- With a median follow-up of 12 months, among the 90 patients previously treated with covalent BTK inhibitors (ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, or zanubrutinib), the overall response rate was 57.8% (95% CI, 46.9%–68.1%), including a complete response rate of 20.0%.[10][Level of evidence C3]

- The median duration of response was 2.6 months (95% CI, 7.5–NR).[10][Level of evidence C2]

- Only 3% of patients discontinued therapy because of side effects, which included atrial fibrillation in 1.2% of patients, grade 3 or higher bleeding in 3.7%, dyspnea in 16.5%, diarrhea in 21.3%, and fatigue in 29.9%.

The FDA approved pirtobrutinib for patients who received two prior lines of therapy, including a covalent BTK inhibitor.

- The combination of lenalidomide plus rituximab has been studied in several phase II trials, with an overall response rate of approximately 50% in patients with relapsed MCL.[11-13][Level of evidence C3]

- A prospective phase II trial (ZUMA-2 [NCT02601313]) included 68 patients with relapsed or refractory MCL whose disease failed to respond to BTK inhibitors. Patients received CAR T-cell therapy with brexucabtagene autoleucel, which targets CD19.[14]

- With a median follow-up of 36 months, the objective response rate was 91% (95% CI, 82%–97%), the complete response rate was 68% (95% CI, 55%–78%), the median PFS was 25.8 months (95% CI, 10–48), and the OS was 46.6 months (95% CI, 24.9–NE).[14][Level of evidence C3]

- Grade 3 or higher cytokine release syndrome occurred in 15% of patients, and neurological events occurred in 31% of patients.

- A retrospective evaluation at 16 institutions included 168 patients who received brexucabtagene autoleucel as part of the U.S. Lymphoma CAR-T Consortium. The study showed similar response rates and PFS as the ZUMA-2 trial.[15][Level of evidence C3]

- Patients with relapsed or refractory MCL who had received a median of three prior lines of therapy were enrolled in a phase I/II trial of lisocabtagene maraleucel, an anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy.[16]

- With a median follow-up of 16.1 months, the objective response rate was 83.1% (95% CI, 73.3%–90.5%), and the complete response rate was 72.3% (95% CI, 61.4%–81.6%). The median duration of response was 15.7 months (95% CI, 6.2–24.0).[16][Level of evidence C3]

- Grade 3 or higher cytokine release syndrome occurred in 1% of patients.

- Patients with relapsed or refractory MCL received the CD20 × CD3 bispecific antibody glofitamab in a phase I/II trial.[17]

- With a median follow-up of 19.6 months, 60 patients were evaluable. The overall response rate was 85.0% (95% CI, 73.4%–92.9%), and the complete response rate was 78.3% (95% CI, 65.8%–87.9%).[17][Level of evidence C3]

- The median duration of complete response was 15.4 months (95% CI, 12.7–NE), and the 1-year duration of complete response was 71.0% (95% CI, 56.8%–85.2%).[17][Level of evidence C3]

- Grade 3 or higher cytokine release syndrome occurred in 25% of patients. No grade 3 or higher neurological symptoms were reported.

Treatment for Patients With Highest-Risk Disease

Evidence (treatment for patients with highest-risk disease with blastoid morphology, Ki-67 ≥30%, a TP53 pathogenic variant, or progression of disease <2 years after initial therapy):

- A prospective randomized trial of patients with relapsed or refractory MCL compared ibrutinib plus venetoclax (the BCL-2 inhibitor) versus ibrutinib alone. TP53 pathogenic variants were present in 49% of patients.[18]

- With a median follow-up of 51.2 months, the PFS favored the ibrutinib combination compared with ibrutinib alone (31.9 months vs. 22.1 months; HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.47–0.88; P = .0052). This benefit was seen for the patients with blastoid morphology or TP53 pathogenic variants.[18][Level of evidence B1]

- The complete response rate was 54% in the combination group and 32% in the ibrutinib-alone group (P = .004).[18][Level of evidence C3]

- The median OS was 44.9 months for the ibrutinib-plus-venetoclax arm and 38.6 months for the ibrutinib-alone arm, but this was not statistically significant (P = .346).

- The triple combination of obinutuzumab, ibrutinib, and venetoclax is being studied in clinical trials for the highest-risk patients with relapsed or refractory MCL.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Silkenstedt E, Dreyling M: Treatment of relapsed/refractory MCL. Blood 145 (7): 673-682, 2025. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nadeu F, Martin-Garcia D, Clot G, et al.: Genomic and epigenomic insights into the origin, pathogenesis, and clinical behavior of mantle cell lymphoma subtypes. Blood 136 (12): 1419-1432, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Malinverni C, Bernardelli A, Glimelius I, et al.: Outcomes of younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma experiencing late relapse (>24 months): the LATE-POD study. Blood 144 (9): 1001-1009, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang M, Rule S, Zinzani PL, et al.: Acalabrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (ACE-LY-004): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 391 (10121): 659-667, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Song Y, Zhou K, Zou D, et al.: Zanubrutinib in relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma: long-term efficacy and safety results from a phase 2 study. Blood 139 (21): 3148-3158, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dreyling M, Jurczak W, Jerkeman M, et al.: Ibrutinib versus temsirolimus in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma: an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 387 (10020): 770-8, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Visco C, Di Rocco A, Evangelista A, et al.: Outcomes in first relapsed-refractory younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma: results from the MANTLE-FIRST study. Leukemia 35 (3): 787-795, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rule S, Dreyling M, Goy A, et al.: Outcomes in 370 patients with mantle cell lymphoma treated with ibrutinib: a pooled analysis from three open-label studies. Br J Haematol 179 (3): 430-438, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dreyling M, Goy A, Hess G, et al.: Long-term Outcomes With Ibrutinib Treatment for Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma: A Pooled Analysis of 3 Clinical Trials With Nearly 10 Years of Follow-up. Hemasphere 6 (5): e712, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang ML, Jurczak W, Zinzani PL, et al.: Pirtobrutinib in Covalent Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Pretreated Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 41 (24): 3988-3997, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ruan J, Martin P, Shah B, et al.: Lenalidomide plus Rituximab as Initial Treatment for Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 373 (19): 1835-44, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ruan J, Martin P, Christos P, et al.: Five-year follow-up of lenalidomide plus rituximab as initial treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 132 (19): 2016-2025, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang M, Fayad L, Wagner-Bartak N, et al.: Lenalidomide in combination with rituximab for patients with relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma: a phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Oncol 13 (7): 716-23, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang M, Munoz J, Goy A, et al.: Three-Year Follow-Up of KTE-X19 in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma, Including High-Risk Subgroups, in the ZUMA-2 Study. J Clin Oncol 41 (3): 555-567, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang Y, Jain P, Locke FL, et al.: Brexucabtagene Autoleucel for Relapsed or Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma in Standard-of-Care Practice: Results From the US Lymphoma CAR T Consortium. J Clin Oncol 41 (14): 2594-2606, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang M, Siddiqi T, Gordon LI, et al.: Lisocabtagene Maraleucel in Relapsed/Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Primary Analysis of the Mantle Cell Lymphoma Cohort From TRANSCEND NHL 001, a Phase I Multicenter Seamless Design Study. J Clin Oncol 42 (10): 1146-1157, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Phillips TJ, Carlo-Stella C, Morschhauser F, et al.: Glofitamab in Relapsed/Refractory Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Results From a Phase I/II Study. J Clin Oncol 43 (3): 318-328, 2025. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sawalha Y, Goyal S, Switchenko JM, et al.: A multicenter analysis of the outcomes with venetoclax in patients with relapsed mantle cell lymphoma. Blood Adv 7 (13): 2983-2993, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

Key References for Mantle Cell Lymphoma

These references have been identified by members of the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board as significant in the field of mantle cell lymphoma treatment. This list is provided to inform users of important studies that have helped shape the current understanding of and treatment options for mantle cell lymphoma. Listed after each reference are the sections within this summary where the reference is cited.

- Dreyling M, Doorduijn J, Giné E, et al.: Ibrutinib combined with immunochemotherapy with or without autologous stem-cell transplantation versus immunochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in previously untreated patients with mantle cell lymphoma (TRIANGLE): a three-arm, randomised, open-label, phase 3 superiority trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. Lancet 403 (10441): 2293-2306, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cited in:

- Dreyling M, Doorduijn JK, Gine E, et al.: Role of autologous stem cell transplantation in the context of ibrutinib-containing first-line treatment in younger patients with mantle cell lymphoma: results from the randomized Triangle trial by the European MCL Network. [Abstract] Blood 144 (Suppl 1) A-240, 240-2, 2024.

Cited in:

- Fenske TS, Wang XV, Till BG, et al.: Lack of benefit of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (auto-HCT) in mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) patients (pts) in first complete remission (CR) with undetectable minimal residual disease (uMRD): initial report from the ECOG-ACRIN EA4151 phase 3 randomized trial. [Abstract] Blood 144 (Suppl 2): A-LBA-6, 2024.

Cited in:

- Hermine O, Jiang L, Walewski J, et al.: High-Dose Cytarabine and Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Long-Term Follow-Up of the Randomized Mantle Cell Lymphoma Younger Trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol 41 (3): 479-484, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cited in:

- Le Gouill S, Thieblemont C, Oberic L, et al.: Rituximab after Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Mantle-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 377 (13): 1250-1260, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cited in:

- Lewis DJ, Jerkeman M, Sorrell L, et al.: Ibrutinib-rituximab is superior to rituximab-chemotherapy in previously untreated older mantle cell lymphoma patients: results from the international randomised controlled trial, Enrich. [Abstract] Blood 144 (Suppl 1): A-235, 2024.

Cited in:

Latest Updates to This Summary (05/12/2025)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

This is a new summary.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Mantle Cell Lymphoma Treatment are:

- Eric J. Seifter, MD (Johns Hopkins University)

- Cole H. Sterling, MD (Johns Hopkins University)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Mantle Cell Lymphoma Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/hp/mantle-cell-lymphoma-treatment. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>.

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either “standard” or “under clinical evaluation.” These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s Email Us.