What is targeted therapy?

Targeted therapy is a type of cancer treatment that targets proteins that control how cancer cells grow, divide, and spread. It is the foundation of precision medicine. As researchers learn more about the DNA changes and proteins that drive cancer, they are better able to design treatments that target these proteins.

What are the types of targeted therapy?

Most targeted therapies are either small-molecule drugs or monoclonal antibodies.

Small-molecule drugs are small enough to enter cells easily, so they are used for targets that are inside cells.

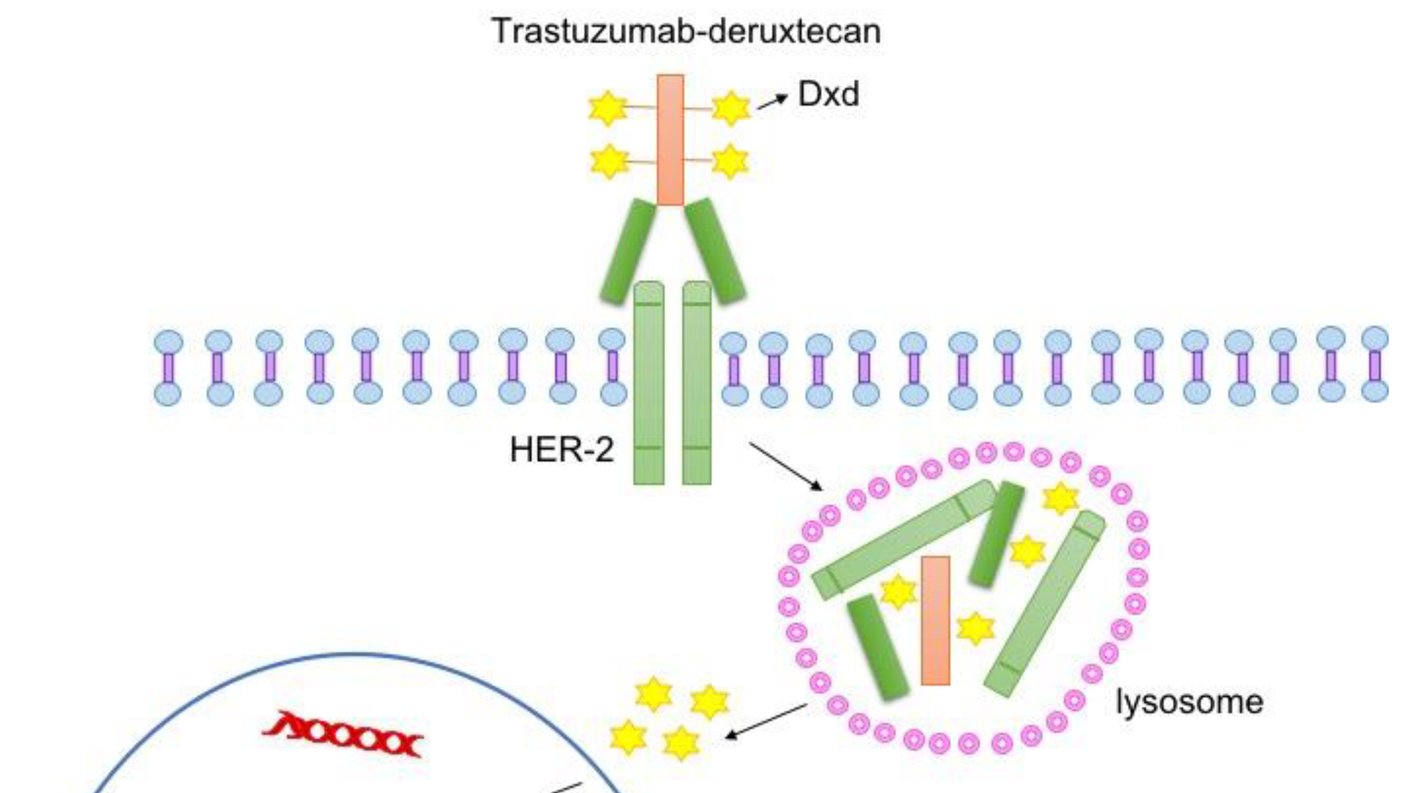

Monoclonal antibodies, also known as therapeutic antibodies, are proteins produced in the lab. These proteins are designed to attach to specific targets found on cancer cells. Some monoclonal antibodies mark cancer cells so that they will be better seen and destroyed by the immune system. Other monoclonal antibodies directly stop cancer cells from growing or cause them to self-destruct. Still others carry toxins to cancer cells. Learn more about monoclonal antibodies.

Who is treated with targeted therapy?

For some types of cancer, such as chronic myelogenous leukemia (also known as CML), most people with that cancer will have a target for a certain drug, so they can be treated with that drug. But most of the time, your tumor will need to be tested to see if it contains targets for which there is a drug.

Testing your cancer for targets that could help choose your treatment is called biomarker testing. See Biomarker Testing for Cancer Treatment for more information.

You may need to have a biopsy for biomarker testing. A biopsy is a procedure in which your doctor removes a piece of the tumor for testing. There are some risks to having a biopsy. These risks vary depending on the size of the tumor and where it is located. Your doctor will explain the risks of having a biopsy for your type of tumor.

Look up your type of cancer on the list of targeted therapy drugs approved to treat specific cancers to learn more about drugs that may be an option for you.

How does targeted therapy work against cancer?

Most types of targeted therapy help treat cancer by interfering with specific proteins that help tumors grow and spread throughout the body. This is different from chemotherapy, which often kills all cells that grow and divide quickly. The following explains the different ways that targeted therapy treats cancer.

- Help the immune system destroy cancer cells. One reason that cancer cells thrive is because they can hide from your immune system. Certain targeted therapies can mark cancer cells so it is easier for the immune system to find and destroy them. Other targeted therapies help boost your immune system to work better against cancer. Learn more about immunotherapy to treat cancer.

- Stop cancer cells from growing by interrupting signals that cause them to grow and divide without order. Healthy cells in your body usually divide to make new cells only when they receive strong signals to do so. These signals bind to proteins on the cell surface, telling the cells to divide. This process helps new cells form only as your body needs them. But, some cancer cells have changes in the proteins on their surface that tell them to divide whether or not signals are present. Some targeted therapies interfere with these proteins, preventing them from telling the cells to divide. This process helps slow cancer’s uncontrolled growth.

- Stop signals that help form blood vessels. To grow beyond a certain size, tumors need to form new blood vessels in a process called angiogenesis. The tumor sends signals that start angiogenesis. Some targeted therapies called angiogenesis inhibitors interfere with these signals to prevent a blood supply from forming. Without a blood supply, tumors stay small. Or, if a tumor already has a blood supply, these treatments can cause blood vessels to die, which causes the tumor to shrink. Learn more about angiogenesis inhibitors.

- Deliver cell-killing substances to cancer cells. Some monoclonal antibodies are combined with cell-killing substances such as toxins, chemotherapy drugs, or radiation. Once these monoclonal antibodies attach to targets on the surface of cancer cells, the cells take up the cell-killing substances, causing them to die. Cells that don’t have the target will not be harmed.

- Cause cancer cell death. Healthy cells die in an orderly manner when they become damaged or are no longer needed. But, cancer cells have ways of avoiding this dying process. Some targeted therapies can cause cancer cells to go through this process of cell death, which is called apoptosis.

- Starve cancer of hormones it needs to grow. Some breast and prostate cancers require certain hormones to grow. Hormone therapies are a type of targeted therapy that can work in two ways. Some hormone therapies prevent your body from making specific hormones. Others prevent the hormones from acting on your cells, including cancer cells. Learn more about hormone therapy for prostate cancer and hormone therapy for breast cancer.

Are there drawbacks to targeted therapy?

Targeted therapy does have some drawbacks.

- Cancer cells can become resistant to targeted therapy. Resistance can happen when the target itself changes and the targeted therapy is not able to interact with it. Or it can happen when cancer cells find new ways to grow that do not depend on the target. Because of resistance, targeted therapy may work best when used with more than one type of targeted therapy or with other cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiation.

- Drugs for some targets are hard to develop. Reasons include the target’s structure, the target’s function in the cell, or both.

What are the side effects of targeted therapy?

When targeted therapy was first developed, scientists thought that it would be less toxic than chemotherapy. But they have learned that targeted therapy can also cause serious side effects. The side effects that you may have depends on the type of targeted therapy you receive and how your body reacts to it.

The most common side effects of targeted therapy include diarrhea and liver problems. Other side effects might include

- problems with blood clotting and wound healing

- high blood pressure

- fatigue

- mouth sores

- nail changes

- the loss of hair color

- skin problems, which might include rash or dry skin

Very rarely, a hole might form through the wall of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large bowel, rectum, or gallbladder.

There are medicines for many of these side effects. These medicines may prevent the side effects from happening or treat them once they occur.

Most side effects of targeted therapy go away after treatment ends.

Learn more about side effects caused by cancer treatment and ways to manage them.

What can I expect when having targeted therapy?

How is targeted therapy given?

Small-molecule drugs are pills or capsules that you can swallow.

Monoclonal antibodies are usually given through a needle in a blood vein.

Where do I go for targeted therapy?

Where you go for treatment depends on which drugs you are getting and how they are given. You may take targeted therapy at home. Or you may receive targeted therapy in a doctor’s office, clinic, or outpatient unit in a hospital. Outpatient means you do not spend the night in the hospital.

How often will I receive targeted therapy?

How often and how long you receive targeted therapy depends on

- your type of cancer and how advanced it is

- the type of targeted therapy

- how your body reacts to treatment

You may have treatment every day, every week, or every month. Some targeted therapies are given in cycles. A cycle is a period of treatment followed by a period of rest. The rest period gives your body a chance to recover and build new healthy cells.

How will targeted therapy affect me?

Targeted therapy affects people in different ways. How you feel depends on how healthy you are before treatment, your type of cancer, how advanced it is, the kind of targeted therapy you are getting, and the dose. Doctors and nurses cannot know for certain how you will feel during treatment.

How will I know whether targeted therapy is working?

While you are receiving targeted therapy, you will see your doctor often. He or she will give you physical exams and ask you how you feel. You will have medical tests, such as blood tests, x-rays, and different types of scans. These regular visits and tests will help the doctor know whether the treatment is working.

Where can I find out about clinical trials of targeted therapy?

Clinical trials of targeted therapy and other cancer treatments take place in cities and towns across the United States and throughout the world. They take place in doctors' offices, cancer centers, medical centers, community hospitals and clinics, and veteran and military hospitals.

To find clinical trials of targeted therapy use this advanced search form. Under "Keywords/Phrases," type "targeted therapy." Under "Trial Type," select the box for "Treatment" trials.

If you need help finding trials, contact the Cancer Information Service, NCI's contact center.