Many Ovarian Cancers May Start in Fallopian Tubes, Study Finds

, by NCI Staff

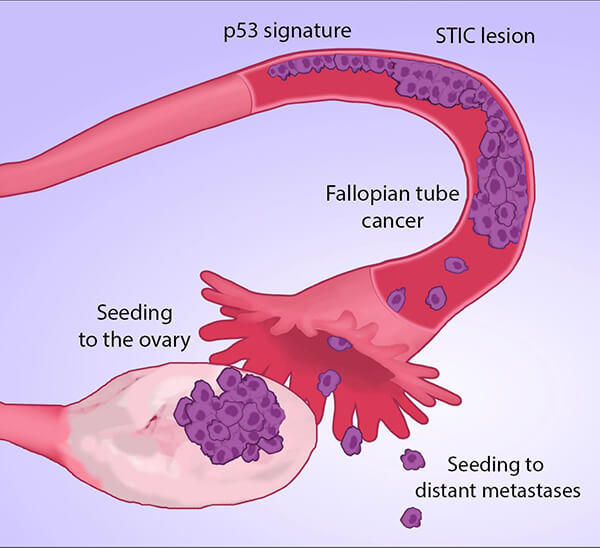

Findings from a new study provide additional evidence that the most common type of ovarian cancer may originate in the fallopian tubes. Researchers also found that there is a window of several years between the development of abnormal cells, or lesions, in the fallopian tubes and the start of ovarian cancer.

The findings “have significant implications for the prevention, early detection, and therapeutic intervention of this disease,” the study investigators wrote.

In the study, published October 23 in Nature Communications, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute analyzed multiple tumor samples from nine patients with high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas (HGSOC), the subtype that accounts for approximately 75% of ovarian cancers.

The researchers found that most of the genetic alterations seen in ovarian tumors in these patients were present in lesions that had formed years earlier in their fallopian tubes. This finding is important, they wrote, because it could potentially help to enable earlier detection of the disease. Currently, about 70% of women with HGSOC are diagnosed with advanced stage disease.

Tracing the Origins of HGSOC

Studies conducted more than a decade ago provided evidence that HGSOCs may not arise from cells of the ovary. Instead, the studies suggested that lesions found in the fallopian tubes, called serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas (STICs), might be precursors for most HGSOCs, said Christina Annunziata, M.D., Ph.D., clinical director of the Women’s Malignancies Branch of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research.

Those earlier studies identified STIC lesions in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations who’d had prophylactic surgery to remove their fallopian tubes and ovaries to reduce their cancer risk, suggesting that the lesions could be precursors to ovarian cancer.

The new study, along with findings from another molecular analysis of STICs published in the same issue of the journal, provide additional evidence that HGSOCs originate from these fallopian tube lesions, Dr. Annunziata said, regardless of whether women have BRCA mutations.

“We now have a molecular basis to support the original finding,” she explained. “It’s very exciting.”

In the first study, researchers used genomic sequencing to profile all the expressed genes in the genomes of tissue samples from five women with HGSOC who also had STIC lesions and fallopian tube cancer.

They also analyzed STIC lesions from four additional patients, three of whom had undergone prophylactic surgery to remove their fallopian tubes and ovaries because of BRCA mutations. The fourth patient had fallopian tubes and ovaries removed as well as a hysterectomy because of a pelvic mass.

Using a mathematical model, the researchers then estimated that the average time between the development of the STIC lesions and ovarian cancer was 6.5 years. They found that while the lesions were slower to develop, “in patients with metastatic lesions, the time between the initiation of the ovarian carcinoma and development of metastases appears to have been rapid (average 2 years),” they wrote.

This may explain why most cases of HGSOC are in advanced stages at diagnosis and has implications for early detection of the disease, the researchers wrote.

Impact on Ovarian Cancer Prevention

Although the study findings are relevant for the most common type of ovarian cancer, high-grade serous cancers, Dr. Annunziata commented, “[it’s important to note that] around 30% of ovarian cancers might not originate in the fallopian tubes.”

Ovarian cancer subtypes other than HGSOC, such as low-grade serous cancers and endometrial cancers, are believed to arise from cells of the ovary itself, “but we don’t have these types of extensive molecular analyses to prove that,” she said.

This study was also based on a small sample size, the research team acknowledged.

But “if studies in larger groups of women confirm our finding that the fallopian tubes are the site of origin of most ovarian cancer, then this could result in a major change in the way we manage this disease for patients at risk,” said lead author Victor Velculescu, M.D., Ph.D., co-director of Cancer Biology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, in a press release.

Dr. Annunziata agreed that further studies need to be done to better understand the studies’ implications.

For example, clinical trials could be done to determine whether removing the fallopian tubes, and not the ovaries, in women who are at high risk for HGSOC is sufficient to reduce their risk of the disease, she said. Removing ovaries causes surgical menopause, which can greatly affect quality of life. Research has also shown that preservation of ovaries provides long-term health benefits by lowering the risk of heart disease and other illnesses.

Trials in the United States and the Netherlands are currently underway to see if removing fallopian tubes and delaying the removal of ovaries should be considered in women with BRCA mutations who are at high risk of developing ovarian cancer.

The study authors wrote that their findings have implications for women who are not carriers of BRCA mutations as well. In fact, other trials are looking at the safety and feasibility of removing fallopian tubes during other gynecologic surgeries, such as hysterectomy, to prevent ovarian cancer in women who are or are not at high risk of developing it.