Study Identifies Potential Cause of Hearing Loss from Cisplatin

, by NCI Staff

Results from a new study may explain why many patients treated with the chemotherapy drug cisplatin develop lasting hearing loss.

Researchers found that, in both mice and humans, cisplatin can be found in the cochlea—the part of the inner ear that enables hearing—months and even years after treatment. By contrast, the drug is eliminated from most organs in the body within days to weeks after being administered.

The study, led by researchers from the National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), part of the National Institutes of Health, was published November 21 in Nature Communications.

Cisplatin, a platinum-based chemotherapy drug, is commonly used for the treatment of many cancers, including bladder, ovarian, and testicular cancers. But cisplatin and other similar platinum-containing drugs can damage the cochlea, leaving 40%–80% of adults, and at least 50% of children, with significant permanent hearing loss, a condition that can greatly affect quality of life.

“This study starts to explain why patients who receive the drug sustain hearing loss,” said Percy Ivy, M.D., associate chief of NCI’s Investigational Drug Branch, who was not involved in the study. “This is very important, because as we come to understand how cisplatin-related hearing loss occurs, over time we may figure out a way to block it, or at least diminish its effects.”

A New Approach to Researching Cisplatin-Induced Hearing Loss

The new study differs from previous research because it is a comprehensive look at the pharmacokinetics, or concentration, of the drug in the inner ear, explained study investigator Andrew Breglio, of NIDCD.

The research team primarily used a technique called inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) to quantify the amount of platinum left in inner ear tissue following cisplatin treatment in mice.

Lisa Cunningham, Ph.D., of NIDCD, who led the research team, noted that instead of using one high dose of cisplatin with mice as other studies have, they developed a treatment protocol like those used in everyday care, in which the drug is given in cycles.

Testing done following each cisplatin cycle showed increasingly progressive hearing loss in the mice. The researchers also measured platinum levels in various organs throughout the drug cycles and found that, whereas other organs eliminated the drug relatively quickly, the cochlea retained the cisplatin, showing no significant loss of platinum 60 days after the last administration of the drug.

The researchers also conducted postmortem analysis of inner ear tissue of human patients who had received cisplatin, and found that platinum was retained in cochleae at least 18 months after the last treatment. In addition, they found that in the cochlea of one pediatric patient (the only one available for study), significantly more platinum was retained than in adult patients, consistent with the fact that children’s ears are known to be more susceptible to cisplatin-induced hearing loss.

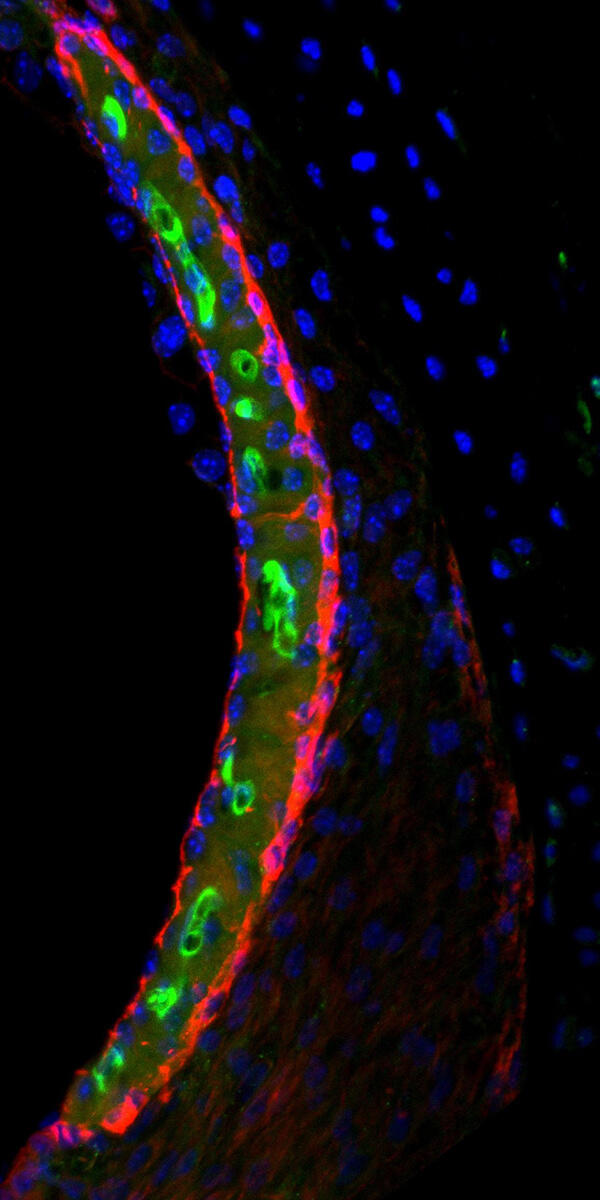

In both the mouse model and in studies of human tissue, the researchers determined that the platinum accumulates in a part of the cochlea called the stria vascularis, which, Breglio explained, regulates the makeup of the fluid that bathes the sensory hair cells in the ear “and is critical to their proper function.”

This lengthy retention in the cochlea could explain why this drug is damaging the inner ear, Breglio said. Furthermore, these findings, demonstrating the accumulation of the drug and identifying where it is retained, mean that future studies need to “look beyond hair cells” to explain cisplatin-induced hearing loss, the researchers wrote.

Findings That Could Lead to Hearing Loss Treatment and Prevention

The finding that cisplatin is retained in the cochlea indefinitely is important for patient care, Dr. Ivy said.

Hearing loss from cisplatin “is not a static injury, it doesn’t stay the same. It can progress over time and it can occur late,” she added. “That suggests that a long-term survivor needs ongoing monitoring of their hearing.”

She said it will be up to practitioners to continue this monitoring and to rapidly intervene with devices that assist in hearing, such as hearing aids.

Hearing loss can have a particularly negative impact on children, she said.

“If adults develop hearing loss, they’re more acutely aware of it, and are more likely to seek assistance, whereas younger children who develop hearing loss might not notice it as much or be unable to explain the problem,” she explained. “Since they can’t hear very well, they may have trouble paying attention and that could be misconceived as a learning disability or a behavior problem. And yet, if they get the appropriate intervention, they perform at the same level they did prior to receiving platinum.”

This is why researchers on Dr. Cunningham’s team are trying to find ways to block cisplatin from entering the inner ear. They are looking at the cellular mechanism by which cisplatin is taken up by the cells of the stria vascularis to find ways to block uptake, as well as identify drugs that might “target cisplatin itself, and bind it or sequester it” before it can get into the inner ear, Breglio said.

“[Cisplatin] is one of the most widely used anticancer drugs on the planet, and it’s saving a lot of lives,” Dr. Cunningham said. But the hearing loss is permanent. “So these patients are surviving and they have this hearing loss for the rest of their lives. What we’d like to be able to do is develop a therapy that will allow patients to take the life-saving drug, but preserve their hearing.”