Experimental Drug Prevents Doxorubicin from Harming the Heart

, by NCI Staff

The chemotherapy drug doxorubicin is used to treat many types of cancer, but some patients who receive the drug develop heart problems. Using new insights into how doxorubicin damages the heart, researchers have identified an experimental drug that may help protect the heart.

In mice, the experimental drug, called BAI1, prevented doxorubicin-induced heart damage, and did so without interfering with doxorubicin’s ability to kill cancer cells, researchers reported in Nature Cancer on March 2.

BAI1 binds to a protein called BAX, which, the researchers found, is required for the death of heart cells in mice treated with doxorubicin. When activated by doxorubicin, BAX initiates two biological processes that cause heart cells to die: apoptosis and necrosis. BAI1, the research team showed, blocks both.

“With BAX, we have a single target for blocking both types of cell death stemming from the use of doxorubicin,” said Richard Kitsis, M.D., of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, who co-led the study. “And doxorubicin still retains the desired effect of killing cancer cells.”

Using mouse models of breast cancer and leukemia, the researchers showed that treating mice with doxorubicin plus BAI1 shrank tumors without harming the heart, whereas doxorubicin alone shrank tumors but led to heart damage.

“Many cancer drugs can damage the heart,” said Javid Moslehi, M.D., who directs the Cardio-Oncology Program at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center and was not involved in the research. But, he added, “doxorubicin is notorious” for causing cardiac side effects that, in some patients, lead to eventual heart failure.

This new study, Dr. Moslehi continued, identifies a pathway that’s important for controlling cell death in heart cells. “And, just as important, it shows that a drug that inhibits the pathway doesn’t take away doxorubicin’s ability to kill cancer cells.”

Dr. Kitsis and Evripidis Gavathiotis, Ph.D., also of Albert Einstein College of Medicine and co-leader of the new study, are planning a clinical trial to test the inhibition of BAX in patients receiving doxorubicin, either with BAI1 or a similar drug, known as an analog.

Treatments for Cancer Patients and Survivors

Certain patients are at increased risk of doxorubicin-induced heart damage. They include older adults, especially those with existing heart disease or risk factors for heart disease, and children with difficult-to-treat cancers like sarcoma, who may need high doses of the drug.

Another group at risk are those whose cancer has returned and who were previously treated with doxorubicin and other therapies that may harm the heart, such as radiation therapy and certain targeted therapies.

“Cancer survivors are living longer, and some of these survivors will die of heart disease related to prior treatment with doxorubicin, so this approach might be a way to prevent some of those deaths,” said Dr. Kitsis.

Using New Insights into How Heart Damage Occurs

Although the cardiac side effects of doxorubicin have been known for decades, the search for ways to reduce these side effects has been slowed by limited knowledge about how that damage happens.

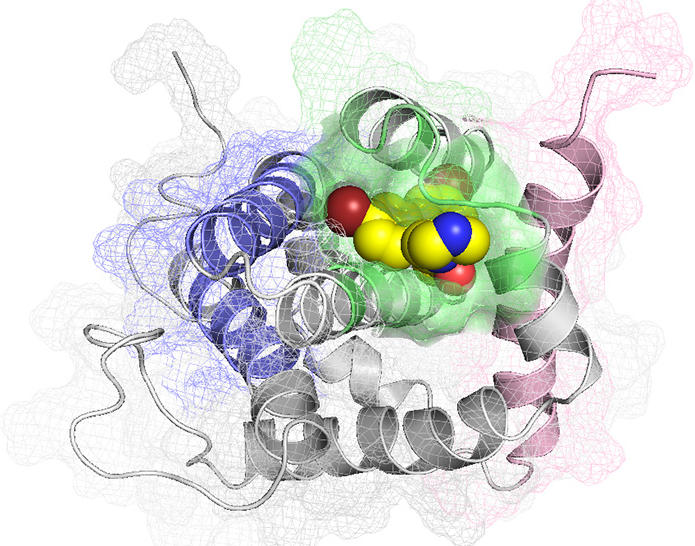

The new study builds on insights from the investigators’ earlier research on cardiac damage and the basic biology of BAX. For example, a previous study led by Dr. Gavathiotis described how the shape or “conformation” of BAX changes and helps the protein relocate to mitochondria, where it can initiate apoptosis and necrosis.

And last year the researchers reported that small molecules, including the compound now known as BAI1, can bind to BAX and prevent its activation and migration to the mitochondria.

“Our current study shows that BAI1 works by preventing BAX from converting to its active and lethal form,” said Dr. Gavathiotis. “BAI1 is interesting because it’s the first compound that binds to BAX and inhibits both apoptosis and necrosis.”

Testing a BAX Inhibitor

In this current study, the researchers tested the effects of BAI1 on cells and animal models, including mice that had normal levels of BAX protein and those that had been genetically altered to lack the protein.

When they treated mice with doxorubicin, those mice with normal BAX levels developed heart failure, which was accompanied by apoptotic and necrotic cardiac cell death. This is similar to the changes experienced by some patients who are treated with doxorubicin, Dr. Kitsis noted.

None of these changes occurred in mice that were genetically altered to not produce BAX. “Thus, while doxorubicin impacts multiple processes in heart muscle cells, the results show that the end result—cardiac cell death and heart failure—is highly dependent on BAX,” he said.

Further experiments using two mouse models of breast cancer and one of leukemia showed that BAI1 did not compromise doxorubicin’s ability to kill cancer cells. One potential reason for that finding, the researchers showed, was that, in the mice, BAX levels were much higher in cancer cells than they were in the heart.

Potential Implications for Other Treatments

If BAX inhibitors are shown to prevent or limit doxorubicin-induced heart damage in clinical trials, "a drug like BAI1 may allow oncologists to use higher doses of doxorubicin than is currently possible or doxorubicin in combination with other cardiotoxic cancer agents without causing heart failure," Dr. Kitsis said.

In future studies, the approach of inhibiting BAX could be tested using other cancer agents, including targeted therapies, that may also damage the heart through mechanisms that depend on BAX, according to the study authors.

But the priority is to test BAI1 or an analog in patients with cancer who are being treated with doxorubicin, Dr. Kitsis said.

“It’s natural to get excited about promising preclinical results, but we won’t know how this approach will work in people until it is tested in a clinical trial,” said Dr. Moslehi.

Nonetheless, he added, “This is a good basic research study, and the field of cardio-oncology needs more studies that can reveal mechanisms underlying treatment-induced heart damage.”