SBRT Emerging as an Important Treatment for Early-Stage Kidney Cancer

, by Carmen Phillips

For some people with kidney cancer, a treatment called stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) appears to be a highly effective treatment when surgery isn’t an option, according to new findings from a clinical trial.

The trial, called FASTRACK II, only included people with a single tumor in their kidney—called localized kidney cancer—who were not able to undergo surgery to have it removed, mostly because of other health problems.

All 70 people in the trial had their tumors treated with SBRT, and over the next few years none had any evidence that their tumors had come back and none died of their disease. Only one patient had evidence of the cancer returning somewhere else in the body 3 years after receiving the treatment.

Treatment with SBRT also appeared to be safe—in particular, it had no notable impact on patients’ kidney function, according to results reported on October 1 at the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) annual meeting.

The results of FASTRACK II “are quite exceptional and unexpected,” said the trial’s lead investigator, Shankar Siva, M.B.B.S., Ph.D., of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Australia.

The only other treatment options for people with localized kidney cancer who cannot have surgery are “ablation” techniques that kill tumors with extreme heat or cold, or routine monitoring of the cancer to see if it gets worse, Dr. Siva explained during a press briefing at the ASTRO meeting.

But ablation doesn’t work well for larger tumors (larger than 4 cm), which most patients in the trial had, he said. And doctors may advise routine monitoring, often called surveillance, for small tumors.

Once surgery has been ruled out, people with larger tumors “don’t have another curative treatment option,” he said. So particularly for people with larger tumors who can’t have surgery, he continued, the trial results suggest that SBRT should be the treatment of choice.

Other experts agreed.

Widely accepted cancer treatment guidelines already include SBRT as an option for patients who can’t undergo surgery, explained said Rohann Correa, M.D., of the London Regional Cancer Program in Ontario, Canada, during the briefing.

These trial results “only bolster the quality of the evidence that backs that recommendation,” Dr. Correa said.

When surgery isn’t possible, what are the options?

The most common form of kidney cancer is called renal cell carcinoma. In most people diagnosed with this form of kidney cancer, the disease is a single tumor, ranging in size from less than 4 centimeters (about 1.5 inches wide) and up to about 10 centimeters (about 4 inches wide).

Surgery is the most common treatment for localized kidney cancer, explained Saby George, M.D., of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York, who specializes in treating kidney cancer. Surgery can cure the disease in many patients, Dr. George said.

For smaller tumors, depending on factors such as their location, surgery typically involves removing only the part of the kidney that includes the tumor, called a partial nephrectomy. Otherwise, the entire kidney is removed, known as a radical nephrectomy.

But a small percentage of people diagnosed with localized kidney cancer can’t have surgery. Most often that’s because they have other health conditions—such as obesity, heart disease, or chronic kidney disease—that make surgery dangerous or not feasible.

Starting in the early 2000s, SBRT emerged as a possible alternative for people who can’t undergo surgery.

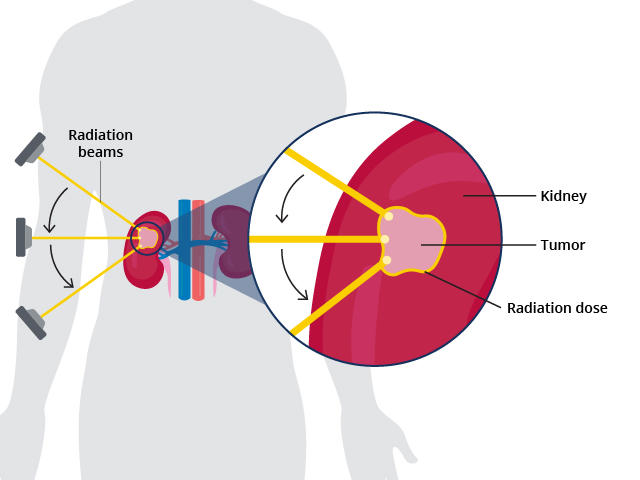

The technique requires patients to undergo several imaging procedures that allow doctors to precisely map the tumor in the kidney. Based on that mapping, radiation oncologists then develop a treatment plan that allows them to target multiple radiation beams directly to the tumor. The entire procedure is noninvasive.

Killing tumors with extreme heat or cold, called thermal ablation, can work well for smaller tumors, Dr. Siva said. But unlike SBRT, he noted, ablation is invasive, requiring a probe to be inserted through an opening in the skin into the tumor. And neither form of ablation is very effective against larger tumors or when the tumor is deeper in the kidney.

Smaller clinical trials of SBRT to treat people who aren’t candidates for surgery had largely positive results, but a larger trial conducted at multiple centers—which can provide more definitive evidence of how effective a treatment really is—had yet to be performed.

Dr. Siva and colleagues launched the FASTRACK II trial with the goal of filling that gap.

Controlling kidney tumors and no safety concerns

The FASTRACK II trial was predominantly conducted in Australia. The average age of the 70 people who participated was 77, and many were clinically obese and had other medical conditions. About one third had tumors smaller than 4 centimeters and, with one exception, the remainder had tumors between 4 and 9 centimeters (see sidebar).

“The tumors [in the trial] were larger and more complex than what could be reasonably treated with thermal ablation,” Dr. Siva said.

Participants were treated at one of seven hospitals and measures were put in place to ensure that patients received the most effective doses of radiation and the highest quality of treatment, he explained.

Participants with smaller tumors only had to undergo a single treatment, Dr. Siva said. “It might last an hour, and they could drive themselves to and from the appointment,” he said. Those with larger tumors had three treatments over 2 weeks.

Trial participants were followed for a median of 43 months. No participants had their kidney tumor come back or died from cancer during the trial (several did die from other causes not related to the treatment).

At 5 years after the SBRT treatment, only two participants had evidence that their cancer had returned elsewhere in the body.

A side effect of particular concern with SBRT or ablation is a decrease in kidney function. Particularly for people with underlying kidney disease, significant loss of kidney function can mean having to go on dialysis for the remainder of their lives.

Nearly all patients in the trial had decreased kidney function when they began treatment. But, with one exception, all had only limited further reductions. One person did have to go on dialysis, Dr. Siva said, but they had a particularly large tumor and enrolled in the trial with poor kidney function.

Next trial up: SBRT versus surgery?

The FASTRACK II trial “represents an important milestone,” said Dr. Correa, who specializes in treatments like SBRT. The results, he continued, show that SBRT should be strongly considered for people with localized kidney cancer who can’t undergo surgery.

In addition to being noninvasive, SBRT’s convenience, and the fact that patients don’t have to stop taking most other medications to receive it, all make it very attractive.

“These are factors that are important to my patients,” he said during the press briefing.

Dr. George agreed that the findings should influence patient care. “The results are impressive,” he said.

When it comes to people whose tumors are 7 centimeters or less, he continued, the trial results “are already beating the surgical numbers” in terms of outcomes such as keeping tumors from returning and impact on kidney function.

He cautioned, however, that although larger than earlier trials, FASTRACK II was still relatively small and that SBRT was not directly compared against other treatment options, the latter of which is typically considered to be the gold standard for determining a treatment’s effectiveness. So more robust studies need to be performed, he said.

It will be important, Dr. George continued, to see more data about the treatment’s safety, including whether there is any long-term damage to nearby organs.

He also agreed with Dr. Siva that a clinical trial comparing SBRT against surgery should be done.

Dr. Siva said he and his colleagues are currently designing such a trial, which would most likely involve cancer centers from around the world.

There are also potential opportunities for SBRT in treating people with kidney cancer that has spread, or metastasized, to other parts of the body, Dr. George said.

For example, he continued, many people with metastatic kidney cancer are now being treated with immunotherapy. Some of these patients may have a tumor in their kidney that could be removed with surgery, but the surgery could cause complications that affect their ability to receive immunotherapy or other treatments.

So, it would be good to conduct studies to see if SBRT could be an option in these cases, he said.