Trial Results Confirm Effectiveness of Atezolizumab Against a Rare Sarcoma

, by Linda Wang

Faithanne Hill was only 11 when she was diagnosed with alveolar soft part sarcoma, an extremely rare soft tissue cancer that is diagnosed in only about 80 people (mostly adolescents and young adults) in the United States each year. Now 21, the first-year college student has been through a lot over the past decade.

In addition to going through the usual teenage experiences in her home country of Trinidad, she’s also had a half dozen or so surgeries at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD, to remove new tumors that seemed to develop out of nowhere—a common occurrence for this cancer.

So far, the surgeries have kept her disease at bay. But Faithanne said she worries that, one day, surgery won’t work anymore, and she will have few treatment options. Chemotherapy generally doesn’t work for alveolar soft part sarcoma.

Several years ago, Faithanne joined a clinical trial to see whether the immunotherapy drug atezolizumab (Tecentriq) could help shrink her tumors. Results of that study, which included 52 people with advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma, were published September 7 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

All 52 people in the trial were treated with atezolizumab. Of these, 19 (37%) saw their tumors shrink by at least 30% (partial response), and one person’s tumors disappeared altogether (complete response). Patients who were treated for more than 2 years were given the option to take a treatment break.

Seven patients chose this option and, so far, none have had evidence on imaging scans that their tumors are growing again.

In December 2022, based on an earlier review of this study and its findings, the Food and Drug Administration approved atezolizumab for adults and children 2 years and older with advanced alveolar soft part sarcoma. This is the first drug ever approved for this rare disease.

“What this trial has shown is that you can manage alveolar soft part sarcoma by managing the immune system,” said Alice Chen, M.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis (DCTD), who led the study. “It’s also possible that patients may be able to stop treatment after a period of time. For these young people, that may make a huge difference.”

“This study is a tour de force,” said Christian F. Meyer, M.D., Ph.D., a sarcoma specialist at Johns Hopkins Medicine, who was not part of the trial. “Eight years ago, we were not thinking about immune therapies for alveolar soft part sarcoma, and here we are now with a drug approval based largely on this work. This study also provides hope that trials in rare cancers are possible and can lead to really pivotal results.”

Although Faithanne had to leave the trial early to undergo a major surgery for her cancer, she said she’s relieved that there is now an approved treatment if her cancer progresses.

“I’m really happy that they’ve found something that works,” she said.

Using immunotherapy to control a rare disease

Alveolar soft part sarcoma, or ASPS, is a type of soft-tissue sarcoma that can form in muscle, bone, nerves, and fat. ASPS grows more slowly than many other sarcomas and generally develops in younger people.

It often starts as a painless lump in the leg, arm, head, or neck but can spread to other parts of the body, such as the lungs. It can also spread to the brain, which is not often seen with other soft tissue sarcomas.

Patients usually have surgery to remove ASPS tumors, often followed by radiation to kill any remaining cancer cells. But the tumors often come back, requiring many subsequent surgeries.

Once the disease spreads beyond where it originally developed, and if the disease spreads to locations where it cannot be surgically removed, there has been no effective treatment for the disease. Less than 50% of people with ASPS that has spread and cannot be treated surgically survive 5 years after diagnosis.

With chemotherapy largely ineffective against ASPS, researchers have been exploring newer treatments, including targeted therapies, but with little success. One targeted therapy, pazopanib (Votrient), has been approved for soft tissue sarcomas in general, but it’s unclear how well it works against ASPS.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as atezolizumab have also shown hints of promise. In a small clinical trial, tumors shrank in 6 of 11 people with ASPS treated with a combination of the immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and the targeted drug axitinib (Inlyta).

Atezolizumab, which is approved to treat several other types of cancer, had also shown some effectiveness, anecdotally, in several people with this cancer.

Based on these anecdotal findings, Dr. Chen and her colleagues at NCI wanted to see whether they could achieve similar results under the more rigorous standards of a clinical trial. Genentech, which manufactures atezolizumab, provided the drug for the trial under a special research agreement with NCI.

Responses with atezolizumab that appear to last

In the phase 2 trial, 52 adults and children with advanced ASPS who had not previously been treated with checkpoint inhibitors were given an infusion of atezolizumab every 21 days.

Among the 37% of participants whose tumors responded to the treatment, the lone complete response occurred about a year after the person began treatment. Of the remaining 33 participants, 30 had stable disease—that is, their cancer didn’t get better or worse. Typically, without treatment, ASPS tumors will continue to grow, Dr. Chen said.

Most people who responded to treatment began to see tumor shrinkage within the first 3 to 5 months. For three patients, it took more than a year of atezolizumab infusions before their tumors began to shrink.

Side effects of the treatment were mostly mild and included anemia, diarrhea, rash, and pain. Nobody discontinued treatment because of side effects.

After more than 2 years of treatment, seven people opted to take a 2-year break from treatment. Two of the 7 have completed the break without needing to resume atezolizumab at any point, so they have left the study.

The five others are still completing their treatment break. So far, none of the 7 patients have experienced a progression or return of their cancer.

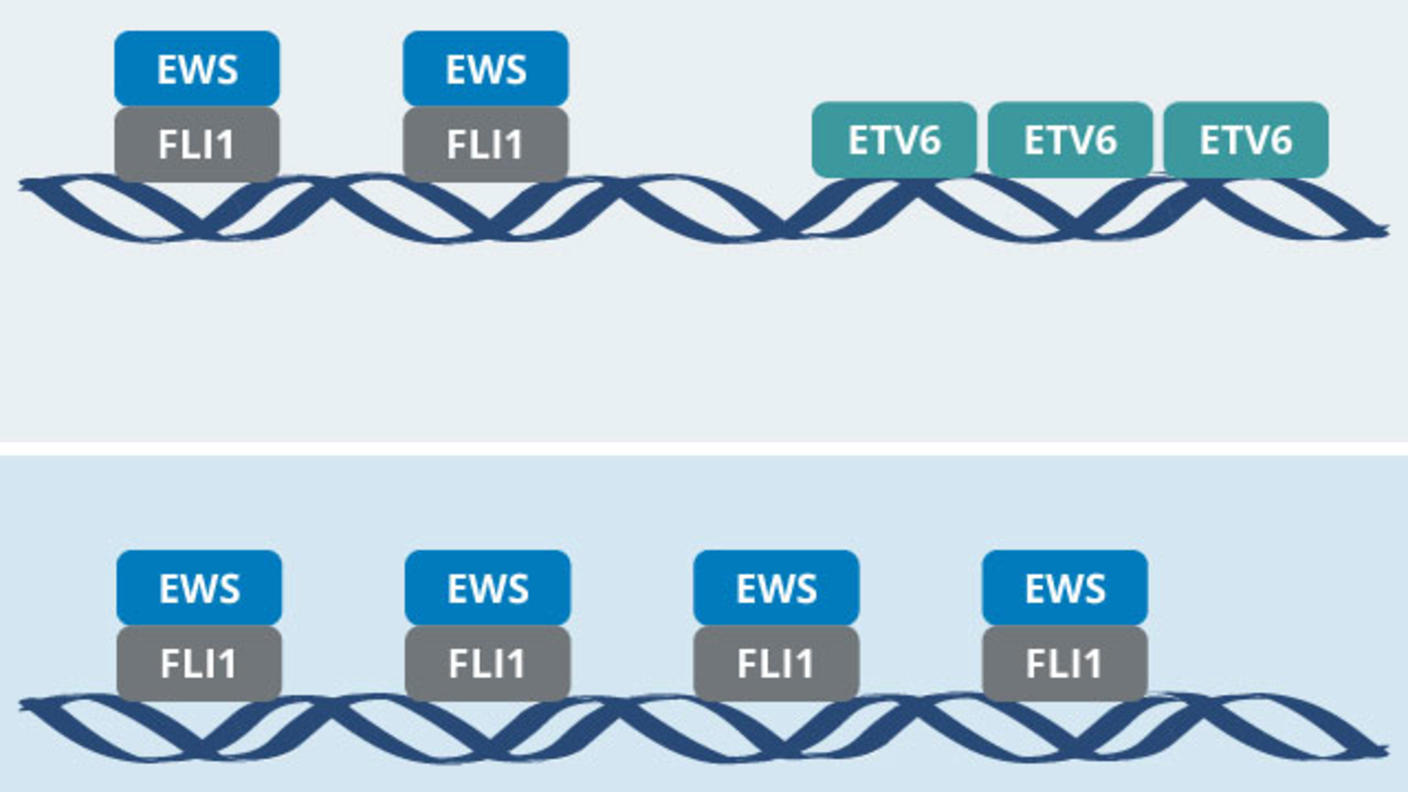

Understanding how atezolizumab works in ASPS

Elad Sharon, M.D., of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, who co-led the study while he was at NCI, pointed out that atezolizumab has not been shown to be as effective in other sarcomas as it is for ASPS.

“The immune system is actually functioning in [ASPS] patients in different ways than it does in people with other sarcomas,” Dr. Sharon said. One possible difference, he continued, is that ASPS tumors may contain different cancer-related proteins that, with help from atezolizumab, the immune system is more likely to recognize and attack.

The research team wanted to better understand why the treatment worked in some patients and not others, and why some tumors only began to shrink many months after starting treatment.

After analyzing blood and tumor samples that had been collected over time from some participants, one finding of particular interest was that treatment with atezolizumab could "convert" tumors from those that initially lacked one of two proteins, PD-1 or PD-L1, needed for atezolizumab to work, to those that eventually produced high levels of either protein.

The findings have potentially important implications for how the drug is used, Dr. Chen and the team wrote.

Because of "the possibility of conversion" to a tumor that can respond to the drug, they continued, only giving it to those whose tumors initially have high PD-1 or PD-L1 levels "may exclude patients with ASPS who have the potential to [respond] to immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment."

Researchers are now looking at whether combining atezolizumab with other drugs might help boost its effectiveness, particularly among those that don’t respond to atezolizumab alone.

Dr. Chen and her colleagues have launched a trial comparing atezolizumab alone with atezolizumab in combination with selinexor (Xpovio), which works by blocking a key protein that tumor cells need to grow.

Meanwhile, for people like Faithanne, the approval provides a sense that she and others with ASPS may be able to spend less time recovering from surgeries and more time living their lives.

“Knowing that atezolizumab is approved gives you more hope that you will be okay,” she said.