Risk of Breast Cancer Death is Low After a Diagnosis of Ductal Carcinoma in Situ

, by NCI Staff

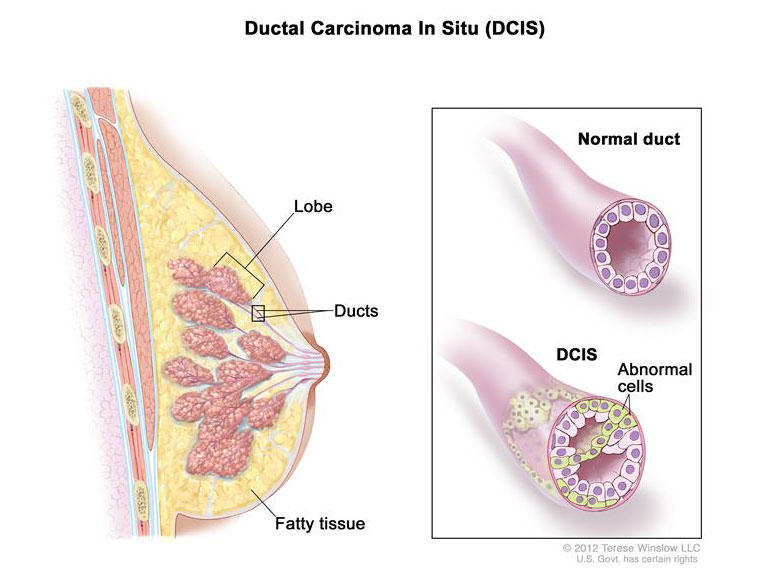

A new study suggests that women who are diagnosed with abnormal cells in the lining of a breast duct—a noninvasive condition called ductal carcinoma in situ, or DCIS—generally have a low risk of dying from breast cancer. In addition, treating these lesions may help prevent a recurrence in the breast but does not appear to decrease the already-low risk of dying from the disease, even after 20 years of follow-up.

The findings, from an observational study involving more than 100,000 women, were published August 20 in JAMA Oncology. Steven A. Narod, M.D., of the Women’s College Hospital, Toronto, and his colleagues used data from NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program to estimate the death rate from breast cancer among women diagnosed with DCIS.

DCIS refers to abnormal cells in the breast duct that form characteristic patterns detectable on mammography. In some cases, DCIS may become invasive cancer and spread to other tissues. At this time, because of concerns that a small proportion of the lesions could become invasive, nearly all women diagnosed with DCIS currently receive some form of treatment.

In the current study, most women received either a lumpectomy (with or without radiation therapy) or a single or double mastectomy. The overall death rate from breast cancer at 20 years after diagnosis was 3.3 percent, a rate similar to that of the general population. The death rates did not vary with the type of treatment used, the researchers noted.

“DCIS has extremely favorable outcomes irrespective of the type of therapy used,” said Barry Kramer, M.D., director of NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention, who was not involved in the study. He noted that treatments for DCIS are associated with potential harms. For instance, exposure to radiation therapy increases the risk of developing secondary cancers in the future, and mastectomy can cause serious health problems as well.

Some women with DCIS may be at an increased risk of dying from breast cancer, including those diagnosed at a younger age and African Americans, the study showed. Death rates were higher for women diagnosed before age 35 than for older women (7.8 percent versus 3.2 percent), and higher for African Americans than for Caucasians (7 percent versus 3 percent).

The mean age at diagnosis among women in the study was 54 years old, and less than 1.5 percent of the women with DCIS were under age 35.

The authors of an accompanying editorial said the study’s large numbers and long-term follow up provide a compelling case to reconsider how DCIS is treated.

“Given the low breast cancer mortality risk, we should stop telling women that DCIS is an emergency and that they should schedule definitive surgery within 2 weeks of diagnosis,” wrote Laura Esserman, M.D., and Christina Yau, Ph.D., of the University of California, San Francisco.

The finding of greatest clinical importance, the study authors noted, was the observation that preventing the development of invasive breast cancer in women diagnosed with DCIS did not reduce the chances of dying from breast cancer. For example, among women who had a lumpectomy, radiation therapy reduced the risk of a recurrence in the same breast compared with women not treated with radiation (2.5 percent versus 4.9 percent), but it did not reduce the risk of death from breast cancer 10 years later (0.8 percent versus 0.9 percent).

“The study showed that even though a lumpectomy can reduce the risk of a recurrence developing in the same breast, it does not change the risk of dying from the disease,” said Dr. Kramer. “This suggests that what you do locally to treat DCIS may not affect the risk of dying, which is the most important outcome.”

This observation, Dr. Kramer added, “gives us important insights into the biology of DCIS.”

In another finding, 517 women diagnosed with DCIS died of breast cancer without ever developing an invasive cancer in the same or other breast prior to death. Some cases of DCIS may have “an inherent potential” to spread to other parts of the body, the study authors wrote.

The finding, Drs. Esserman and Yau concluded, suggests that “our current approach of surgical removal and radiation therapy may not suffice for the rare cases that lead to breast cancer mortality and thus new approaches are needed.”

Dr. Kramer agreed that new approaches to managing DCIS are needed and said the new results help set the stage for this work. He cited a potential parallel with prostate cancer and the development of careful follow-up, rather than initial surgery, to manage screen-detected early stage cancers.

“Years ago, it was considered terribly ill advised not to treat prostate cancer,” he observed. But as the evidence grew that some prostate cancers detected through screening were slow-growing and better left alone, researchers began to test approaches such as watchful waiting and, later, active surveillance.

“We are starting to build the evidence to justify these kinds of studies in DCIS,” Dr. Kramer said. “We may not be there yet, but this kind of evidence helps us to justify studies to explore new approaches.”

Related Resources