Many Women with Dense Breasts May Not Need Additional Screening

, by NCI Staff

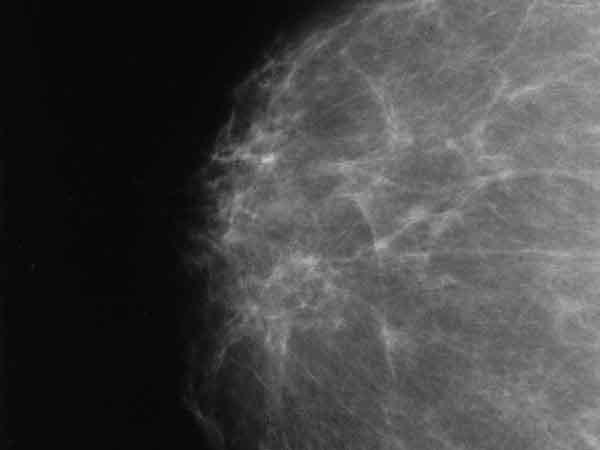

Women with dense breasts are at increased risk of breast cancer, and high breast density is a cause of false-negative results on a standard screening mammography. However, results from a new study suggest that breast density alone should not dictate whether women should receive additional screening for breast cancer after a normal result on a screening mammogram.

Rather, the NCI-supported study found, for women with dense breasts, a screening strategy that also takes into account other risk factors is the best predictor of developing a breast cancer after a negative mammogram and before their next mammogram, often referred to as an interval cancer.

“We found that for the vast majority of women undergoing mammography—including those with dense breasts but low 5-year breast cancer risk—the chance of developing breast cancer within 12 months of a normal mammogram was low,” the study’s lead investigator, Karla Kerlikowske, M.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, said.

The findings could have important implications for many women, the researchers believe, because 22 states currently have laws that require physicians to tell women if they have dense breasts and encourages these women to discuss with their providers undergoing additional imaging procedures—such as MRI, PET, or screening ultrasound—after a normal result on a screening mammogram.

Similar federal legislation is currently being considered by Congress. Although these additional imaging procedures can detect cancers missed by mammography, their use has also been found to increase false-positive results and to lead to additional procedures, including unnecessary biopsies.

Published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, the study used data from approximately 365,000 women ages 40 to 74 years in the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC), an NCI-funded program that includes seven breast cancer screening registries. Five-year breast cancer risk was determined using the BCSC risk model, which, in addition to breast density, includes age, race, family history of breast cancer, and breast biopsy history to estimate breast cancer risk over the next 5 years. Breast density was assessed using a standard measuring system known as BI-RADS.

Approximately 47 percent of women in the study had dense breasts, the study found. Among women with dense breasts, the risk of developing an interval cancer was greatest in those with extremely dense breasts (at least 75 percent of breast tissue is dense) and a 5-year risk of 1.67 percent or more and in those with heterogeneously dense breasts (more than half of the tissue in their breasts is dense) and a 5-year risk of 2.5 percent or more.

Only 24 percent of women with dense breasts were at the high risk of an interval cancer based on the BCSC risk model and thus were the best candidates for discussion of additional or alternative screening, Dr. Kerlikowske and her colleagues reported. And women at highest risk of interval cancer were also most likely to have advanced cancer when detected, which, they wrote, reinforced the idea that women at high risk of an interval cancer have the most potential to benefit from additional or alternative screening.

The BCSC risk calculator is designed as a tool to assist clinical decision-making. Primary care providers can calculate 5-year breast cancer risk using the risk calculator and use this information in their discussions about supplemental or alternative screening methods in women with dense breasts. The risk calculator can also be used to compare one woman’s risk relative to the average risk for a woman of the same age and ethnicity.

"This study is a good example of using information wisely to personalize risk estimation,” said Stephen Taplin, M.D., M.P.H., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences.

Based on the study’s results, Dr. Kerlikowske said, “It just doesn’t make sense for all women with dense breasts to get additional screening.”