Large Study Verifies Cancer Risk for Women Carrying BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutations

, by NCI Staff

An international team of researchers has published results from the first large prospective study of breast and ovarian cancer risk in women who carry inherited BRCA mutations.

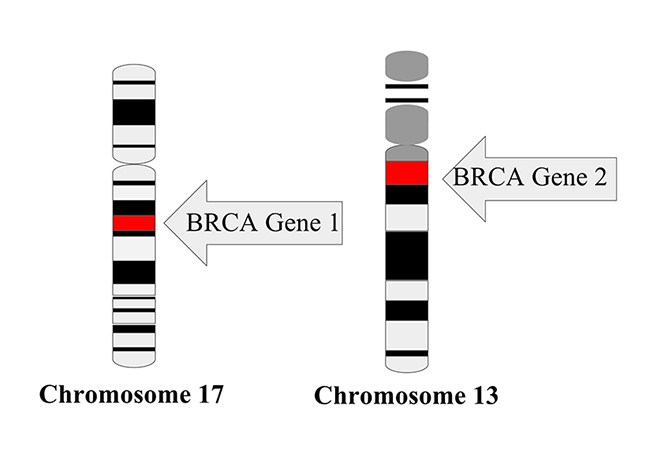

The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes code for proteins that are critical for cells to repair damaged DNA. Specific inherited mutations in these genes increase the risk of several cancer types, particularly breast and ovarian cancer. The study affirmed earlier estimates of a substantial increased lifetime risk of these cancers in carriers of inherited mutations. But it also showed that the magnitude of risk is influenced as well by the location of the mutations within the BRCA genes and the extent of the family history of breast cancer.

“This study has confirmed estimates of the risk of developing cancer for women who are mutation carriers—that confirmation is reassuring for both women and the health care team who make important care decisions,” commented Montserrat García-Closas, M.D., Dr.P.H., deputy director of NCI's Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, who was not involved in the research.

The study was published June 20 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Looking Forward at Risk

Women who know they have inherited a harmful BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation can take steps to reduce their risk of breast and ovarian cancer. But any preventive measures—including intensive early surveillance, use of chemoprevention, and prophylactic surgery—come with their own risks. Estimates of cancer risk and of the risk reduction provided by preventive measures can help women make decisions about which of these options to pursue.

Until now, health care professionals who counsel BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers about their risk of cancer have mostly had to rely on data from large retrospective studies—studies that enrolled women after they’d already been diagnosed with cancer. Most of these retrospective studies include women with cancer in their family, rather than women recruited from the general population. Although many of the retrospective, family-based studies used for such risk estimates have been of high quality, they carry the risk of bias because of their backward-looking nature and the way participants in family-based studies are recruited, explained Dr. García-Closas.

For the current study, the investigators, led by Antonis C. Antoniou, Ph.D., of the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, used data collected from BRCA mutation carriers recruited by three different research consortia: the International BRCA1/2 Carrier Cohort Study, the Breast Cancer Family Registry, and the Kathleen Cuningham Foundation Consortium for Research Into Familial Breast Cancer.

Data from 6,036 women carrying a BRCA1 mutation and 3,820 carrying a BRCA2 mutation from the three registries were analyzed to determine their cumulative risks, to age 80, of breast cancer and of ovarian cancer. To be included in the analyses of breast cancer risk, women could not have been previously diagnosed with any cancer or have undergone prophylactic mastectomy.

For inclusion in ovarian cancer analyses, women could not have previously been diagnosed with ovarian cancer or have undergone risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes).

The researchers also looked at the risks of contralateral breast cancer risk in women who had been first diagnosed with breast cancer at least one year earlier.

All registries followed participants using questionnaires, and with records from cancer, pathology, and death registries when available. Medical records were used to validate self-reported cancer diagnoses and risk-reducing surgeries. Participants were followed for a median of 5 years.

Necessary Confirmation

As in the retrospective studies, the risk of cancer was high in both those with specific BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.

Of the 3,886 women eligible for the breast cancer risk analysis, 426 developed breast cancer during the study period. The peak incidence of breast cancer was seen in women 41–50 years old for BRCA1 mutation carriers and those 51–60 years old for BRCA2 mutation carriers. The cumulative risk estimates for developing breast cancer by age 80 were 72% for BRCA1 carriers and 69% for BRCA2 carriers.

Among the 5,066 women enrolled in the ovarian cancer risk analysis, 109 were diagnosed with ovarian cancer during follow-up. For mutations in both BRCA genes, the risk of ovarian cancer increased with increasing age, until women reached ages 61–70. The cumulative risk estimates for developing ovarian cancer by age 80 were 44% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 17% for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

For the 2,213 women eligible for the contralateral breast cancer risk analysis, the cumulative risk of a contralateral breast cancer 20 years after a first breast cancer was 40% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 26% for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Looking Beyond BRCA Mutations

Other factors also influenced cancer risk in the women in the study, the researchers found. For carriers of both BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, the risk of breast cancer increased with the number of first-degree relatives (such as a mother or sister) or second-degree relatives (such as an aunt or cousin) who had been diagnosed with breast cancer.

Family history did not significantly influence the risk of ovarian cancer. However, the number of ovarian cancers in women with a family history of the disease was small, which limits the statistical strength of the finding

The position of the actual mutation in either the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene also played a role in breast cancer risk, with mutations in some locations conferring more risk than mutations in other locations. Together, these results suggest that “individualized counseling should incorporate both family history profiles and mutation location,” the paper’s authors wrote.

Many software tools used in genetic counseling, such as BRCAPro or BOADICEA, already incorporate family history information, explained Dr. García-Closas.

“While the instinct is to view confirmatory results with less enthusiasm, these types of studies are necessary, because it’s not always the case that when you address some of potential biases or limitations [in retrospective studies] you still get similar results,” she added.

In this case of cancer risk for BRCA mutation carriers, Dr. García-Closas concluded, “it’s very good news that the estimates that we’ve been working with are accurate.”