Lung Cancer Trial of Osimertinib Draws Praise—and Some Criticism

, by Carmen Phillips

Highly anticipated results from a large study of people with early-stage lung cancer are generating praise, and some controversy, among oncologists who specialize in treating people with this cancer.

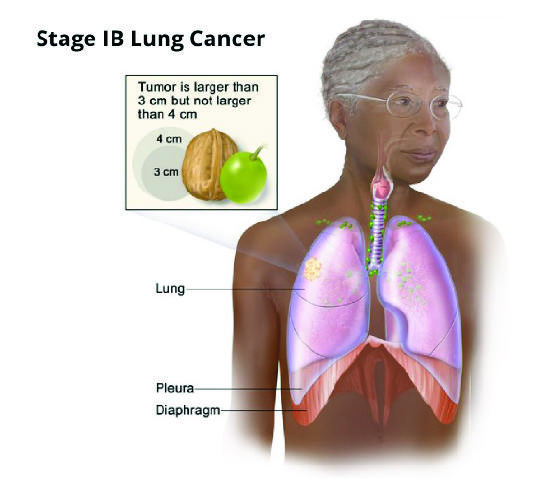

The clinical trial, called ADAURA, tested giving the drug osimertinib (Tagrisso) after surgery in people with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). All trial participants’ tumors had specific mutations in a gene called EGFR. Osimertinib, which is taken daily as a pill, specifically targets and kills lung cancer cells with these genetic mutations.

In the nearly 700-patient study, people who were randomly assigned to receive osimertinib after surgery to remove their tumor(s)—known as adjuvant therapy—lived substantially longer overall than people assigned to receive a placebo after surgery. At 5 years after starting adjuvant treatment, 88% of people treated with osimertinib were still alive, compared with 78% of those treated with a placebo.

The findings “herald a new era of targeted therapy in early-stage [lung cancer],” said the trial’s lead investigator, Roy Herbst, M.D., of the Yale Cancer Center, who presented the data on June 4 at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO). The results were published the same day in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many other lung cancer experts agreed. In a commentary on the ADAURA results delivered at the ASCO meeting, Ben Solomon, M.B.B.S., Ph.D., of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Center in Australia, called the findings “groundbreaking.”

But other oncologists who specialize in treating lung cancer or conducting cancer clinical trials were less enthusiastic. Their primary criticism focused on the treatments received by participants in the placebo group, or control arm, whose cancer came back: Only about 40% received osimertinib.

In the United States and much of Europe, osimertinib is the standard therapy in people with early-stage lung cancer that relapses.

So the extent to which adjuvant osimertinib increased how long participants in ADAURA lived is unclear “because so many patients [in the control arm] didn’t get the standard care,” said Bishal Gyawali, M.D., Ph.D., an oncologist at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada.

“This is a very good drug,” Dr. Gyawali continued. But in people with early-stage lung cancer whose tumors have EGFR mutations, he said, it’s still unclear from the trial’s results if it’s “appropriate for everyone to receive [osimertinib] immediately after surgery versus receiving the same drug at the time of relapse.”

EGFR inhibitors: From advanced- to early-stage lung cancer

Drugs that target lung cancers with EGFR mutations have been among the most successful of the targeted cancer therapy era that began more than 2 decades ago.

Osimertinib is often referred to as a third-generation EGFR inhibitor, because it was designed to address some of the shortcomings of earlier EGFR inhibitors. Key among the properties of osimertinib is an improved ability to get into the brain and, thus, shrink tumors that have spread there from the lungs—a common occurrence in NSCLC.

Osimertinib is already the standard therapy for people with metastatic NSCLC whose tumors have EGFR mutations and in those initially diagnosed with early-stage disease but whose cancer comes back, explained Charu Aggarwal, M.D., who specializes in treating lung cancer at the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Cancer Center.

And even with the dramatic improvements in the treatment of metastatic lung cancer, once the cancer has spread, it’s often fatal. Less than half of people initially diagnosed with stage IIIA NSCLC, in fact, will still be alive 5 years later.

So the ADAURA trial—which was funded by AstraZeneca, osimertinib’s manufacturer—was launched in late 2014 to see if adding osimertinib as an adjuvant therapy for early-stage NSCLC with EGFR mutations might improve outcomes.

Specifically, the ADAURA research team wanted to know if it could prevent, or at least substantially delay, the disease from returning, and increase how long people live overall.

Approval based on increased progression-free survival

The initial results from ADAURA, published in October 2020, offered signs of possible survival improvements with adjuvant osimertinib. This treatment, they showed, dramatically improved how long people lived without any evidence of their cancer returning.

Not long after, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved osimertinib as an adjuvant therapy for people with early-stage NSCLC (stages IA to IIIB) with certain EGFR mutations. That led at least some US oncologists to start routinely using osimertinib as an adjuvant therapy for these patients, Dr. Aggarwal said—at least in hospitals and cancer centers where mutation testing in tumors is a standard practice.

Although the reasons vary, she continued, failure to routinely perform testing for EGFR mutations “has been an issue.”

But some oncologists argued that, before any wholesale changes in patient care, it was important to see if the drug also helped people live longer. This is particularly important, they argued, because osimertinib can have persistent side effects and can cost nearly half a million dollars a year.

Both are important considerations, because in ADAURA, people assigned to receive osimertinib were to take it for 3 years.

Improved overall survival with longer follow-up

In total, 682 people participated in the study. Participants were allowed to receive chemotherapy after surgery (but before starting adjuvant osimertinib or placebo), and about 60% did. Treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy was most frequent in people with stage II and IIIA disease (71% and 80%, respectively).

The large improvement in survival, Dr. Solomon noted, was seen regardless of the extent of participants’ cancer. When the analysis was limited to people with stage II to IIIA tumors, for example, the 5-year survival rate was 85% in the osimertinib group and 73% in the placebo group.

Osimertinib’s side effects in the trial were consistent with what is typically seen with this drug, with diarrhea and rash among the most common. In the osimertinib group, 13% of people stopped taking the drug entirely because of side effects, and another 27% stopped taking it for periods but then resumed treatment.

Dr. Solomon cautioned that 3 years is a long time to be on a therapy, and that side effects, even if they seem minor, shouldn’t be discounted.

“It’s important for clinicians not to underestimate the impact of continued [low-grade] toxicities on patients,” he said. Such side effects can include diarrhea, dry skin and rash, frequent coughing, and fingernail and toenail infections, among others.

But was the ADAURA placebo group an adequate comparison?

With the trial’s details published, some oncologists began to point out what they viewed as problems with the treatments given to those in the control arm—specifically, the limited number who received osimertinib once their cancer relapsed.

On Twitter, H. Jack West, M.D., a lung cancer expert at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Los Angeles, argued that “ADAURA is unfortunately a trial of 100% access to [osimertinib] vs <50% access to [osimertinib].” Instead, he wrote, the control arm should have been osimertinib “for all [patients] at relapse, as needed.”

At the ASCO meeting, Dr. Herbst noted that in the first few years of the trial, osimertinib was not yet approved for treating metastatic NSCLC in the United States and some other countries. So early on, at least, the drug wasn’t available to patients in the control arm whose cancer returned, he said.

Later, after the initial trial results showed the improvement in disease-free survival, control arm participants could be offered the drug if their cancer relapsed after surgery.

Even with that change, however, many patients in the control arm whose cancer relapsed ended up getting earlier-generation EGFR inhibitors. And 15% received no additional treatment at all.

Importance of testing for EGFR mutations

Despite the concerns expressed about the control arm, there seems to be little disagreement that oncologists should discuss adjuvant osimertinib therapy with their patients with early-stage NSCLC that has EGFR mutations.

Dr. West wrote that he believed the overall survival improvement with adjuvant osimertinib “would hold up even if issues around [ADAURA’s] conduct were not present.”

Dr. Gyawali agreed with Dr. West, while also highlighting a larger concern. “That does not mean we should not criticize the trial’s flaws,” he said. Voicing legitimate criticisms is important, he continued, so similar problems “don’t happen in future trials.”

For her part, Dr. Aggarwal said there was now little doubt about what should be happening in everyday clinical practice. “This confirms our practice to test for EGFR mutations and recommend adjuvant targeted therapy with osimertinib” for those whose tumors have the genetic changes, she said.

Osimertinib isn’t an option, however, if patients aren’t tested for EGFR mutations. And as another study presented at the ASCO meeting showed, although testing rates appear to be increasing, they are far from 100%.

Ensuring that all patients with early-stage NSCLC are tested for EGFR mutations is essential, Dr. Herbst said. “The only way we’re going to find these mutations is if we look for them.”

Other studies are ongoing to help better guide the treatment of early-stage lung cancer and how best to use osimertinib, he explained.

One clinical trial, called NeoADAURA, for example, is looking at the impact on patient outcomes of using osimertinib before surgery. And some researchers have already shown the potential of analyzing bits of tumor DNA floating in the blood to determine the need for adjuvant therapy or to monitor if the cancer has come back.

“We need to be able to personalize therapy,” Dr. Aggarwal said. These and other studies are pushing in that direction, she added. “We don’t have the right tools yet. But I think in the near future we’ll get there.”