How a Simple Tool Is Saving Lives of Children with Cancer in Latin America

, by Nadia Jaber

Advances in the treatment of childhood cancer have led to remarkable progress. In high-income countries like the United States, more than 80% of children with cancer survive their disease.

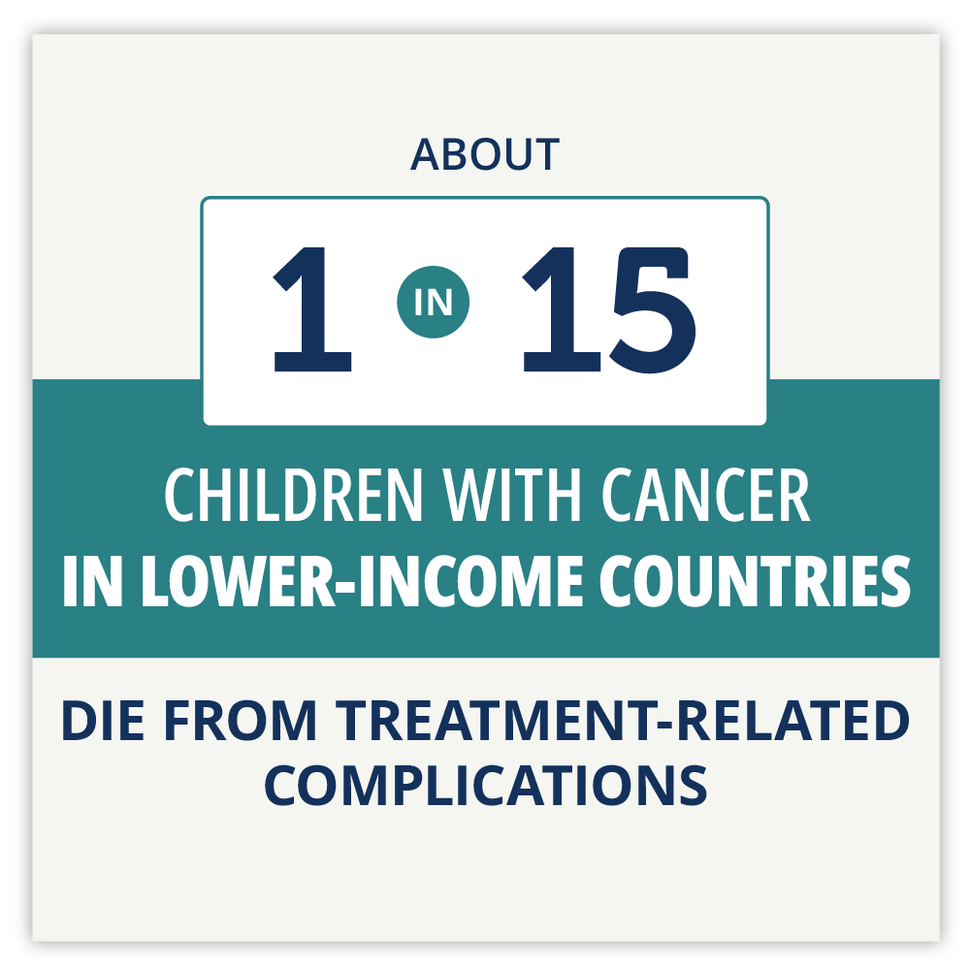

In stark contrast, however, only 20% of children with cancer in lower-income countries survive their disease. Close to one-third of those deaths are caused not by the cancer, but by complications from the treatment such as severe infections, organ failure, and hemorrhage.

But an international team led by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital is hoping to change that statistic in Latin America with a simple tool called a pediatric early warning system (PEWS). The warning system identifies children who are suffering from severe treatment-related complications and guides the clinical team through the next steps for care.

Early warning systems “are pretty ubiquitously used in hospitals that care for children in high-resource settings. But, prior to our work, [PEWS] were very underused in resource-limited settings,” said Asya Agulnik, M.D., M.P.H., director of the global critical care program at St. Jude.

Through a program called Proyecto Escala de Valoración de Alerta Temprana (EVAT), Dr. Agulnik and the team have supported implementation of an early warning system in nearly 100 hospitals across Latin America and Spain.

The results have been consistent and extremely positive: the early warning system has helped save the lives of many children hospitalized with cancer.

“Childrens’ health conditions were deteriorating, and we didn’t know until they were in critical condition,” said one nurse at a hospital in Ecuador. “But with [PEWS] everything changed … [now] we don’t wait until it’s too late” to escalate their care.

But will these hospitals continue to use the early warning system long-term?

That’s a critical question because only long-term use of tools like PEWS “results in truly beneficial progress,” said Marie Ricciardone, Ph.D., a program director in NCI’s Center for Global Health.

Through a 7-year project funded by NCI, a team of researchers at St. Jude and Washington University aim to learn what factors help keep the early warning system in use at low-resource hospitals in Latin America. And once they understand what makes PEWS stick, the funding will also help them develop strategies to keep the tool in use at hospitals that are struggling to maintain it.

There’s been very little research on what promotes sustained use of effective programs and tools, noted Virginia McKay, Ph.D., of Washington University in St. Louis, the project’s co-leader.

And even less is known about sustaining health programs and tools in low-resource settings, Dr. McKay explained. But sustainability is especially important in that context because the initial investment for implementing a new program or tool is typically expensive, she argued.

“In low-resource settings, you may only get one opportunity every once in a while to do something new because the resources are so constrained. So, it’s really important that [the new program or tool] is sustainable,” Dr. McKay explained.

“If [the new project is] successful, it has the potential to really remarkably change the outcomes for pediatric cancer in Latin America,” emphasized Dr. Ricciardone, who oversees the study’s funding.

Deaths related to cancer treatment

Childhood cancer is an unforgiving disease that, in many cases, requires intense and harsh treatment. Doctors strive to give each child enough treatment to knock the cancer out for good, but not so much that the child’s body is irreparably harmed.

It’s a delicate balancing act that isn’t always achieved. Sometimes, complications from the treatment can tragically take a child’s life.

While such deaths are a rare occurrence in high-income countries, they are a significant challenge in low- and middle-income countries, where there are few medical facilities and specialized resources to meet the unique needs of children with cancer.

Many hospitals in lower-income countries are understaffed and have high staff turnover rates. Some countries, like El Salvador, have only a single hospital equipped to deliver cancer care to children.

Even with those limitations, there’s recently been great improvements in access to effective cancer treatments in low- and middle-income countries, Dr. Agulnik said.

“But there hasn’t been a concordant focus on supportive care,” which includes intensive care facilities, tools for pain management, and measures for preventing infections, she pointed out.

“If you don’t have all of those things—not only the equipment, but also the processes and the protocols and the practices of how to use them—you [will] have more complications from treatment,” she said.

A recent study found that there hasn’t been any change in cancer treatment–related deaths in low-income and lower middle-income countries over the past 30 years.

Bringing research advances to the real world

Dr. Agulnik—a specialist in pediatric critical care—cares for children in critical condition, often in the pediatric intensive care unit (ICU). Among all her patients, children with cancer are typically the sickest and require the most medical attention, she said.

As a young doctor, she often thought about children with cancer in hospitals that have far fewer resources than St. Jude. She wanted to do better for those patients.

When it comes to preventing cancer treatment–related deaths, the problem isn’t a lack of affordable, effective strategies, Dr. Agulnik explained. Early warning systems are a low-cost, proven way to avoid these deaths.

Rather, the problem lies in taking proven tools like early warning systems and working them into routine medical practice, she said. The branch of research focused on getting effective treatments and tools into routine health care is called implementation science.

It typically takes years for a new research advance to reach patients, noted Dr. McKay. As an implementation scientist, Dr. McKay helps researchers get their innovations out of the lab and into routine medical practice.

“We start with scientific information … then we actually have to get it integrated and then we have to maintain it,” Dr. McKay said. “There are problems at absolutely every point in this [pipeline] that leads to innovations not being used.”

Many new treatments or tools are proven effective in clinical studies “and then nothing else happens. Bringing it to the real world is really where the challenge is,” Dr. Ricciardone agreed.

That’s often because implementation is an afterthought of the research process, Dr. McKay said. And even less thought is given to the long-term use of new treatments or tools, she added.

But researchers at Washington University and St. Jude have been considering these aspects from the beginning of Proyecto EVAT, as well as for many other cancer research advances.

A pediatric early warning system

Pediatric early warning systems consist of two relatively simple steps.

First, a nurse does a physical exam and takes the child’s vital signs and uses a score chart to calculate a score for the child’s condition. The nurse then uses an algorithm to determine what level of care the child needs. The scores are also tied to a color system that makes it easy to communicate to other staff members.

For instance, if the score is low (green), the child continues to receive routine care. But if the score is high (yellow or red), the child gets an intensive care consultation.

For Proyecto EVAT, the team took a pediatric early warning system that was originally developed by Boston Children's Hospital and translated it into Spanish. They then adapted the tool to fit the procedures of each hospital it was implemented in.

With PEWS, “we do a thorough job to see every detail of the patient in [their] neurological, cardiac, respiratory status,” said Patty Mejía, a nurse at a hospital in El Salvador. “We even take the parent’s worry and the nurse’s concern [into account], which we didn’t do before.”

PEWS “is a communication tool that, in the end, allows us as nurses to communicate to the doctor how the patient is,” said Nidia Romero, a nurse at a hospital in Guatemala.

Before PEWS was implemented, a nurse could tell a doctor that a child’s condition didn’t look good.

But now, the nurse can say that a patient’s PEWS is red, and the doctor will immediately know what that means, explained Silvana Espinoza, a nurse supervisor at a hospital in México.

Bringing PEWS to Latin America

In Guatemala, a children’s oncology hospital called Unidad Nacional de Oncología Pediátrica provides care to more than half of all children with cancer in the country. Prior to 2013, the hospital didn’t have a protocol for managing children with cancer whose condition was worsening.

But the staff were very motivated to change that, Dr. Agulnik said. In 2013, she and others joined forces with the hospital to implement PEWS. After the tool was implemented, there were fewer unplanned transfers of children with cancer to the pediatric ICU.

PEWS “is a very useful tool that has facilitated the detection of the deterioration of our patients,” said Gladys Aceituno, chief nurse at the children’s oncology hospital in Guatemala.

With the success of PEWS in Guatemala, Dr. Agulnik and her colleagues began expanding their efforts to other countries. They have since supported PEWS implementation in nearly 100 hospitals in 20 countries. Altogether, more than 16,000 nurses and physicians have been trained to use the tool.

The effort has been a resounding success. The early warning system has helped hospital staff identify critical illness earlier and provide appropriate care for those patients in a timely way.

As a result, deaths among young cancer patients in critical condition dropped from 39% to 29%. The researchers estimated that PEWS use throughout the study period at all centers could have averted about 80 deaths.

What’s more, hospitals that previously had the highest rates of treatment-related deaths saw the greatest reduction of deaths among patients in critical condition after implementing PEWS.

“This work is an example of how implementation science can—and, we think, should—be used to reduce global disparities in childhood cancer outcomes,” Dr. Agulnik said.

PEWS has also led to other benefits for the hospitals and the patients and families they serve. It has improved communication between families and medical teams, boosted the confidence of medical providers, and resulted in cost savings for many hospitals.

For many staff members, talking about the impact of Proyecto EVAT is emotional. In several hospitals, the work is dedicated to the memory of “a patient who deteriorated when we didn’t have PEWS, and we didn’t do what we had to do,” said Angélica Martínez, a doctor and PEWS team leader at a hospital in México.

Sustaining PEWS long-term

Since implementing PEWS, some hospitals have used it consistently while others have struggled to maintain it, and still others have abandoned it altogether, Dr. McKay said. Through the new NCI-funded project, called INSPIRE, the researchers are starting to uncover why.

In a recent study, they interviewed more than 70 doctors, nurses, and administrators who helped implement PEWS at their respective hospitals. Through these interviews, the researchers learned that things like having supportive hospital leadership helped sustain PEWS. But ongoing challenges included the need for continuous training due to high staff turnover.

The COVID-19 pandemic also required some hospitals to direct nearly all their efforts on pandemic-related measures, forcing some to move PEWS to the sidelines.

The INSPIRE team is now taking a more quantitative and empirical approach to identifying factors that sustain PEWS in hospitals in Latin America. The project is also an opportunity to develop strategies to improve hospitals’ ability to sustain PEWS.

“To my knowledge, [the INSPIRE project] is the first of its kind,” Dr. McKay said, moving sustainability research from theory to actual assessment.

Dr. Ricciardone agreed, saying there are no other NCI-funded projects like INSPIRE. “This is unique,” she said.

Implementation scientists have “done a lot of work to understand how to make people aware of evidence-based interventions, how to entice them to adopt them, [and] how to get them up and running,” Dr. McKay said. But there’s been much less research on what promotes and prevents sustained use of effective programs and tools, she added.

Dr. McKay and her colleagues have long called attention to the large gaps in knowledge about sustainability of health programs and tools. They have also worked to define what sustainability is and ways to measure whether a program or tool is sustainable.

Given the general lack of information about sustainability, lessons learned about PEWS could potentially contribute to the success of other cancer programs and interventions, Dr. Ricciardone noted.

“What's exciting for me is that I do believe that [this work] will have real-world impact for years down the line,” Dr. McKay said. “And for me, that is wildly rewarding.”