The Playing Field for Cancer Checkpoint Inhibitors Is Expanding

, by NCI Staff

The list of cancers that may be susceptible to immunotherapy drugs known as checkpoint inhibitors is quickly expanding, according to findings from three early-stage clinical trials presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting.

In addition, results of one of the trials point to a genetic alteration that may further define which patients are most likely to benefit from one type of checkpoint inhibitor.

All three early-stage trials tested therapies that target a protein on T cells called PD-1—a member of a family of immune checkpoint proteins, so called because of their role in dialing down immune activity.

Two of the trials involved pembrolizumab (Keytruda®), which is already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat patients with advanced lung cancer.

In one of the pembrolizumab trials, the drug substantially reduced the size of tumors in patients with colorectal, uterine, stomach, and several other types of cancer. All of the patients in the trial had advanced cancer that had progressed after several lines of treatment.

In patients with colorectal cancer, which represented the largest patient group in the trial, those whose tumors had a specific genetic alteration known as DNA mismatch repair (MMR) deficiency (MMR-deficient tumors) were far more likely to respond to pembrolizumab than those whose tumors had a largely intact MMR system, reported the trial’s lead investigator, Dung Le, M.D., of the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center.

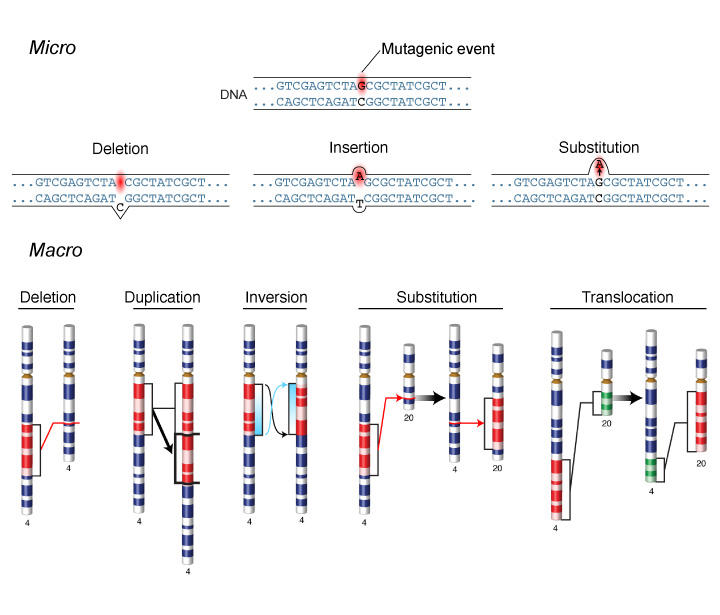

MMR is a mechanism that repairs mistakes that are made during DNA replication, and cells with defective MMR tend to accumulate more genetic mutations.

Among the patients with colorectal cancer, 8 of the 13 whose tumors were MMR-deficient had substantial tumor regressions when treated with pembrolizumab (median follow-up 8.3 months), compared with none of the 25 patients whose tumors were MMR-proficient (median follow up 4.9 months). In a third group of patients with different cancers, all of which were MMR-deficient, 6 of 10 responded to pembrolizumab, including a patient with uterine cancer who had a complete response (median follow-up 7.1 months).

Of the patients who have had responses, only one has since experienced tumor progression.

Tumors in patients with MMR-deficient disease had an average of approximately 1,700 mutations, Dr. Le noted, compared with only 70 in patients with MMR-proficient tumors.

The effect of all of those mutations in a tumor is profound, said Lynn Schuchter, M.D., of the University of Pennsylvania Abramson Cancer Center, who moderated a press briefing on the studies. “It’s like putting a red flag on the cancer cell that says to the immune system, ‘Here I am,'" she said.

James Gulley, M.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research, whose research focuses on immunotherapy, agreed. The data on MMR-deficient tumors, he said, strengthens the concept that tumors with more mutations express more so-called neoantigens, which allow the tumor to be more easily recognized by the immune system.

Although evidence is emerging that immune checkpoint modulation can work if the immune system can recognize even a single specific neoantigen, Dr. Gulley noted, “perhaps the more shots on goal the better.”

Merck, which manufactures pembrolizumab, expects to launch a phase II clinical trial later this year of pembrolizumab in patients with MMR-deficient advanced colorectal cancer.

The other pembrolizumab trial enrolled more than 120 patients with advanced head and neck cancer. Approximately 25 percent of patients had tumor responses to the drug. An additional 25 percent of patients had stable disease, meaning that their disease did not progress during follow up.

To see these types of results “is remarkable in this disease,” said the trial’s lead investigator, Tanguy Seiwert, M.D., of the University of Chicago Cancer Center. Overall, with a median follow-up of 5.7 months, the responses have been long-lasting, with 25 of the 29 patients who have responded still showing no signs of progression, he said. Head and neck cancers are usually grouped as either human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive or HPV-negative, Dr. Seiwert noted, and responses were seen in both types.

In the third trial, nearly 20 percent of patients with advanced liver cancer had tumor responses after treatment with a different PD-1 inhibitor, nivolumab (Opdivo®), reported Anthony B. El-Khoueiry, M.D., of the University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center. Nivolumab is approved by the FDA for the treatment of advanced melanoma and lung cancer.

Treatment advances in liver cancer have been extremely rare, Dr. El-Khoueiry said. The FDA has only approved one systemic treatment for liver cancer, sorafenib (Nexavar®), and the response rate is only 2 to 3 percent, he added.

Data from 42 patients in the trial were reported at the ASCO meeting. Of the eight patients who experienced substantial tumor shrinkage, two had complete responses that have lasted for more than a year, and most of the remaining partial responses are still ongoing.

The idea that some cancer types aren’t amenable to immunotherapy “is dead,” Dr. Gulley said. “But there is a need for further genomic profiling of tumors that establishes associations with clinical responses to immune checkpoint modulation.” It’s becoming apparent, he continued, that in many cancers there “may be select groups of patients who will have strong responses.”