Targeted Therapy Larotrectinib Shows Promise in Early Trials, Regardless of Cancer Type

, by NCI Staff

On November 26, 2018, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted an accelerated approval to larotrectinib (Vitrakvi) for the treatment of some adults and children with cancer whose tumors have a gene fusion involving one of the NTRK genes.

The new approval—the first for a TRK-targeted drug—covers both the pill and liquid forms of larotrectinib. The liquid form was specifically developed for use in children.

The approval by FDA was based on findings from a series of small clinical trials in patients with an array of cancer types, including many rare cancers. In the trials, larotrectinib was shown to be highly effective at either shrinking tumors or keeping them from progressing, often for long periods (see story below).

Further details on the approval are available in FDA’s approval summary.

Initial results from a series of three small clinical trials of a targeted cancer therapy called larotrectinib suggest that it may be effective in patients—children and adults—with a wide variety of cancer types.

The drug disrupts the activity of TRK proteins caused by an alteration, known as a fusion, in a family of genes known as NTRK. In all three trials, larotrectinib treatment shrank tumors in many patients whose tumor cells overexpressed TRK fusion proteins.

And larotrectinib appeared to largely be safe, with little evidence thus far from the trials that it causes any serious side effects.

The trials were supported by Loxo Oncology (which developed larotrectinib), NCI and other NIH institutes, and several nonprofit groups.

Overall, among patients with the NTRK alterations who were treated in the trials, 75% experienced reductions in the size of their tumors (partial response) or their tumors stopped growing, the trials investigators reported February 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

In seven patients, cancer was no longer detectable following treatment (complete response). And in a few patients, including several children with a rare form of sarcoma, tumors shrank enough that the patients were able to undergo surgery that could be potentially curative.

Although targeted therapies are now broadly used to treat cancer, most targeted agents are typically only effective in patients with one or two cancer types, said Alexander Drilon, M.D., a principal investigator of this trial at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. With larotrectinib, that cancer type specificity isn’t seen.

“Where the cancer originates doesn’t seem to matter,” Dr. Drilon said. As long as the patient’s tumor has the appropriate molecular alteration, he continued, “there’s a good chance it will respond.”

Based on these early results, Loxo has already begun the process of applying for Food and Drug Administration approval of larotrectinib.

A Rare, But Shared, Alteration

There are three different NTRK genes, which code for TRK proteins (pronounced “track” or “trek”). Although they are active in nervous system tissues in adults—having roles in areas like pain perception, memory, and appetite—TRK proteins’ most critical role is promoting brain and nervous system development in embryos.

But NTRK genes also are prone to rearrangements—that is, swapping segments with other genes—creating fusion genes. These NTRK fusion genes, in turn, can produce TRK fusion proteins that can fuel the development and growth of tumor cells. In fact, tumor cells can become almost solely reliant on, or “addicted” to, the growth signals produced by TRK fusion proteins.

From “OncD” to TRK

As is the case with many new cancer treatments, NCI played a part in the science that led to the FDA’s approval of larotrectinib.

In fact, in 1982, it was researchers at NCI, led by Mariano Barbacid, Ph.D., who reported that they had discovered a gene—which they initially called OncD—in a sample of a human colon cancer that could “transform” normal cells into cancer cells. This was among the first discoveries of a cancer-causing gene or, as they’re commonly called, oncogenes.

In 1986, Dr. Barbacid (now at the National Center for Oncological Research in Spain) and other NCI colleagues reported that they had more fully mapped OncD, discovering that it was, in fact, a fusion gene. Because the fusion gene had components of genes involved in producing the protein tropomyosin and a previously unknown type of protein known as a kinase, they changed the name of their discovery from OncD to TRK.

Only about 1% of solid cancers have NTRK fusions, according to current estimates. However, unlike some other genetic alterations that are targeted by cancer therapies, NTRK fusions are found in many different types of tumors, Dr. Drilon explained.

The trials included in the NEJM report, for example, included patients with 17 unique cancer types with NTRK fusions (including 5 types of sarcoma), and treatment responses were seen in patients with 13 of those 17 types.

But NTRK fusions seem to be most common in several rare cancer types, Dr. Drilon noted, including infantile fibrosarcoma and several other types of sarcoma, secretory breast carcinoma, and other cancers like papillary thyroid cancer to a lesser extent.

As more patients’ tumors are tested, NTRK fusions will likely be found in an even larger number of cancer types, said Nita Seibel, M.D., head of Pediatric Solid Tumor Therapeutics in NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program.

Dr. Seibel pointed to the cases of other cancer-causing fusion genes like BCR-ABL and those involving the ALK gene, both of which were initially identified in a single cancer (chronic myelogenous leukemia and non-small cell lung cancer, respectively) and were successfully treated with a new targeted therapy. Both alterations were later found in one or two other cancer types and could be treated effectively with the targeted drug.

“That is why it will be important to screen many different types of tumors in large precision medicine studies such as the NCI-COG Pediatric MATCH trial,” she continued. (See “Testing Larotrectinib in NCI-MATCH and Pediatric MATCH.”)

So Far, Long-Lasting Responses

Most of the patients with NTRK fusions who responded to larotrectinib in the three trials had partial responses. In addition to the seven complete responses, seven other trial participants had stable disease, which is defined as no substantial reduction in tumor size, but no progression either.

Several children in the initial patient group had infantile fibrosarcoma, which, when it reaches more advanced stages, often requires limb amputations to treat the cancer. In two of the children, larotrectinib shrank their tumors enough that they were able to undergo surgery to remove the remaining tumor without the need for amputation; at the time of patient follow-up, there was no evidence that either child’s cancer had returned.

Overall, at a median follow-up of approximately 9 months, 86% of the patients in the trial who responded to larotrectinib continued to receive the daily treatment or “had undergone surgery that was intended to be curative,” the research team reported. In fact, the very first patient with an NTRK fusion to be treated with the drug was still taking it more than 2 years later.

Thus far, larotrectinib appears to be safe. No patients in the initial treatment groups had to stop treatment because of side effects, and only a handful had to have the dose of the drug reduced.

Among the more common side effects were anemia and elevated levels of enzymes that can indicate potential liver damage. None of the side effects seen in the initial patient group were clinically significant, the research team reported.

Dr. Drilon attributes larotrectinib’s apparent safety to its design.

“It’s a really clean drug. It only targets TRK [fusion proteins], so it has few of the off-target side effects” seen with some other targeted therapies, he said. “That’s really important because it means patients can potentially take [larotrectinib] for a prolonged period of time.”

Despite these initially promising results, some researchers voiced caution, noting the importance of seeing how the drug performs in a larger group of patients.

These early trials, said Margaret von Mehren, M.D., who heads the Division of Sarcoma Medical Oncology at Fox Chase Cancer Center, “may include a somewhat selected group of patients who…may have biologically less aggressive disease.”

But even with the limited patient experience with larotrectinib, Dr. von Mehren continued, the results with the drug to date “reinforce the concept of targeted therapy and the benefits you can see when you target a tumor that is driven by a defined biologic process.”

A “Practice-Changing” Opportunity in Some Childhood Cancers?

One of the three trials in the NEJM report, called SCOUT, enrolled only children (Loxo developed a liquid formulation of larotrectinib for use in children and older patients who can’t take pills). Updated results from 17 patients in this trial were presented in December 2017 at the AACR Special Conference on Pediatric Cancer Research.

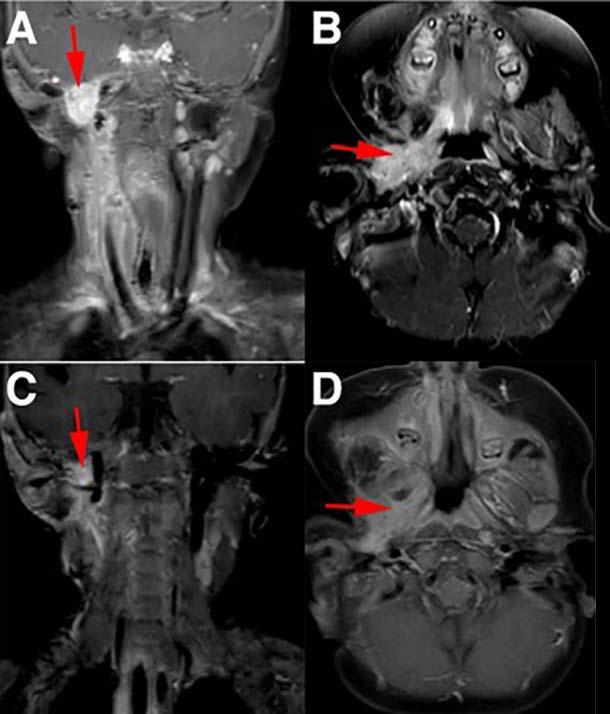

All but one of those 17 patients responded to larotrectinib, including several who had complete responses. One of the complete responses occurred in a child with glioblastoma, a highly fatal type of brain cancer. At the last follow-up point, many of the tumor responses were ongoing, including several that had lasted for more than a year.

The high response rates to larotrectinib, combined with the long duration of those responses, suggest that the drug is “likely to be practice changing” for children whose tumors have NTRK fusions, a lead investigator on the SCOUT trial, Brian Turpin, D.O., of the University of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, said in a Loxo news release.

The experience with larotrectinib “speaks to one of the reasons for performing molecular profiling of patients’ tumors—particularly for rare cancers, where you know these translocations can occur,” Dr. von Mehren said. “Even in a small percentage of patients, you can have a significant impact with the right targeted therapy.”

Larotrectinib’s development can be a model for the development of other new targeted therapies, Dr. Drilon said. “I think there are other targets that we haven’t completely explored yet that can work across many different types of cancer.”

Next-Generation TRK Inhibitor Not Far Behind

Cancer returned in 10 of the 42 patients in these first three trials who initially responded to larotrectinib. When the research team analyzed tumor and plasma samples from these patients, they found that the tumors had developed additional NTRK mutations that affect the drug’s ability to bind to TRK fusion proteins.

Based on prior research, however, Loxo has already developed a second-generation drug that can work in tumors with these mutations.

Called Loxo-195, the drug is already being tested in a small clinical trial involving patients previously treated with a TRK-targeted drug but whose disease later progressed.