Nilotinib Can Be Discontinued in Some Patients with Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

, by NCI Staff

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a major change to the recommended use of the drug nilotinib (Tasigna®) in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

On December 22, the agency approved an update to the drug’s label that states that some patients with CML who are taking nilotinib and whose cancer has been in remission for an extended period can safely stop taking it. These patients, however, must undergo regular testing to ensure the disease has not come back.

Until now, the practice has been to give nilotinib continuously until leukemia progresses, so treatment may continue for years, decades, or even the rest of a patient’s life. While this can keep CML at bay, nilotinib does have side effects including itching and rash, nausea, diarrhea, and tiredness. It can also cost insurers more than $100,000 a year for a single patient.

To be eligible to stop nilotinib under the new labeling, patients must have taken the drug for at least 3 years, and there must be evidence that almost no cells in their blood harbor the genetic mutation that causes CML—known as a sustained molecular response.

Once nilotinib treatment is stopped, patients must be tested regularly using an FDA-authorized test to monitor for possible disease recurrence.

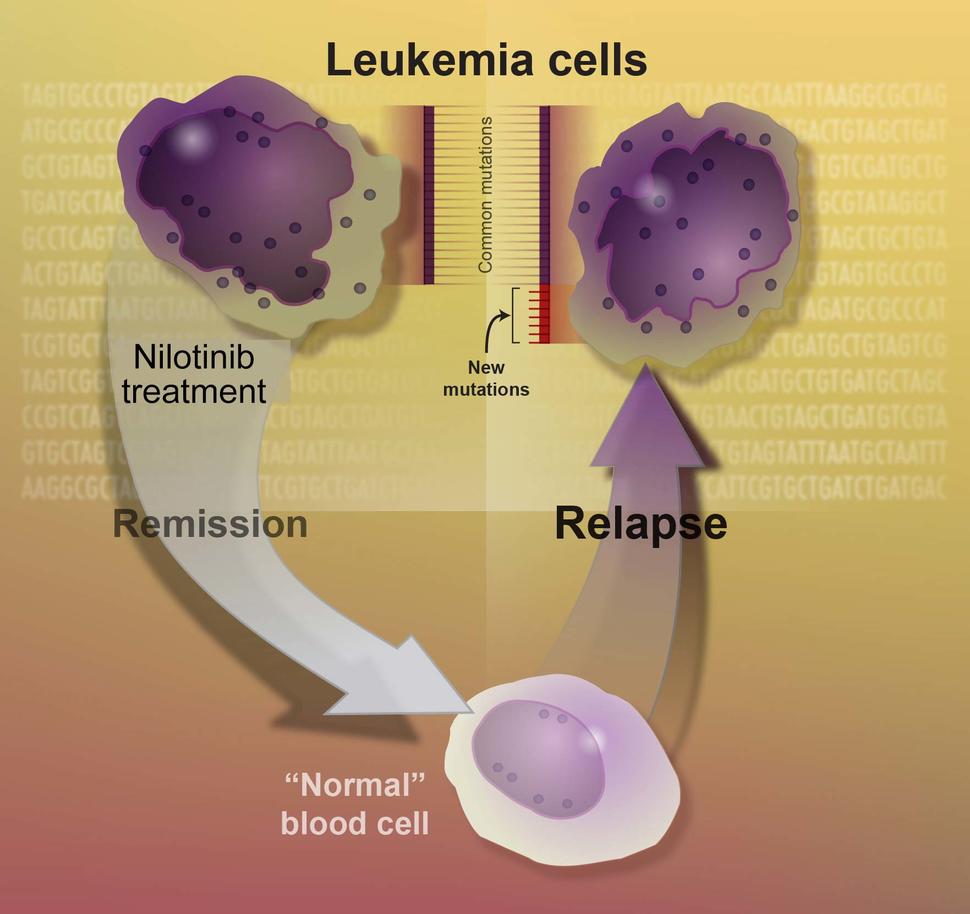

In the two clinical trials that led to the label change, almost half of the patients who stopped nilotinib experienced disease relapse. However, almost all of these patients’ leukemia went back into remission after restarting nilotinib.

Discontinuing the drug for some patients “is a safe thing to do, as long as careful monitoring is done,” commented Richard Little, M.D., of NCI's Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis.

Testing the Safety of Stopping Nilotinib

Nilotinib is a type of drug called a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI). It interferes with the protein produced by the genetic mutation that causes CML, and this interference can keep cancer cells from growing.

Patients newly diagnosed with CML are usually treated with nilotinib or one of two other TKIs, imatinib (Gleevec®) or dasatinib (Sprycel®).

FDA based the label change for nilotinib on the results of two phase 2 clinical trials, called ENESTfreedom and ENESTop.

The ENESTfreedom trial enrolled 215 patients who had taken nilotinib for at least 2 years. All trial participants continued to take the drug for one more year as part of the trial. After a year, the 190 patients still in remission discontinued the drug.

During follow-up, the participants were monitored with blood tests every 4 weeks for the first 48 weeks, every 6 weeks for the next 48 weeks, and then every 12 weeks.

After the first 48 weeks of follow-up, 98 participants who had discontinued nilotinib (52%) remained in remission. Of the remaining 91 patients, 86 restarted nilotinib after testing showed their disease had returned, and all but one of these patients went back into remission. None of the patients progressed to the deadly later stages of CML during the trial.

Early results from the ENESTop trial were very similar to the results of ENESTfreedom. The ENESTop researchers enrolled 163 patients who had taken imatinib followed by nilotinib for a total of 3 or more years.

After an additional year of nilotinib treatment during the trial, 126 participants remained in remission and discontinued the drug. Participants were monitored with blood tests every 4 weeks for the first 48 weeks.

During those 48 weeks, 73 patients (58%) remained in remission. Fifty-one patients (41%) experienced a relapse and restarted nilotinib. Of those, 50 regained a response to the drug. The one patient who did not regain a response switched to a different drug used to treat CML.

About 25% to 40% of patients in the two trials experienced muscle pain, bone pain, or both during the first 48 weeks after stopping the drug. These side effects have previously been seen in patients who stop taking nilotinib. Longer-term follow up is needed to understand whether the risk of muscle or bone pain decreases over time, wrote the ENESTfreedom study authors.

Better Responses, Safer Stopping?

An important question for future research is whether it is possible to predict whether an individual patient will maintain a molecular response after stopping nilotinib, the ENESTfreedom authors explained.

Although neither trial identified predictive factors, Dr. Little noted that doctors have a fairly good idea of which patients might safely try discontinuation: patients whose disease responds rapidly to nilotinib and who have been in remission for a long time are more likely to maintain their remission.

Conversely, patients whose leukemia took a long time to respond to nilotinib, those who needed more than one drug to generate a remission, and those who haven’t been in remission for long are riskier candidates, added Dr. Little.

This difference highlights the importance of people taking nilotinib as prescribed, stressed Dr. Little.

Nilotinib, like other TKIs used to treat CML, comes in pill form. This makes patients responsible for administering their own treatment every day, often for years on end.

“Adherence to the medication has to be quite high to achieve a molecular response,” Dr. Little said.

“Patients should start [treatment] with the idea that if they take their pills exactly as prescribed for a number of years, then the prospect of their being able to stop treatment all together is pretty high,” he continued. “But if they don’t, then the likelihood of being able to successfully stop is decreased.”

The results from these two trials, along with previous research exploring how to safely stop other TKIs, generates excitement about how CML treatment might be adjusted to get more patients’ disease to respond early and durably, said Dr. Little.

Currently, he explained, researchers are looking at whether adding other types of treatment—such as immunotherapy—to TKIs might create faster, longer-lasting remissions.

“If we can get more patients into a molecular remission and then they’re able to successfully stop [therapy], that’s going to be a tremendous benefit both to the individual patient and to the overall national health expenditures for CML,” he concluded.