Despite Proven Safety of HPV Vaccines, More Parents Have Concerns

, by Nadia Jaber

Despite more than 15 years of consistent evidence that HPV vaccines are safe and effective, a new study has found that more parents are citing concerns about the vaccines’ safety in recent years. The findings highlight an urgent need for doctors and public health leaders to address these concerns with parents, according to the scientists who led the study.

The HPV vaccine protects against six different kinds of cancer (cervical, anal, back of the throat, penile, vaginal, and vulvar) that are caused by infection with the human papillomavirus, or HPV.

The vaccine is recommended for girls and boys aged 11 or 12. Although vaccination rates have been rising since the first HPV vaccine was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2006, only 59% of 13- to 17-year-olds were fully vaccinated in 2020.

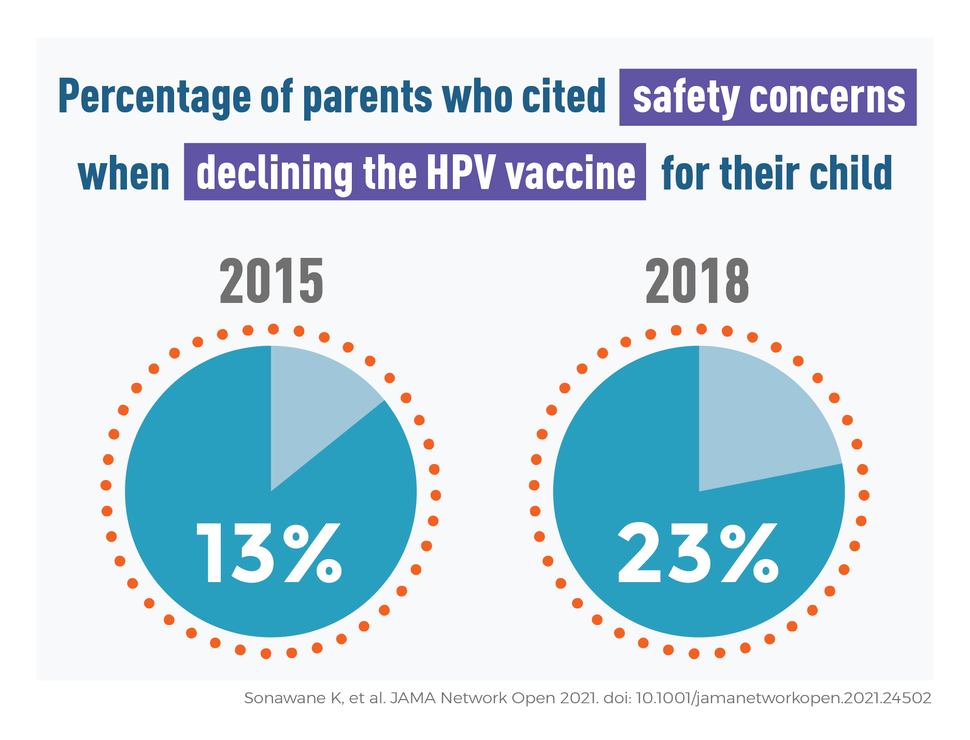

Some parents have always cited concerns about safety for declining to get the HPV vaccine for their kids. But from 2015 to 2018, the study showed, the percentage of parents who declined the HPV vaccine for their kids due to safety concerns nearly doubled. During the same time frame, reports of serious health issues after HPV vaccination were consistently rare, the study found.

Results from the study were published September 17 in JAMA Network Open.

“It was really shocking to me to see this parallel analysis of parental perceptions and statements about safety and the actual safety results, and they’re going in opposite directions," said Robin Vanderpool, Dr.P.H., chief of NCI’s Health Communication and Informatics Research Branch, who wasn’t involved in the study. "I think it’s really telling.”

“Our suspicion is that the rising safety concerns are probably being driven by [the] use of social media and people trying to find vaccine information online,” said the study’s lead researcher, Kalyani Sonawane, Ph.D., of UTHealth School of Public Health in Houston, Texas.

The study looked at data from 2015 to 2018, Dr. Vanderpool noted, well before the COVID-19 pandemic and rising hesitancy around COVID-19 vaccines. “My worry is that you’re going to have a synergy or convergence, and [HPV vaccine hesitancy] might get worse,” she said.

“The public health and cancer control communities should be thinking about how to address this potential outcome through both health communication research and public health practice,” Dr. Vanderpool added.

Fewer Health Issues after Vaccination

To look at trends in health issues reported after HPV vaccination, the researchers turned to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), a website operated by CDC and FDA. Patients, caregivers, health care professionals, and vaccine manufacturers can use VAERS to voluntarily report any health problems that occur after vaccination.

From 2015 to 2018, reports of health issues following HPV vaccination went down overall.

Reports of serious health issues after HPV vaccination were consistently rare—around 1.8 per 100,000 HPV vaccine doses, or 0.0018%. A total of 758 serious health problems that arose after HPV vaccination were reported in VAERS during that time. Meanwhile, the rate of nonserious health issues following HPV vaccination reported in VAERS dropped from 43 to 28 per 100,000 vaccine doses.

Just because a health problem is reported in VAERS doesn’t mean the vaccine caused it, Dr. Sonawane cautioned. Some health reports were hearsay and lacked sufficient information to be verified, she added.

“We have to be cautious about interpreting VAERS data and not make any cause–effect associations,” she said. According to CDC and FDA, VAERS data can only be used to find unusual patterns that should be evaluated in additional studies.

Another CDC-funded vaccine safety program, the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), also performs vaccine safety studies, including those based on reports to VAERS. A recent VSD study of the 9-valent HPV vaccine (Gardasil 9), for example, tracked new vaccinations over a 2-year period and identified no new safety issues.

More Parents Citing Safety Concerns

The researchers also looked at results from a large, CDC-led survey of parents of teens aged 13 to 17. From 2015 to 2018, more than 39,000 caregivers of teens who had not received the HPV vaccine responded to the survey and selected 1 of 31 reasons for declining the vaccine.

The top five selected reasons were:

- “Safety concerns”

- “Not recommended”

- “Lack of knowledge”

- “Not sexually active”

- “Not needed or not necessary”

In 2015, 13% of parents had cited safety concerns as the main reason for declining the HPV vaccine. But by 2018, that percentage had risen to 23%. During the same period, there was a drop in the percentage of parents citing three of the other most common reasons for declining or delaying the HPV vaccine.

HPV Vaccine Side Effects

HPV vaccines can cause pain, swelling, and redness where the shot was given, as well as headaches, tiredness, and nausea. The most common serious side effects of HPV vaccination are dizziness and fainting. There is no evidence that HPV vaccines lead to infertility or autoimmune diseases, although these are common myths.

When the researchers looked at the data by state, they found that the number of parents citing safety concerns increased in 30 states and more than doubled in California, Mississippi, South Dakota, and Hawaii.

Vaccine Misinformation on Social Media

“Why are more parents concerned now about [HPV] vaccine safety than when it was first launched or in 2015; now that over 135 million doses have been administered in the United States?” Nosayaba Osazuwa-Peters, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the Duke University School of Medicine, and his colleagues wrote in a commentary on the study.

“Studies have shown that while individuals trust medical professionals for health information, a growing number are turning to the internet for first and second opinions about HPV, HPV vaccines, and HPV-associated cancer,” they continued.

Unfortunately, some information about HPV vaccines and cancer found online and on social media is inaccurate. There has been a rise in negative and incorrect information—also called misinformation—about HPV vaccines on social media in recent years, Dr. Sonawane noted. And research has shown that parents who are exposed to misinformation about HPV vaccines on social media are less likely to vaccinate their children.

Nationwide programs, such as CDC’s “Vaccinate with Confidence” program, can help tackle vaccine misinformation and provide resources for effective communications, Dr. Sonawane said. There are also resources like smartphone apps, she added, that teach health care providers effective strategies for talking with parents about the HPV vaccine.

Changing Parents’ Minds

Even though vaccine hesitancy appears to be rising, there is a subset of people who have misgivings about vaccines but are open to changing their minds, Dr. Vanderpool noted.

Sarah Kobrin, Ph.D., M.P.H., head of NCI’s Health Systems and Interventions Research Branch, who wasn’t involved in the study, agreed.

“I don’t want to rush to the idea that the shift towards giving this reason [of safety concerns] means that fewer people will get the vaccine,” Dr. Kobrin said. “You have to look at this finding and the vaccine uptake [rates] together.” According to recent data, there has been a steady increase in HPV vaccination rates.

“I think there are people who might be saying ‘I’m concerned about safety,’ but if you had the opportunity to talk and listen to them, to educate, and to have an informed decision-making type of conversation, you might be able to move them in a direction where their safety concerns are addressed and there’s more willingness to vaccinate,” Dr. Vanderpool explained.

To change people’s minds, the key is to not be judgmental and to provide the time and space for in-depth conversations, Dr. Kobrin noted.

“You can’t tell people they’re wrong if you actually want them to hear alternative information.

If you doubt their good intentions, they’re not going to hear you out,” regardless of how sparse the evidence is for their beliefs, she said.

A better approach, Dr. Kobrin went on, would be to say, “Let’s all talk about why we believe what we believe. What is the evidence? Let’s sift it through together. We all want the same thing.”

In addition to thoughts and beliefs about a topic, people’s behavior is also influenced by “the things they see their friends and family and important people in their community recommending or doing for themselves,” she added.

NCI has funded 11 research projects to explore the influence local organizations have on community members with HPV vaccine hesitancy. Although the results are yet to be published, the studies suggest that well-respected local organizations can have a positive influence on peoples’ perceptions about HPV vaccines, Dr. Kobrin said.