Dexrazoxane Protects the Heart Long Term for Kids Being Treated for Cancer

, by Shana Spindler

Today, more than 80% of children diagnosed with cancer are alive 5 years after treatment. This is one of the biggest successes of pediatric medicine in the last 50 years. But the advances in treatment can have a cost: Some childhood cancer survivors develop life-threatening heart problems later in life, due in part to the chemotherapy that initially helped save them.

One of these heart-damaging drugs is doxorubicin (Adriamycin), which is used to treat many types of childhood and adult cancers. Results from a new study show that giving a drug called dexrazoxane (Zinecard) before each dose of doxorubicin substantially decreases the risk that childhood cancer survivors will have treatment-related heart problems in adulthood.

For younger patients, treatment-related heart damage is “an important, life-changing problem because it can impact many decades of life,” said one of the study leaders, Eric Chow, M.D., of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center. The study’s findings, he added, have immediate implications for children and teens being treated for cancer today.

The study evaluated the cardiovascular health of 195 people who had been diagnosed with cancer in childhood, about half of whom had received dexrazoxane prior to doxorubicin in clinical trials years earlier.

Almost two decades after their cancer diagnosis, study participants who had received dexrazoxane had healthier hearts than participants who had not received it.

“This has potential to be practice changing,” Dr. Chow said, noting that some doctors have been hesitant to use dexrazoxane without more definitive evidence that it provides long-term protection against heart issues.

Findings from the NCI-funded study were published January 20 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“This is a very important study,” said pediatric oncologist Nita Seibel, M.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, who was not involved in the work. “We want to make sure childhood cancer survivors have the best quality of life … and anything we can do to prevent heart disease would be beneficial.”

Dexrazoxane offers sustained heart protection two decades out

Heart disease is one of the most concerning long-term side effects from doxorubicin therapy. At least 10% of people who receive high doses of the drug during treatment for childhood cancer experience heart failure by age 40.

Adults with cancer are also at risk of cardiac injury from doxorubicin. In 1995, dexrazoxane was approved by the Food and Drug Administration to reduce the risk of doxorubicin-induced heart damage in women being treated for breast cancer.

In the early 1990s, study co-leader Steven Lipshultz, M.D., chair of the Department of Pediatrics at the University at Buffalo Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, spearheaded research showing that dexrazoxane could prevent short-term chemotherapy-induced heart damage in children with leukemia. But for years, the drug hasn’t been used widely in children being treated for cancer, Dr. Chow said, due to uncertainties about its long-term risks and benefits.

In the new study, dubbed HEART, participating hospitals in the United States and Canada recruited people who had been treated for childhood cancer at their institutions. The average age of people in the study was 29. All had participated in one of several NCI-supported Children’s Oncology Group or Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Childhood ALL Consortium clinical trials testing dexrazoxane almost 20 years earlier.

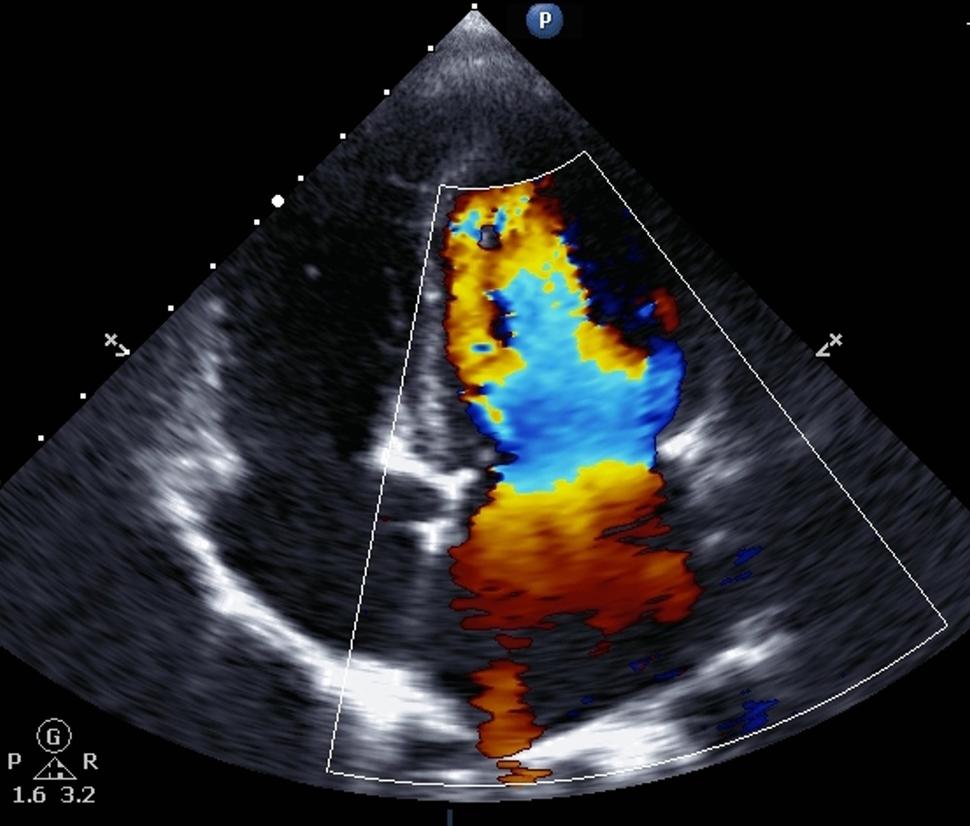

Clinicians from the hospitals where study participants were initially treated completed a one-time assessment of each participant’s heart health. That included measuring the structure and pumping strength of the heart’s left ventricle and screening for blood-based markers of heart damage and stress.

Compared with participants who had not received intravenous dexrazoxane prior to doxorubicin, those who received it had significantly better heart-pumping strength, without significant differences in the heart’s ventricular structure. They also had more normal markers of heart muscle stress.

The protection was most notable in those who had received a cumulative dose of doxorubicin greater than 250 mg/m2. This dose is considered to trigger a higher risk for heart disease, according to recently published international guidelines. Dr. Lipshultz emphasized, however, that any child treated with doxorubicin is likely at some risk for future heart problems, regardless of their cumulative dose.

“We found that, 18 years later, the protection to the heart was sustained,” Dr. Lipshultz said.

Importantly, he continued, the new results add to previously reported findings from the same study showing that giving dexrazoxane doesn’t make treatment with doxorubicin less effective against the cancer or increase the likelihood of survivors developing a second primary cancer—a concerning possibility proposed by some doctors.

This is “reassuring,” particularly to the families of children facing treatment with doxorubicin, Dr. Seibel said. “In the past, you would have to say that there is limited long-term data … [so] having longer-term data is definitely better.”

Balancing cancer cures in childhood with decades of active adult life

Doxorubicin is a type of anthracycline. This class of drugs includes many of the most effective chemotherapy drugs for childhood cancers—more than 50% of children with cancer are treated with an anthracycline. But these drugs also harm healthy cells, including heart muscle.

Dr. Lipshultz was one of the first cardiologists to recognize this problem. In the 1980s, he consulted on several cases of childhood cancer survivors who developed heart failure 10 or more years after their cancer diagnosis.

The prevailing thinking at the time was that children who didn’t show evidence of heart failure during treatment were unlikely to have future heart issues, he recalled. But after evaluating more than 100 survivors of childhood cancer who had been treated with doxorubicin, he discovered that more than 60% had unhealthy hearts. This percent, as well as the severity of heart problems for the group, increased over time.

“What we have shown in other studies is that damage occurs with even the very first dose of anthracyclines,” said Dr. Lipshultz, who believes the heart should be protected before every dose.

For 30 years, Dr. Lipshultz has argued that the treatment paradigm for children receiving doxorubicin as part of their cancer treatment needs to shift, noting that the successful treatment of childhood cancer should consider the quality of life for the cancer survivor and their family over a lifespan.

In that sense, these new findings are “so exciting,” Dr. Lipshultz said, because they show we can help prevent long-term damage to the heart from an anthracycline—an effective childhood cancer treatment with an unfortunate side effect.

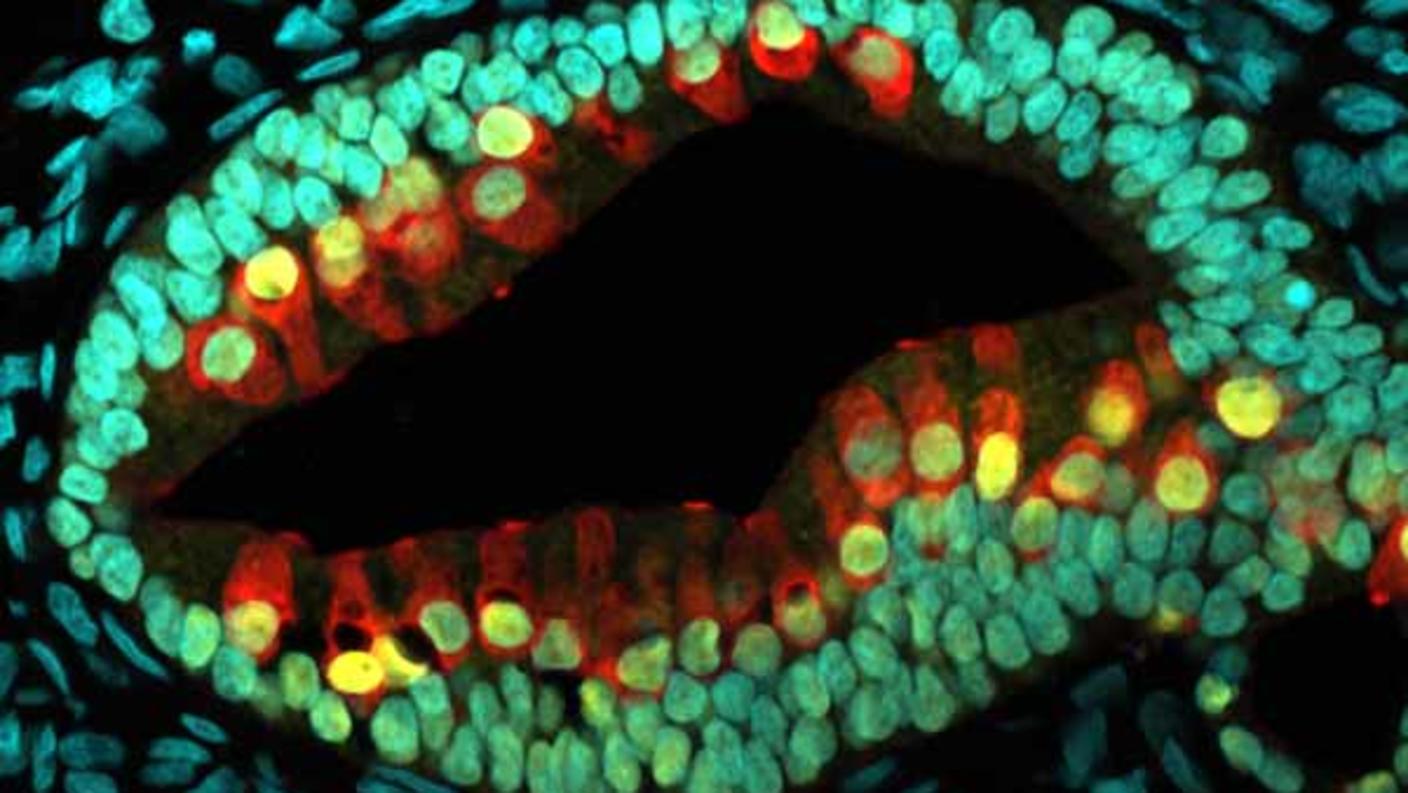

When an anthracycline enters a cell, it binds to iron, he explained. This creates free radicals that “punch holes” in heart muscle cells and irreversibly damage mitochondria, the energy factories that allow the heart muscle to squeeze with good force, Dr. Lipshultz said. This cell death and mitochondrial damage in childhood leads to an adult heart with weaker muscles, which puts more stress on the heart.

Dexrazoxane, when administered immediately before each doxorubicin infusion, counters this effect by binding up iron in the blood, he continued. In the process, less iron is available to doxorubicin, which decreases the production of free radicals.

Dr. Chow noted that there are factors to consider when using dexrazoxane in children with cancer, such as the potential for a decrease in the production of blood cells in those who are already vulnerable to illness. However, “you can’t give dexrazoxane retroactively,” he said.

Recent guidelines from international organizations recommend dexrazoxane for children receiving certain doses of anthracyclines. Already in the United States, some upcoming treatment guidelines for specific cancers are going to recommend that dexrazoxane be given with any anthracycline dose, Dr. Seibel noted.

More work to be done

The study team acknowledged that the average age of the participants was only 29 years, and clinical heart failure following treatments for childhood cancer may not appear until later. It will be important to follow these patients to see if the lower risk of heart problems becomes more prominent over even longer periods, they wrote.

Dr. Chow noted that most childhood cancer survivors today didn’t receive dexrazoxane prior to their anthracycline treatments. “But rather than despair over that fact, the most important thing for those survivors is trying to control modifiable risk factors for heart disease,” he emphasized. That includes things like maintaining a healthy weight and blood pressure, and controlling diabetes and cholesterol levels.

For now, dexrazoxane is the only heart-protective drug available to children with cancer.

However, some groups are exploring additional protective measures, Dr. Chow said, such as testing a type of anthracycline that has a special fat coating to see if it can stop it from damaging the heart. Other researchers are trying to prevent heart damage by blocking proteins required for the death of heart cells.

Moving forward, this study shows the power of collaborative research involving both oncologists and cardiologists, Dr. Chow said. As a cardiologist, Dr. Lipshultz agreed, saying that he feels privileged to study this generation of long-term survivors of childhood cancer.