FDA Authorizes Blood Test for Assessing Risk of Hereditary Cancers

, by Edward Winstead

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted marketing authorization for a blood test that detects inherited genetic changes that may increase the risk of developing certain cancers. The test is the first of its kind to be granted marketing authorization, the agency announced on September 29.

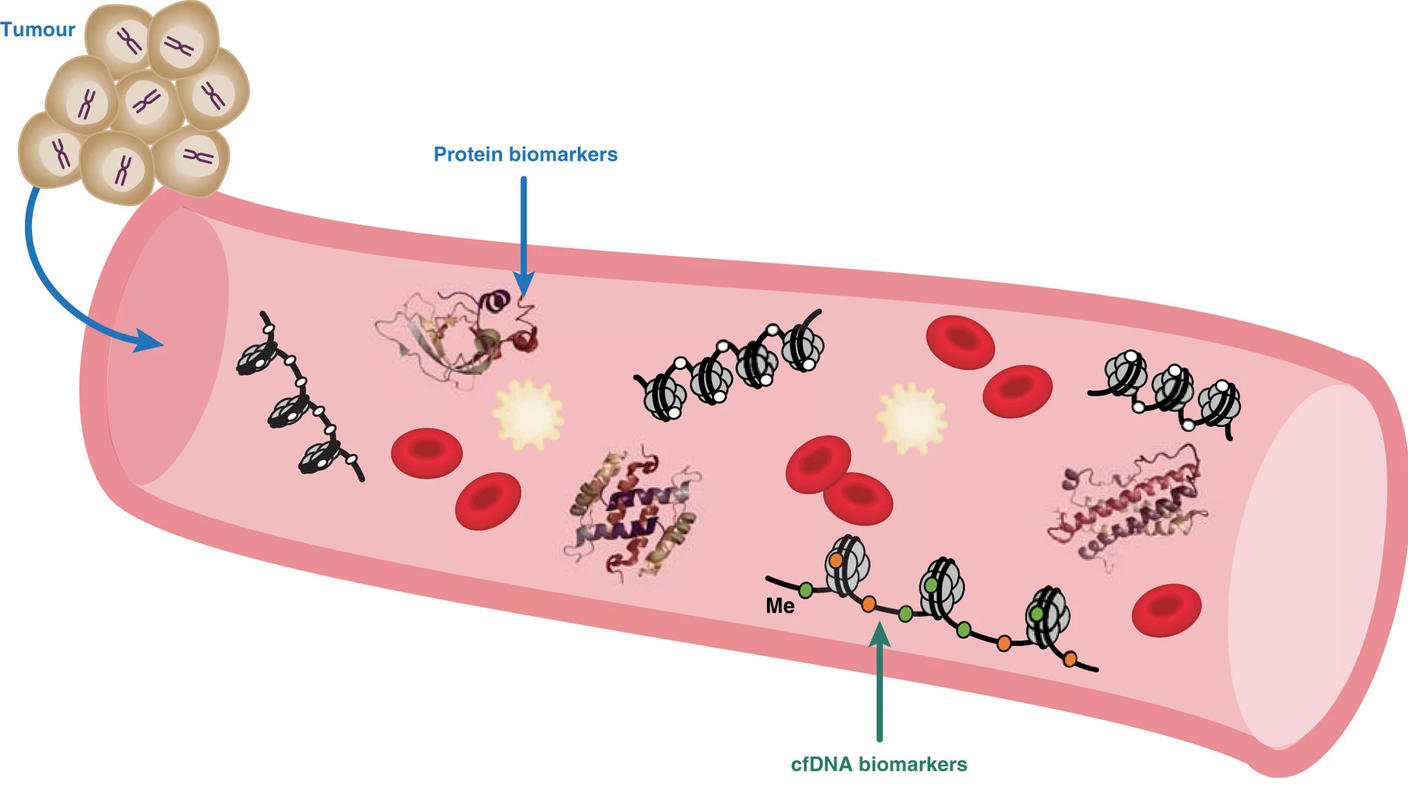

The test, the Invitae Common Hereditary Cancers Panel, analyzes a person’s blood sample for changes in 47 genes that are linked to hereditary forms of cancer. FDA described the test as “an important public health tool that can offer individuals more information about their health, including possible predisposition to certain cancers.”

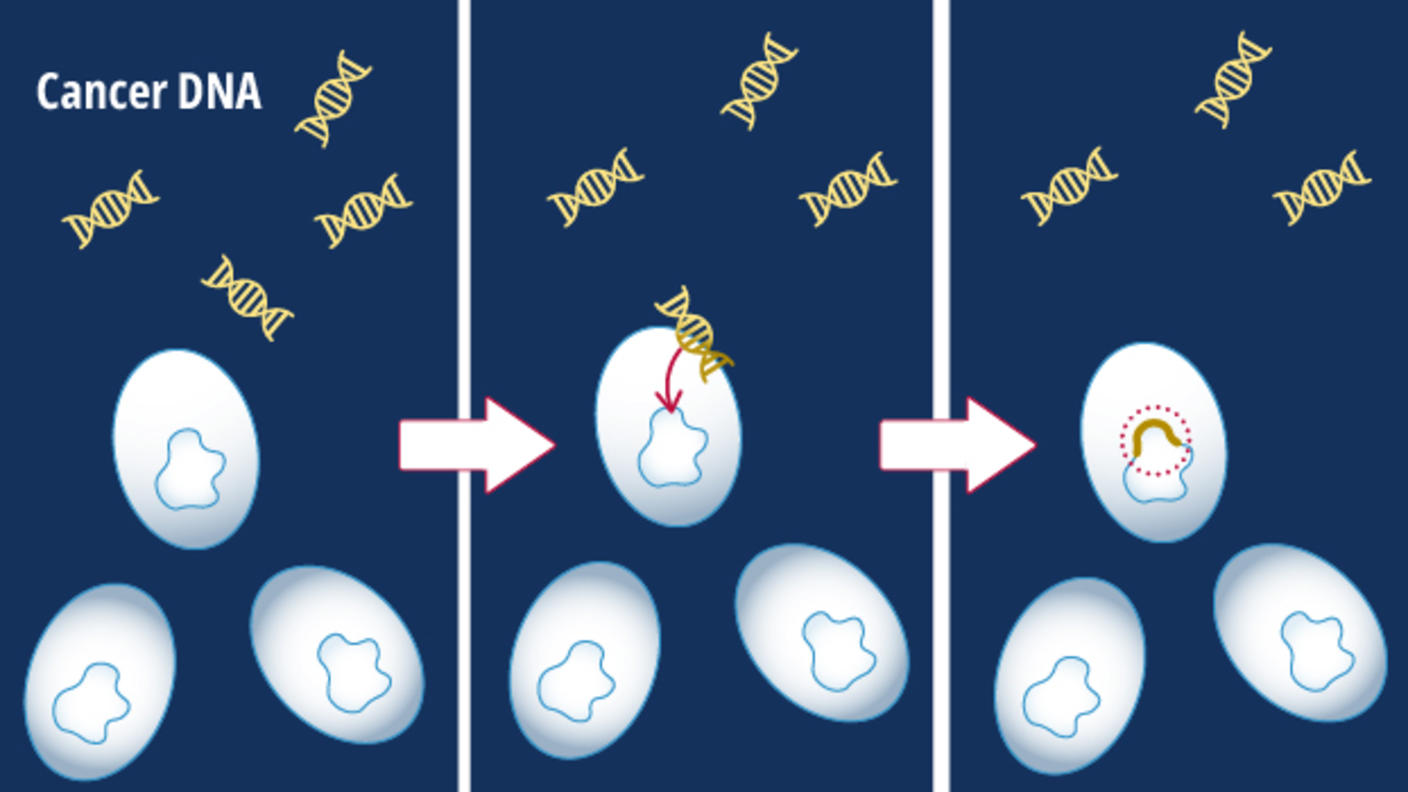

Up to 10% of cancers are thought to be caused by genetic changes that are passed from parent to child. Inheriting one of these changes does not mean that a person will develop cancer, but it increases the likelihood of the disease occurring.

Doctors can use personal and family medical histories to identify people who may have an increased risk of developing cancer. For example, people who have several relatives who have had the same type of cancer might have an increased risk of developing cancer.

For individuals suspected of having an increased risk of hereditary forms of cancer, the Invitae test can be used to confirm the presence or absence of hundreds of possible genetic changes, or variants, in the 47 target genes.

“This test is intended for people who may have an increased risk of developing cancer to better understand what that level of risk is,” said Lori Minasian, M.D., deputy director of NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention, who was not involved in the development of the test.

Individuals who are concerned about whether their family history puts them at risk for cancer should consult with a genetic counselor, Dr. Minasian added. The Invitae test is available only by prescription from a doctor.

Using genetic test results to help guide medical care

The test’s panel of 47 genes includes the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Certain DNA changes in these genes increase the risk of hereditary forms of breast and ovarian cancer as well as several additional types of cancer.

The panel also includes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2, genes that are linked to Lynch syndrome, an inherited condition that increases the risk of developing various cancers. Some people with Lynch syndrome develop colorectal cancer in their 20s, which is much earlier in life than when screening for the disease typically begins.

Many tools for assessing a person’s risk of cancer, including genetic tests, have been developed in recent decades. “This particular test is the first to have undergone FDA’s critical review to demonstrate that it is safe and effective for its intended use,” Dr. Minasian said.

To validate the test’s performance, Invitae researchers analyzed more than 9,000 samples from people known to have one of the genetic changes included in the test, achieving greater than 99% accuracy for all of the tested changes, according to the FDA.

Individuals who learn from genetic testing that they have inherited cancer-related gene variants may be able to take steps to reduce the risk of the disease and detect it early, according to Wendy Rubinstein, M.D., Ph.D., a senior scientific officer in NCI’s Division of Cancer Prevention.

“The purpose of this type of genetic testing is to create opportunities for prevention and early detection in families affected by hereditary cancers,” said Dr. Rubinstein, who was previously a deputy director in the FDA office that cleared the Invitae test.

For instance, people who have inherited harmful variants in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes may have various options for reducing their cancer risk, including starting breast cancer screening at a younger age, undergoing risk-reducing surgery, and using medications that can lower risk.

Similarly, people who have inherited genetic variants linked to Lynch syndrome may start colorectal cancer screening earlier than recommended by guidelines and/or have more frequent screening to detect early signs of colorectal cancer.

In addition to detecting inherited variants in people at risk of cancer, the test could also be used to identify variants in people who have already been diagnosed with cancer, the FDA said. Information about such variants might help inform decisions about how best to treat the disease.

A new regulatory classification

FDA announced that it had created a new regulatory classification for the Invitae test and future multigene panel tests that have the same intended uses. These tests are classified by the agency as devices and, as a result, are regulated differently than drugs.

Some users of the Invitae test might not realize that they could still have some risk of developing cancer even if they test negative, the agency cautioned. That’s because the test is not intended to evaluate all genes that are linked to an increased cancer risk, and many factors other than a person’s genetic makeup can contribute to the development of cancer.

There’s also the potential for false-positive and false-negative results, which carry their own risks. Somebody who has a false-positive result, for example, might undergo an unnecessary treatment to reduce the likelihood of a cancer diagnosis.

But, in the case of any test cleared under this regulatory classification, these risks are lessened by “the analytical performance validation, clinical validation, and appropriate labeling of this test,” according to FDA.

Revealing new variants that may be involved in cancer

Invitae’s test uses next-generation sequencing to check for changes in the 47 target genes. To interpret the test results, the company uses evidence from various sources, including information from published studies, public databases, prediction programs, and Invitae’s internal curated database of cancer-related genetic variants, explained Jim McKinney, an FDA spokesperson.

“New variants may be identified when testing patients,” Mr. McKinney said, adding that thousands of inherited variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have been identified.

The clinical significance of some newly identified variants may not be readily apparent, at least at first. But over time, researchers may learn more about these so-called variants of unknown significance and whether they might contribute to an increased risk of hereditary cancer.

“As research progresses, we can learn that a variant of unknown significance may actually have some probability of increasing the risk of cancer,” Dr. Minasian said.

She pointed to a recent study in which several participants were found to have variants of unknown significance when the research began. But as time passed, researchers learned more about the cancer risk associated with these variants, and Dr. Minasian’s team was able to share this information with the study participants.

“When we study potential risk variants, we collect information in real time,” Dr. Minasian said. “Then, as more evidence accumulates, we may discover what these variants could mean for the people who inherit them.”

The Invitae test results may include variants of unknown significance. When one of these variants is reclassified in a way that informs decisions about clinical care, the company provides the prescribing physician and the patient with an updated report, according to an Invitae spokesperson.