Olaparib after Initial Treatment Delays Ovarian Cancer Progression

, by NCI Staff

UPDATE: On December 19, 2018, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved olaparib as a maintenance therapy for some women with ovarian cancer. The approval was based on the results of the SOLO-1 phase 3 clinical trial (described below).

The approval covers the use of olaparib in women with advanced ovarian cancer with BRCA gene mutations and whose cancer has responded to the initial chemotherapy-based treatment. FDA also approved a companion diagnostic test to identify women with BRCA mutations and who are thus eligible to receive olaparib.

The drug olaparib (Lynparza) may soon be an option for some women with ovarian cancer earlier in their treatment, according to new findings from a large clinical trial. Olaparib is already approved as maintenance therapy and treatment for women with advanced ovarian cancer who have already received several lines of chemotherapy. Now, results from the SOLO-1 trial show that the drug can substantially delay the cancer from coming back after the first line of chemotherapy.

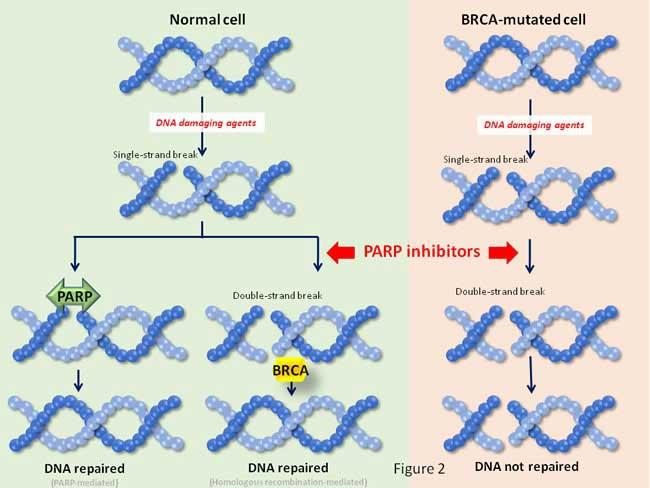

Olaparib is a PARP inhibitor, a drug that blocks proteins—called PARP—that help repair damaged DNA. Because BRCA mutations also hinder DNA repair, further inhibiting this process with olaparib can cause cancer cells that carry a BRCA mutation to die.

The SOLO-1 trial is the first phase 3 study to evaluate a PARP inhibitor as maintenance therapy in women newly diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer that harbors a mutation in the BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 genes.

Olaparib treatment led to lasting benefit for some women, and was well tolerated, reported the trial’s lead investigator, Kathleen Moore, M.D., of the Stephenson Cancer Center at the University of Oklahoma.

The researchers estimated that women who received olaparib would live a median of 3 years longer without their cancer progressing than women who received a placebo. Longer follow-up is needed to verify this estimate and to determine if olaparib helps patients live longer.

Findings from the trial were presented October 21 at the European Society for Medical Oncology 2018 Congress in Munich, Germany, and concurrently reported in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“These data would support incorporation of olaparib as part of the standard of care for women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer who harbor a BRCA mutation,” said Dr. Moore.

The findings from the SOLO-1 trial are practice changing, Isabelle Ray-Coquard, M.D., Ph.D., of Claude Bernard University in Lyon, France, said in a news release.

Maintenance Therapy for Ovarian Cancer

First-line therapy with a combination of surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy is the standard of care for women who are newly diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer. For most women, however, the cancer returns within 3 years of this initial treatment.

Bevacizumab (Avastin) is currently the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved maintenance therapy for women with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. In the NCI-sponsored trial that led to the approval, bevacizumab plus chemotherapy followed by bevacizumab alone extended median progression-free survival—that is, the time to when half of all participants lived without cancer progression—by about 6 months compared with chemotherapy alone.

The SOLO-1 trial enrolled nearly 400 women with advanced serous or endometroid ovarian, primary peritoneal, and/or fallopian tube cancer who had responded at least partially to first-line treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy. The women were randomly assigned to receive olaparib or a placebo for 2 years or until their cancer progressed. The median length of follow-up was 41 months, and the primary endpoint was progression-free survival.

The trial was funded by AstraZeneca and Merck, the pharmaceutical companies that jointly developed olaparib.

Three years after random assignment, progression-free survival was 60% in the olaparib group and 27% in the placebo group. Treatment with olaparib reduced the risk of progression or death by 70%, the investigators determined.

Median progression-free survival was about 14 months in the placebo group. Longer follow-up is needed to determine median progression-free survival in the olaparib group, but the current analysis suggests it is likely to be longer than 4 years.

Previous studies have shown that a small subset of patients whose cancer got worse with olaparib treatment did not respond to subsequent treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy. This raises questions about how the use of PARP inhibitors for up-front maintenance therapy may alter the efficacy of later treatments, explained Elise Kohn, M.D., head of Gynecologic Cancer Therapeutics in NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, who was not involved in the study.

But 3 years after random assignment, fewer women in the olaparib group than the placebo group had cancer progression after their next round of treatment (25% versus 40%). This suggests that olaparib treatment did not diminish the potential benefit from additional therapies, Dr. Moore explained.

The FDA has given priority review to the new drug application for olaparib as maintenance therapy for women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer with a BRCA mutation.

Safety Concerns for Olaparib

The safety profile of olaparib was similar to that observed in other clinical trials.

Most side effects of olaparib were low grade, with anemia and neutropenia being the most common. Only 12% of study participants discontinued olaparib treatment because of side effects. And 2 years after the start of the trial, the change in quality of life was not substantially different between the treatment groups.

However, three women (1%) developed acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a type of blood cancer, after stopping olaparib. A similar frequency of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and/or AML has been observed in other clinical trials of olaparib.

In its previous approval of olaparib, FDA recommended that doctors monitor blood cell levels in patients who are being treated with olaparib—especially those who have ovarian cancer and inherited BRCA mutations—to watch for the development of MDS or AML.

Searching for the Optimal Treatment

While these findings show that olaparib maintenance therapy has clear benefit for women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer, questions remain.

For example, said Dr. Kohn, there is a question of “applicability [of the study results] to the general ovarian cancer population” because some women don’t respond to initial treatment as well as the study group did—most of whom had a complete response.

In addition, she said, “since olaparib and other PARP inhibitors have several approved indications already, the key question is: When is it best to use these agents?” Olaparib as well as two other PARP inhibitors—niraparib (Zejula) and rucaparib (Rubraca)—are approved as maintenance therapy for women with recurrent ovarian cancer, regardless of whether they have BRCA mutations.

Likewise, Dr. Ray-Coquard questioned whether olaparib should be combined with bevacizumab for maintenance therapy of newly diagnosed ovarian cancer.

A better understanding of the effects olaparib has on patients’ overall survival and resistance to other therapies will be critical moving forward, Dr. Kohn noted.

Gauging Sensitivity to PARP Inhibitors

Another remaining unknown is whether olaparib maintenance therapy may benefit women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer that lacks a BRCA mutation. Results from other studies of olaparib and other PARP inhibitors provide some insight.

In addition to BRCA, “there are other genes that may be mutated in ovarian cancer that make tumors susceptible to olaparib,” explained Dr. Kohn. Much like BRCA mutations, these other gene mutations cripple the DNA repair process. Genetic tests that analyze whether tumors have DNA repair deficiencies can help identify people who are more likely to respond to PARP inhibitors, she added.

A 2016 clinical trial showed that maintenance therapy with the PARP inhibitor niraparib provided some benefit to women with recurrent ovarian cancer regardless of whether they had BRCA mutations. However, women who had BRCA mutations or other DNA repair deficiencies had longer progression-free survival than those who lacked them.

In an ongoing trial, researchers are studying niraparib as maintenance therapy for women with advanced ovarian cancer following initial chemotherapy. Because BRCA mutations and/or other DNA repair deficiencies were not required for enrollment, this trial may help answer whether maintenance therapy with a PARP inhibitor might benefit women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer that lacks a BRCA mutation, Dr. Kohn said.