For Some Kids with Brain Cancer, Targeted Therapy Is Better than Chemo

, by Nadia Jaber

UPDATE: On March 16, 2023, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the combination of dabrafenib (Tafinlar) and trametinib (Mekinist) for the treatment of some children with low-grade glioma.

Under the approval, a child’s tumor must have a specific genetic mutation called BRAF V600, and their tumors either can’t be removed surgically or must have come back after previous treatment. The approval also covers new liquid formulations of both drugs, intended for use by patients who can’t take pills.

The approval was based on the results of a phase 2 clinical trial discussed in the story below.

Some children with a type of brain cancer called low-grade glioma may have a new standard treatment, according to the results of a new clinical trial. In the study, the combination of dabrafenib (Tafinlar) and trametinib (Mekinist) was safer and better than standard chemotherapy at shrinking tumors and keeping them at bay.

All of the children in the study had a genetic mutation known as BRAF V600 in their cancer cells. They also all had cancer that couldn’t be removed by surgery or that had come back after surgery.

Dabrafenib and trametinib are targeted therapies: treatments that attack cancer cells with a specific gene or protein change. Dabrafenib targets cells with certain BRAF mutations and prevents the altered BRAF protein from sending growth signals. Trametinib blocks the activity of proteins that help send these signals.

There was a “striking and significant difference” in the outcomes of patients treated with targeted therapy and those treated with chemotherapy, said the study’s lead researcher, Eric Bouffet, M.D., of The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada.

The targeted therapy combination shrank more patient’s tumors and kept tumors at bay for nearly three times longer. Children treated with the targeted therapies also experienced fewer side effects, including severe side effects. Dr. Bouffet presented the findings of the randomized phase 2 trial on June 6 at the 2022 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting.

“The results of this study are quite impressive and exciting for several reasons,” said Melissa Hudson, M.D., a pediatric glioma expert from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital who was not involved in the study.

One reason is that low-grade gliomas are the most common brain tumors in kids, Dr. Hudson said during a presentation of the findings at the ASCO meeting. And because of where gliomas grow in the brain, they often can’t be removed by surgery. In addition, chemotherapy causes health problems later in life for many children, she explained.

So, it’s very exciting to have a targeted treatment that is safer and more effective than chemotherapy, Dr. Hudson said.

Low-grade glioma

Gliomas are tumors that grow in the brain or spinal cord. When a child is diagnosed with glioma, the tumor is given a “grade.” Low-grade gliomas tend to grow and spread more slowly than high-grade gliomas.

Chemotherapy and radiation are the standard treatments for children with low-grade glioma that can’t be removed by surgery or that comes back after surgery. While the vast majority (85% to 96%) of kids with low-grade glioma survive 10 or more years after being diagnosed, they may suffer from harsh long-term side effects of the treatment, such as nerve damage, endocrine disorders, learning disabilities, and infertility.

“It’s important to try to identify treatments that minimize the long-term treatment-related late effects in survivors” of low-grade glioma, said Malcolm Smith, M.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, who was not involved in the study.

Recent discoveries about the biology of gliomas have led to some new treatment ideas. In particular, studies have found that 15% to 20% of children with low-grade glioma have a BRAF V600 mutation in their tumors, leading to clinical trials of targeted therapies that block BRAF or proteins it works with.

In 2019, Dr. Bouffet and his colleagues found that dabrafenib shrank the tumors of some children with low-grade glioma. Around the same time, large clinical trials showed that for adults with skin, thyroid, and lung cancer that had BRAF V600 mutations, adding trametinib to dabrafenib was far more effective than dabrafenib alone.

So, Dr. Bouffet and his colleagues tested the combination in a small clinical trial of children with low-grade glioma, finding that the treatment was safe.

That then led to this larger trial, the “first ever randomized clinical trial of targeted treatment versus chemotherapy in [pediatric] patients with low-grade glioma,” Dr. Bouffet noted.

Testing dabrafenib plus trametinib

More than 100 children with low-grade glioma, ages 1 to 17, were involved in the study. Novartis, the manufacturer of dabrafenib and trametinib, funded the study.

The participants were randomly assigned to receive either dabrafenib and trametinib or the chemotherapy drugs carboplatin and vincristine.

If a participant’s cancer got worse while taking chemotherapy, they had the option of switching to the targeted therapy combination, Dr. Bouffet explained.

Both targeted therapies are typically taken as pills, but for this study a new liquid form was used, making it much easier for younger children to take the medicines, Dr. Bouffet said.

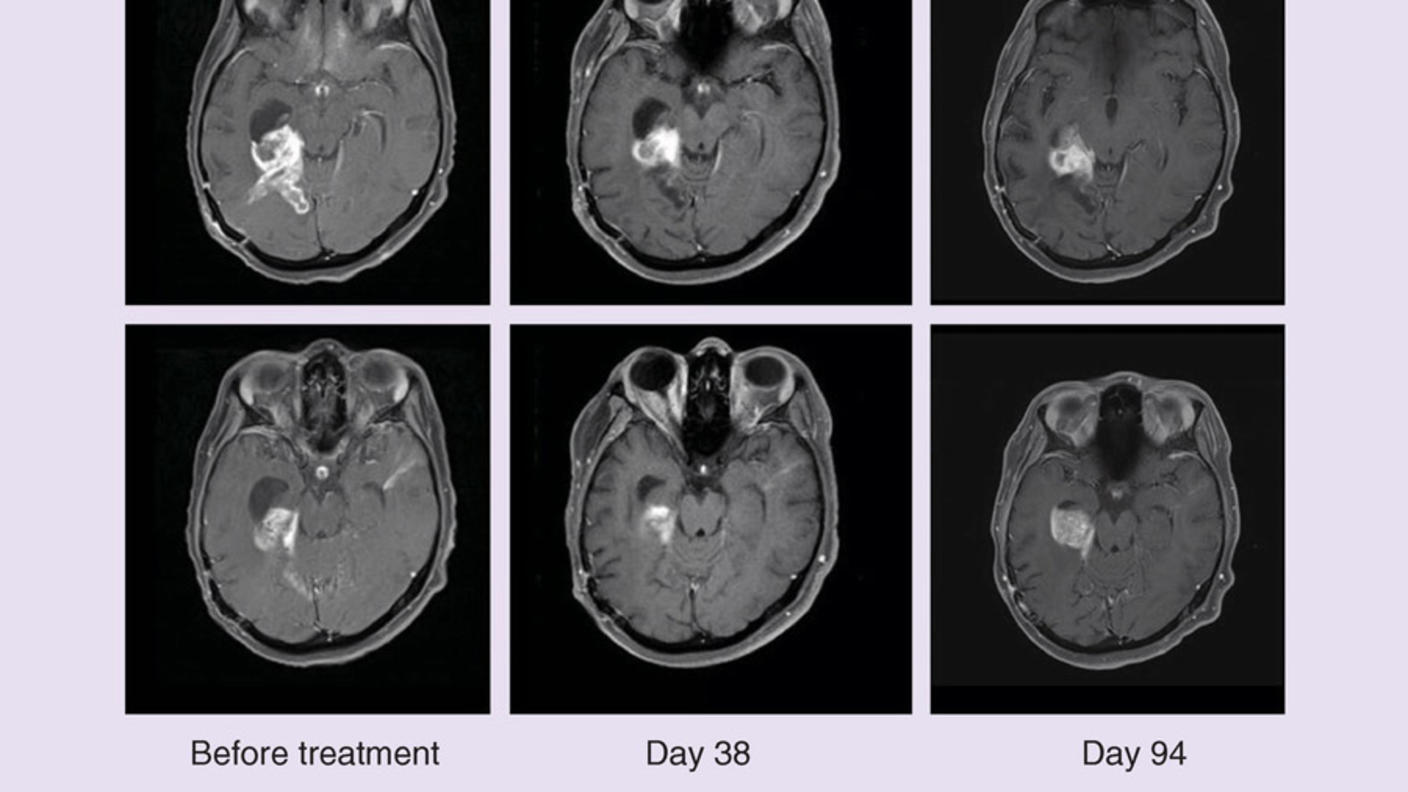

Tumors responded—meaning they shrank or disappeared completely—in 47% of patients in the targeted therapy group and just 11% of those in the chemotherapy group. The targeted therapy combination also kept patients’ tumors at bay for longer: a median of 20 months versus 7 months among children in the chemotherapy group.

Safer than chemotherapy

Among patients taking dabrafenib and trametinib, the most common side effects were fever, headache, and vomiting. Dr. Bouffet described these side effects as “manageable.”

Fewer patients in the targeted therapy group than in the chemotherapy group had a serious side effect (47% versus 94%) or stopped treatment due to side effects (4% versus 18%).

The research team is continuing to monitor the long-term safety of the targeted therapy treatment, Dr. Bouffet noted.

“Targeted therapies like dabrafenib and trametinib have the potential for reducing the long-term effects of treatment, but children who have received dabrafenib and trametinib need to be monitored for years to confirm that this is the case,” said Dr. Smith.

Dr. Hudson said she is hopeful that the targeted therapy approach will turn out to be safer in the long run.

“This type of targeted therapy will enable us to personalize treatment for these children and hopefully improve the quality of their survival long term,” she said.

Only for tumors with BRAF mutations

“It’s very important to note that this is not a treatment for all patients with low-grade glioma,” Dr. Bouffet emphasized. It only applies to children with a BRAF V600 mutation in their tumor.

A type of genetic testing known as biomarker or molecular testing can reveal if a BRAF mutation is present in a patient’s glioma.

This study demonstrates how important it is for children with low-grade glioma to get biomarker testing as soon as possible after being diagnosed, Dr. Bouffet said.

In March, NCI launched the Molecular Characterization Initiative, a program that offers biomarker testing to young patients with central nervous system tumors, including glioma. Testing is available to patients getting care at a hospital affiliated with the Children’s Oncology Group. For more information, visit the Molecular Characterization Initiative’s website.