With FDA Approval for Advanced Lymphoma, Second CAR T-Cell Therapy Moves to the Clinic

, by NCI Staff

Just a month after approving the first cancer therapy that uses genetically engineered immune cells collected from patients, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has now cleared a second such therapy.

The approval, announced October 18, covers the use of axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta™) for patients with large-B-cell lymphomas whose cancer has progressed after receiving at least two prior treatment regimens. Large B-cell lymphomas include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), the most common type; primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma; high-grade B-cell lymphoma; and transformed follicular lymphoma.

Axicabtagene, a form of immunotherapy called CAR T-cell therapy, was initially developed at NCI by Steven Rosenberg, M.D., Ph.D., of the Surgery Branch in NCI’s Center for Cancer Research (CCR), and his colleagues. It was later licensed to a private company, Kite Pharma, for further development and commercialization.

The clearance of the first CAR T-cell therapy—tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah™)—for some children and adults with advanced leukemia, was hailed as a watershed event for both patient care and cancer research.

The strong patient responses to axicabtagene in clinical trials, combined with the new approval from FDA, has further heightened the optimism for CAR T-cell therapy.

“In terms of cancer care, this is revolutionary,” said Michael Bishop, M.D., who directs the Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Program at UChicago Medicine, in a news release. “This is going to change how we treat hematologic malignancies.”

The rapid translation from the therapy’s initial development at NCI to an FDA approval “is an important accomplishment,” said CCR’s James Kochenderfer, M.D., a lead investigator on the early NCI trials. “This is a great example of how NIH partnerships with industry can work.”

Decades of Research Lead to CAR T-Cell Therapy Approvals

The most widely used type of immunotherapy is a class of drugs known as immune checkpoint inhibitors, which have been approved by FDA for the treatment of a variety of solid and blood cancers.

CAR T cells, however, are unlike checkpoint inhibitors—or any other approved cancer therapy.

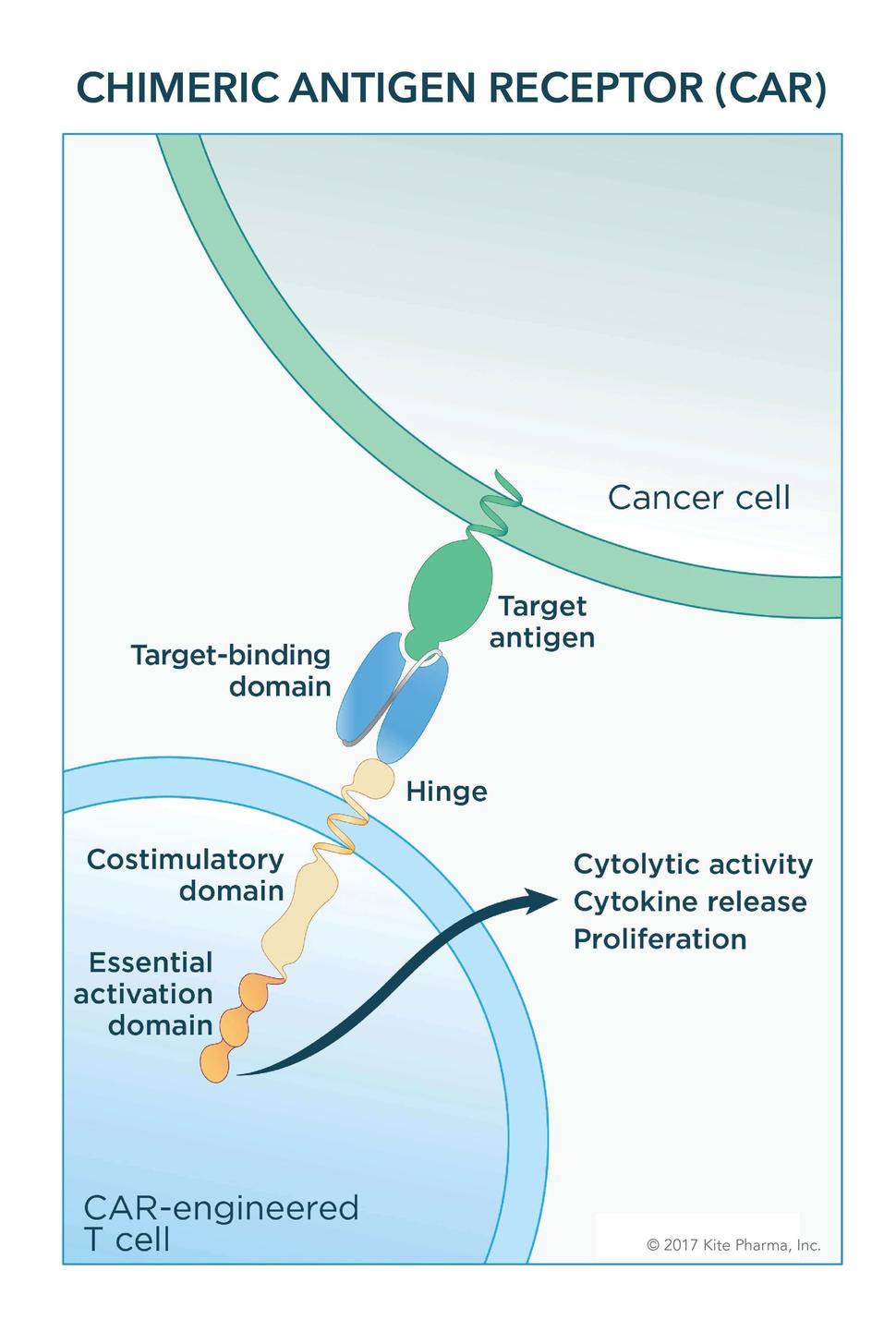

Given as a one-time treatment, the therapy uses a patient's own immune system cells. After collecting blood from the patient, T cells—the primary killing cells of the immune system—are separated out and engineered to express a special type of receptor, a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR. Finally, the engineered T cells are grown to massive numbers in the lab and then infused into the patient.

Led by Dr. Rosenberg, researchers at NCI have been working on genetically engineering immune cells as a potential cancer treatment for nearly three decades. Many of the first human clinical trials testing CAR T cells and similar cell-based immunotherapy treatments—generically referred to as adoptive cell transfer—were performed at NCI.

The initial form of axicabtagene was developed at NCI in the mid- to late-2000s. Axicabtagene, similar to tisagenlecleucel, targets the CD19 protein, which is often overexpressed on cancerous B cells. Components of the engineered receptor on the T cells help to promote the immune cells’ ability to kill cancer cells and to expand further in the body.

After CD19-targeted CARs showed promise in early-phase clinical trials conducted at NCI, the institute licensed the therapy to Kite Pharmaceuticals as part of a broader research agreement with the company to advance the development of cellular immunotherapies.

Kite, which funded the clinical trials that formed the basis for axicabtagene’s approval, was recently purchased by Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Sustained Complete Responses with Axicabtagene

More than 100 patients with large B-cell lymphomas were enrolled in the trial that led to the approval, called ZUMA-1. All patients in the trial had advanced disease that was progressing after they had received at least two previous treatments. Approximately 20% of the patients had already undergone a stem cell transplant.

Approximately half of the patients had a complete response to the treatment—that is, their cancer disappeared completely. And nearly 30% of patients had a partial response, some reduction in the extent of their disease.

For patients who initially had a complete response, the effect appears to be lasting, with the most recent data indicating that most continue to have no evidence of their cancer for at least 6 months. For many of the patients who had partial responses, however, the effects of the treatment tended to wane by the 6-month mark.

The strong patient responses seen in the trial, along with those from smaller trials performed at NCI, show that, with CAR T-cell therapy, “sustained complete responses are quite possible in lymphoma,” Dr. Kochenderfer said.

According to Gilead, longer-term data from the trial will be presented in December at a research conference.

The most common side effects in patients in the trial were low levels of white blood cells called neutrophils (neutropenia) and red blood cells (anemia). With CAR T-cell therapy, however, the most concerning side effects are cytokine release syndrome (CRS)—which, if not quickly controlled, can be fatal—and neurologic problems, such as memory loss, seizures, and confusion.

Nearly 30% of patients experienced a serious neurological event and 13% had a potentially dangerous CRS. There were three treatment-related deaths among patients in the trial.

Axicabtagene has a “black box” warning about the risks of CRS and neurological effects. FDA is requiring staff at hospitals that want to be able to offer axicabtagene to undergo special training and certification.

Given the “potential for severe side effects, having a specialized team that knows how to recognize, treat, and try to predict these toxicities is essential for administering this therapy,” said Julie Vose, M.D., chief of Hematology/Oncology at Nebraska Medicine.

Initially, Small Patient Group Eligible for Axicabtagene

Initially, according to Kite and Gilead, only an estimated 7,500 patients with DLBCL will be eligible for the treatment each year.

Given that fact, some lymphoma experts sounded notes of caution about overstating what this approval means for patients right now.

“I expect MDs to spend much more time explaining to #lymphoma patients why they are not CAR-T candidates than managing the very few who are,” John Leonard, M.D., of Weill Cornell Medicine and New York-Presbyterian Hospital in New York, wrote on Twitter.

Dr. Vose is hopeful, however, that eventually the therapy will become a more broadly applicable treatment option.

“Although it is only a small number of patients who meet the current criteria [for axicabtagene],” she said, “there will soon be additional clinical trials that will likely expand the number of patients who are eligible for this therapy.”

Following the tisagenlecleucel approval, concerns were raised by patient groups and clinicians about its cost, which was set by its manufacturer, Novartis, at $475,000. Working with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, however, the company established a performance-based model for reimbursement: Patients will only pay for the treatment if they have a response within one month of receiving it.

Gilead announced that the cost of axicabtagene will be $373,000. However, the company will not implement the same performance-based payment model as Novartis.

The treatment’s expense must be taken into careful consideration, Dr. Vose said, and “will necessitate very careful use of the therapy for only the most appropriate patients.”

Not Just a Niche Treatment for Lymphoma

Enhancements continue to be made to CAR T-cell therapies, namely to improve how well they work and to make them safer, Dr. Kochenderfer said.

In the first small group of patients with advanced lymphoma being treated as part of an NCI trial of a new CD19 CAR T cell, he noted, the early results suggest that the treatment may indeed have a lower risk of serious side effects. He stressed, however, that more work and more patients must still be treated before anything concrete can be said about the therapy’s safety.

Based on the available evidence, Dr. Kochenderfer said, there’s also a strong rationale to test CAR T cells earlier in the disease course of patients with lymphoma.

CAR T-cell therapy “is not just a blip on the radar,” he added. “It will be a critical part of lymphoma therapy for a long time.”