FDA Approves Entrectinib Based on Tumor Genetics Rather Than Cancer Type

, by Nadia Jaber

UPDATE: On October 20, 2023, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved entrectinib (Rozlytrek) to treat solid tumors in children as young as 1 month old. FDA had approved the drug in 2019 for people age 12 or older.

Entrectinib is approved to treat solid tumors in which a gene called NTRK is fused with another gene. People receiving entrectinib must have cancer that has spread or cannot be removed by surgery, and they must have already had standard treatment.

FDA based the accelerated approval on the number of children whose tumors shrank (a measure called response rate) following entrectinib treatment in two small clinical trials. Of 33 children treated with the drug, 70% had their tumors shrink, and more than half of the responses last more than 25 months.

As part of this expanded approval, FDA also approved a reformulation of entrectinib in pellet form, which can be added to soft food to make it easier to give to children and others who are unable to take capsules. The instructions for using entrectinib (the package insert) also now include information on how to dissolve the contents of entrectinib capsules in liquid so the drug is easier to take.

On August 15, 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted accelerated approval to entrectinib (Rozlytrek) for adults and adolescents aged 12 or older who have solid tumors that harbor a specific genetic alteration.

This is the third cancer drug that has been approved for a “tissue agnostic” indication, meaning for tumors with a specific genetic feature rather than a certain type of tumor.

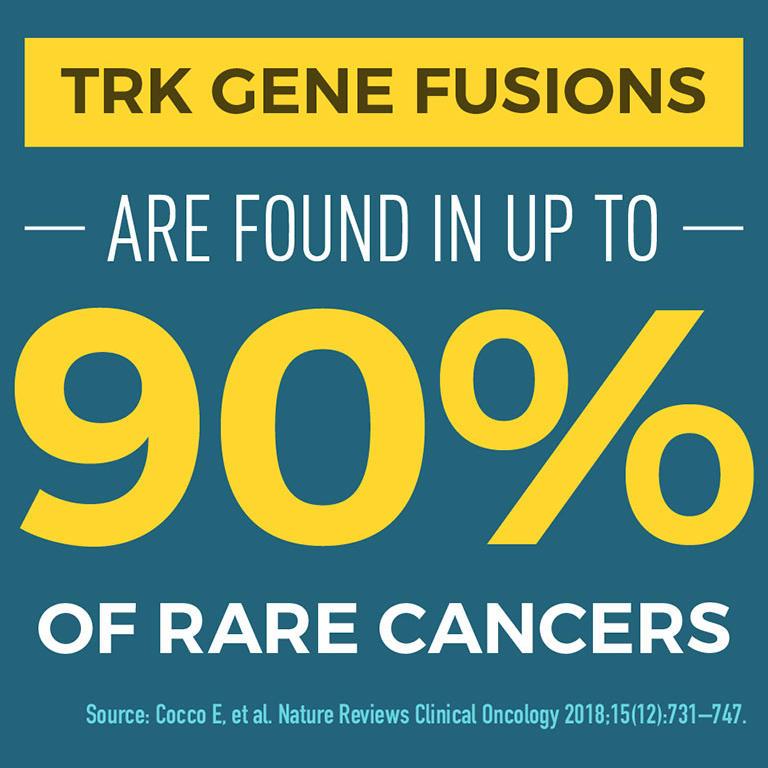

In the case of entrectinib, patients must have an alteration that causes one of the three NTRK genes to fuse with another gene, leading to the production of TRK fusion proteins. Entrectinib is a targeted therapy that blocks the activity of TRK and other proteins that can drive cancer growth.

The approval covers the use of entrectinib in people with either metastatic cancer that has gotten worse after receiving systemic treatment or locally advanced cancer that cannot be surgically removed. In addition, patients must have no other effective treatment options available.

Entrectinib is the second drug approved by FDA for the treatment of cancers with NTRK fusions. The first, called larotrectinib (Vitrakvi), was approved by the agency in November 2018.

“It’s great that another agent that is tissue agnostic has been approved, because that broadens the availability of different drugs for physicians to treat patients with these fusions,” said Nita Seibel, M.D., head of Pediatric Solid Tumor Therapeutics in NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program.

“I don’t think we’re going to get rid of tissue-specific therapies any time soon, but we’re going to see more and more of these tissue agnostic therapies in the future,” said David Hong, M.D., who leads phase 1 trials of new cancer therapies at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Dr. Hong led the early clinical studies of larotrectinib.

Also on August 15, FDA approved entrectinib for adults with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) that has a gene fusion involving the ROS1 gene. Entrectinib also blocks the activity of ROS1 proteins.

Solid Tumors with NTRK Fusions

The approval of entrectinib for solid tumors with NTRK gene fusions was based in part on results from three small clinical trials: ALKA-372-001, STARTRK-1, and STARTRK-2. The trials were sponsored by Hoffmann-La Roche, the manufacturer of entrectinib.

Trial participants had different types of cancer—mostly sarcoma, lung cancer, and salivary gland cancer—that was either metastatic or locally advanced. NTRK gene fusions were identified by a genetic test.

Among the 54 trial participants with NTRK fusions who were included in the analysis, 31 (57%) saw their tumors shrink, including four whose tumors were totally eliminated (a complete response). Among the participants whose tumors shrank, 61% had responses that lasted 9 months or longer.

Entrectinib was also tested in a fourth trial, called STARTRK-NG, that included 30 children with fusions involving NTRK, ROS1, or another gene called ALK. Most of the children had neuroblastoma, brain and spinal cord tumors, or sarcoma.

Early study findings showed that “entrectinib produced striking, rapid, and durable responses,” the trial investigators reported earlier this year. The treatment shrank tumors in several children with brain and spinal cord tumors, they noted.

These findings “look very promising,” said Dr. Seibel. “Anytime we see activity with brain and spinal cord tumors we get excited” because there are very few treatment options for such patients, she added.

Data on how well the treatment worked in children did not contribute to the agency’s approval, however.

Under an accelerated approval, the drug manufacturer must further study and verify a treatment’s clinical benefit.

NSCLC with ROS1 Alterations

The approval of entrectinib for people with NSCLC harboring ROS1 gene fusions was also based on results from the ALKA-372-001, STARTRK-1, and STARTRK-2 trials.

Among participants with NSCLC harboring ROS1 fusions, entrectinib shrank the tumors of 40 out of 51 (78%) people, including 3 people who had complete responses. For more than half of the people whose tumors shrank, the response lasted for at least 12 months.

At the beginning of the studies, seven people with NSCLC harboring ROS1 fusions were found to have tumors that had spread to their brain or spinal cord, and entrectinib shrank these metastatic tumors in five people.

Although people with brain metastases have often been excluded from clinical trials in the past, new guidelines aim to change that.

People with ROS1 fusion–bearing NSCLC often develop metastatic tumors in the brain or spinal cord, Dr. Hong noted. Though radiation can sometimes shrink such tumors, treatments like targeted therapies and chemotherapy often don’t work, he added.

Side Effects Include Heart Failure, Cognitive Effects

The most serious side effects seen in the four clinical trials, as well as in other studies of entrectinib, were congestive heart failure, central nervous system effects (such as cognitive impairment and dizziness), and bone fractures. The most common side effects were fatigue, constipation, and a distorted sense of taste (dysgeusia).

Children who received entrectinib were more likely than adults to experience certain adverse effects like neutropenia, bone fractures, and weight gain.

Effects on the central nervous system—especially dizziness—are expected from drugs that target NTRK, Dr. Hong explained, because TRK proteins play important roles in the development and functions of the nervous system.

“Over time, patients can acclimate themselves and [those symptoms will] improve, but in a very small subset of patients, it can be a significant problem,” he said.

Overall, about 3% of patients experienced congestive heart failure, which, in most cases, resolved after entrectinib was paused or stopped and the patient was given other medicines to treat heart failure.

Unlike larotrectinib—which did not appear to cause congestive heart failure—entrectinib targets multiple proteins. “I suspect that’s why it can cause heart failure,” Dr. Hong said.

A Choice of Treatment

The approval of entrectinib provides an additional treatment option for patients with advanced cancer, potentially creating the opportunity for patients and their doctors to choose between different therapies.

For example, some adults and children with cancers that have an NTRK fusion are also eligible for treatment with larotrectinib.

For children, the choice between entrectinib and larotrectinib may come down to the patient’s age and what type of cancer they have, Dr. Seibel said. Larotrectinib is available in a liquid formulation that is approved for children who are younger than 12 years old, she pointed out, whereas entrectinib is not. On the other hand, entrectinib may be effective for children with brain tumors, while larotrectinib’s efficacy for brain tumors and brain metastases is currently being evaluated. The two drugs also have different side effect profiles, Dr. Seibel added.

And for people with NSCLC harboring a ROS1 fusion, the only other targeted therapy option approved by the FDA is crizotinib (Xalkori).

Finding Rare Genetic Alterations

Gene fusions involving the NTRK and ROS1 genes are found in around 1% of people with solid tumors and NSCLC, respectively. But for some specific tumor types, like mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (a rare salivary gland cancer) and infantile fibrosarcoma, the prevalence of NTRK fusions is nearly 100%, Dr. Hong noted.

The gold standard for finding these fusions is a type of genetic test called next-generation sequencing.

“This approval, and the approval of larotrectinib, emphasize the need for next-generation sequencing profiling of patients’ tumors, particularly metastatic cancer patients,” Dr. Hong said, because sequencing can sometimes identify potential treatment options. Although more people with metastatic cancer are getting these tests than ever before, it’s nowhere near 100%, he added.

Yet some health care facilities are incorporating these tests into the standard procedure for people who are being diagnosed with cancer, Dr. Seibel pointed out.

“If we screen [patients] when they are first diagnosed, it may even turn out that [these gene fusions] are a bit more frequent than we think,” she added.